New Mexico Skunks: Identification, Ecology, and Damage Management

Guide L-214

Samuel T. Smallidge

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Extension Wildlife Specialist, Department of Extension Animal Sciences and Natural Resources, New Mexico State University. (Print Friendly PDF)

Introduction

Skunks are common throughout most of North and South America. They are omnivores that eat insects, rodents, other animals, and a variety of plants. Although skunks can be beneficial to humans by eating insects and rodents, they are better known for behaviors such as damaging lawns, denning under buildings, spraying pets, eating poultry and eggs, and carrying diseases communicable to humans and pets. Skunks were once classified as members of the weasel family (Mustelidae), but are now recognized as belonging to their own family (Mephitidae). The conspicuous coloration of skunks serves as a warning to would-be predators to avoid them or suffer the consequences of being sprayed with a concentrated musk.

Different species of skunks are adapted to live in a variety of habitats, from coastal plains to high mountains, as well as urban environments. New Mexico’s diversity of habitats provides suitable conditions for four species of North American skunks: the striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), western spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis), hog-nosed skunk (Conepatus leuconotus), and hooded skunk (Mephitis macroura). Although known to occur in New Mexico, hog-nosed and hooded skunks are less commonly seen. While the distribution of these skunks varies within the state, they all have characteristics that make them unquestionably identifiable as skunks. Skunks are not protected furbearers in New Mexico.

(Photo of stripped skunk by Bryan Padron, Unsplash.com.)

Identification

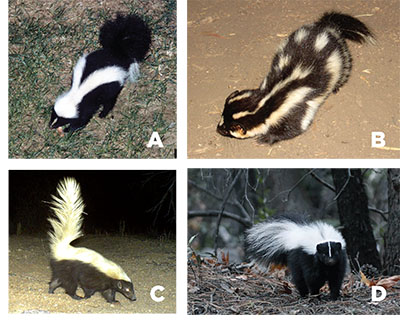

The most common skunk in New Mexico is the striped skunk. Their jet-black fur is marked by prominent, longitudinal white stripes that run from the neck along the length of the back, often splitting into a V-shape toward the rear, and commonly a prominent white stripe on their snout and forehead (Figure 1A). Tails are usually black with white hairs along the edges. Striped skunks are stout animals with small ears, short legs, and well-developed claws for digging. The striped skunk is about the size of an ordinary house cat, and ranges from 18–32 inches in total length. Striped skunks typically weigh about 8 pounds and may vary from about 2–14 pounds, and they may lose up to one-half of their body weight over winter.

The western spotted skunk tends to be smaller and more slender than the striped skunk. Their total length varies between 14–18 inches and weigh from less than 1 pound to about 1.5 pounds. Their fur is black with distinctive white marks on the forehead, and parallel white stripes running down the neck and about halfway down the back (Figure 1B). White stripes, parallel to the stripes on the back, begin under the ear and run along each side of the body to about the mid-point. Beginning at about the body’s mid-point and down to the tail region are two stripes that cross over the back and are roughly perpendicular to the stripes on the front half of the body. Behind the posterior stripes are spots located on the upper thigh and on each side of the tail. Stripes may vary greatly in broken or spotted form. The western spotted skunk is found throughout New Mexico.

The hog-nosed skunk has a prominent naked nose pad from which it derives its name (Figure 1C). They tend to have a white, wedge-shaped stripe that extends onto their back. The stripe on the back may be solid white and run the entire length of the body or it may split into two white stripes. The tail tends to be white on top and may be black or white underneath near the base. Total body length is about 17–37 inches and weight is typically 2–10 pounds. Hog-nosed skunks have stocky legs and long front claws well adapted for digging. In New Mexico, they are typically found in the southern portion of the state and east of the Rio Grande into southeastern Colorado. It is now thought to be largely absent from the Rio Grande Valley where it was once common.

The hooded skunk looks similar to the striped skunk with the addition of long hairs on the back of the neck and head that form a hood (Figure 1D). Their tails tend to be long and mixed with white and black hairs. They are generally smaller and slimmer compared to striped skunks but larger than spotted skunks. Total length is about 22–31 inches and weight may range from less than 1 pound to about 6 pounds. Their tails are longer than their body and their fur tends to be longer than other skunk species. Hooded skunks have three distinct color patterns: white-backed, black-backed, and solid black. The white-backed pattern skunks are white along the back from behind the ears (forming a hood) to the base or even end of the tail; they may also have a white stripe running along each side, below the back. The black-backed pattern has a solid or nearly solid black back with white stripes running along each side. Hooded skunks may have a thin white stripe running down their forehead and between their eyes. In New Mexico, hooded skunks are most often observed in the southwestern portion of the state. Regardless of the species, coloration in skunks is highly variable, ranging from solid black to nearly all white.

Figures 1A–D. A) Striped skunk (courtesy of Alfred Viola, Northeastern University, Bugwood.org), B) western spotted skunk (courtesy of Brian Kentosh), C) North American hog-nosed skunk (courtesy of Saguaro National Park, Flickr.com), and D) hooded skunk (courtesy of Pat Gaines, Flickr.com). Note: There may be considerable variation in coloration and stripe patterns among individuals and species.

Habitat

In the U.S. Southwest, skunks inhabit woodlands, grasslands, deserts, and agricultural, suburban, and urban environments. Rocky bluffs, brush-bordered agricultural fields, vegetated streambeds and riparian areas, arid lowlands, forests, mesquite grasslands, scrub-cactus rangelands, and livestock pastures are also home to skunks. They generally den in a burrow, rock crevice, hollow log, debris piles, under buildings, or in abandoned vehicles. Western spotted skunks will also climb trees and use hollow limbs as dens. Striped and spotted skunks are known to live in close association with humans, while hooded and hog-nosed skunks are less attracted to human environments. Skunks live at elevations ranging from sea level to greater than 10,000 feet, but are typically found at elevations less than 8,000 feet. The home ranges of skunks are typically 0.5–2.0 miles in diameter and vary depending on location and habitat quality. Spotted skunks tend to have smaller home range sizes than striped skunks.

Food Habits

As omnivores, skunks are opportunistic feeders and change diets quickly to exploit an available food source. During summer, skunks eat large quantities of insects, including grasshoppers, crickets, beetles, worms, and grubs. They also eat crayfish and scorpions as well as amphibians, reptiles, and carrion. During cooler months, skunks eat mice, voles, rats, and other small mammals as well as birds and eggs. While typically comprising a lesser portion of their diet, skunks eat plant foods in the form of foliage, roots, seeds, nuts, and fruits. When they live near humans, skunks also eat garbage and other refuse when available.

General Biology

Skunks are primarily nocturnal. They may also be crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk). Hog-nosed skunks have been observed feeding during daylight hours in winter and summer months in Texas. Skunks observed during daylight may be sick and should not be approached. Skunks tend to be solitary, except for females with the young of the year. Skunks become dormant during the coldest part of the winter and may reside in communal dens with several other individuals. Some species may occupy multiple dens throughout the winter dormancy season. Spotted skunk winter den sites have been reported to hold up to 20 females. Male skunks tend to remain active unless weather is especially adverse. Skunks may not become dormant in areas that do not have a cold winter period. Maximum lifespan of wild skunks ranges from 3–7 years, with the majority of skunks living less than one year. Male skunks are larger than females.

Skunks reproduce once per year, and litter size varies depending on species. Young skunks are altricial, being born naked and blind and requiring parental care for the first few weeks of life. Breeding season for striped skunks is February through April, western spotted skunks breed in September and October, and hooded and hog-nosed skunks breed from February through March (Table 1). During the breeding season, males often travel greater distances than normal as they search for possible mates. Female skunks tend to aggressively resist male skunks unless receptive to breeding. Skunks may delay implantation of the embryo from a few days to several months depending on species; this accounts for the early breeding season and long gestation estimated for western spotted skunks (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Estimated Breeding Season, Gestation, Parturition (Birth), Range of Number of Offspring, and Age at Sexual Maturity for Four Skunk Species Found in New Mexico |

||||

|

Striped skunk |

Western spotted skunk |

Hooded skunk |

Hog-nosed skunk |

|

|

Breeding season |

Feb.–Apr. |

Sep.–Oct. |

Feb.–Mar. |

Feb.–Mar. |

|

Gestation (days) |

59–77 |

210–230 |

60 |

60 |

|

Parturition |

Apr.–Jun. |

Apr.–May |

Apr.–May |

Apr.–May |

|

Number of offspring |

5–9 |

1–6 |

3–6 |

2–5 |

|

Age at sexual maturity (months) |

10 |

4–5 |

10 |

10–11 |

Predators of skunks include humans, great horned owls, golden eagles, bald eagles, mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, gray and red foxes, and American badgers. Birds of prey appear unaffected by skunk musk. Skunks are often described as docile or self-absorbed because they tend to ignore other animals. Despite their apparent indifference, skunks are known to defend themselves by accurately discharging a concentrated musk.

Skunk Defense

Skunks tend to be docile and may not acknowledge human presence until they feel threatened. It is possible to approach a skunk closely before they react. All skunks have the ability to discharge a powerful and nauseating yellow musk from a pair of enlarged anal glands and can discharge this musk multiple times. Skunk musk contains a sulfur-based organic molecule called a thiol. These organic molecules are responsible for the intense scent of skunk musk. Thiols are also found in onions, garlic, rotting flesh, natural gas (added), and petroleum. Skunk musk may cause severe burning and tear production upon entering the eyes, making it difficult to see for several minutes. Breathing, especially through the nose, may be difficult as well. These responses to skunk musk allow skunks to escape predators and may leave predators wary of approaching skunks in the future.

Skunks exhibit a variety of behaviors before actually spraying a potential predator. Although skunks may run away and hide if time allows, more often they may just turn and face the threat. Then they may stomp their forefeet, raise up on their hind feet, and drop-stomp their forefeet while hissing loudly. They may charge toward the threat and click their teeth. They usually raise their tails up or lay their raised tail along their back. They may turn their hindquarters toward the threat, creating a tight U-shape with their body, before spraying. Spotted skunks are known for performing handstands and bending their hindquarters over their head to point at the threat. Other behaviors include scratching at the ground and throwing debris, hissing, and baring their teeth. Skunks may spray a mist while running away or produce a highly accurate stream aimed at the threat. If you encounter a skunk showing signs of spraying, retreat slowly and quietly while avoiding sudden movements and loud noises.

Odor Removal

Skunk musk is persistent and may be nauseating to some. Cleaning hard surfaces with a mild bleach solution helps break down the potent thiols. Other household cleaners may also be useful in cleaning hard surfaces that have been sprayed. Musk sprayed on hard surfaces, such as walls or siding, may remain pungent for several days post-exposure, but will dissipate. If a skunk has sprayed under a structure, place fans in front of openings or vents to create a cross draft to help ventilate the area. If recreating outdoors, smoke sprayed clothing over cedar, juniper, or other aromatic-wood fires. For absorbent surfaces, such as clothing, human skin, and animal fur, the musk soaks in, contributing to its persistence. After cleaning, absorbent materials such as pet fur may smell better when dry, only to express the musk scent again when wetted.

Skunk musk is yellow in color and may be seen on hard or light-colored absorbent surfaces. Light-colored pets may exhibit yellow musk stains when sprayed. Commercial odor removers to remove most of the scent from absorbent surfaces are readily available at pet stores, feed stores, or online. Be sure to read the label carefully before applying it to your person, clothes, or a pet to reduce the chance of harm or unintended consequences.

A proven home remedy developed by Paul Krebaum, first described in 1993 in the American Chemical Society’s Chemical & Engineering News, removes skunk scent by oxidizing the pungent molecules in skunk musk. See “The Skunk Remedy Recipe” (Krebaum, 1993).

The Skunk Remedy Recipe

In a plastic bucket, mix well the following ingredients:

1 quart of 3% hydrogen peroxide

1/4 cup baking soda

1 to 2 teaspoons liquid soap

For large pets, one quart of tepid tap water may be added to enable complete coverage.

Carefully follow the detailed instructions at https://wildlife.unl.edu/pdfs/removing-skunk-odor.pdf.

Benefits of Skunks

Skunks should not be needlessly destroyed. If possible, leave skunks alone to go on their way. Skunks’ food habits are beneficial to humans because they feed on insects, including those that are agricultural and garden pests, such as white grubs, cutworms, and potato beetle grubs, among others. Outside the growing season, diets change and they rely more on rats, mice, and other rodents that may cause damage or be a nuisance. With effective exclusion and habitat modification, skunks will be visitors instead of unwelcome residents.

Damage Assessment

Skunks become nuisances when their burrowing and feeding habits conflict with people, or they spray pets or people. They may burrow under foundations or occupy existing spaces under structures. Garbage or refuse left outdoors may also be disturbed or scattered by skunks. Sometimes skunks will feed on garden crops in suburban and urban areas. They dig holes in lawn turf, golf courses, and gardens to search for insect grubs found beneath the surface. Digging appears as small patches of disturbed sod or cone-shaped holes about 3–4 inches in diameter. Skunks have also been known to kill poultry and eat eggs.

Skunks may feed on corn during the milk stage, generally eating only on the lower ears and shredding the husks. This differs from squirrels who may also damage corn, but feed on the upper ears. Raccoons knock down cornstalks, while skunks do not. Skunks occasionally feed on ground-nesting birds, usually resulting in limited impacts to bird populations.

Skunks may damage beehives by trying to feed on bees. Damage may include claw damage to the bottomboard entrance or on the lower part of the hive box above the entrance. Although skunk damage to bee equipment may be minimal, they can cause considerable damage by killing bees, resulting in lost production and even colony collapse because of eating adult and larval bees.

Because striped skunks normally do not climb, loss of poultry that are enclosed by fencing may be the work of rats, weasels, mink, coyotes, foxes, bobcats, or raccoons. Multiple poultry killed in a single attack are more likely the result of weasels or raccoons. Uncontrolled dogs may be the cause of large numbers of birds being indiscriminately killed and mutilated. Coyotes and bobcats typically carry their prey off. Fences without buried skirting may not keep skunks out because they are excellent diggers and can squeeze under the bottom edge. When skunks raid chicken coops, they typically focus on eggs rather than poultry. When they do kill poultry, it is typically one or two birds. Skunks usually feed on the head and neck of poultry. Eggs are mostly opened on one end with the edges crushed inward. By comparison, weasels and mink typically crush the entire egg while foxes carry eggs away.

In and around the home, skunks may den under steps, along a foundation, under porches, under trailers with solid skirting, or under debris piles. If you suspect a skunk may be denning on your property, check around the foundations of structures and around debris piles to locate possible den openings. Den openings are approximately 3–6 inches in diameter.

Tracks can be used to identify the animal causing damage. Both the hind and forefeet of skunks have five toes. However, the fifth toe may not be obvious in a light track. Claw marks will be easily visible, and the heels of the forefeet are normally not imprinted. The hind feet tracks are approximately 2.5 inches long (Figure 2) for larger species. Skunk droppings are usually not observed, look similar to cat droppings, and differ by content since they may include insect parts. Presence or absence of odor is not a reliable indicator of skunk presence or activity.

Figure 2. Skunk tracks (forefoot and hind foot).

Skunks are associated with a variety of parasites and diseases that can affect humans and domestic animals. Parasites include fleas, lice, mites, ticks, botfly larvae, intestinal roundworms, ringworms, subcutaneous nematodes, and helminths. Diseases include rabies, canine distemper, canine parvovirus, leptospirosis, and tularemia. It is often not possible to predict when and where diseases may be found in skunks or cross over into human or domestic animal populations. It may be difficult to determine if an animal is sick through casual observation. Therefore, you should take precautions any time you may be exposed to areas frequented by skunks, when in close proximity to skunks, or handling their carcasses.

Skunks are known carriers of rabies and present safety concerns to humans, pets, and livestock. Rabid skunks may not show symptoms for several days or even weeks. Take care to avoid overly aggressive skunks that approach without hesitation. Any skunk showing abnormal behavior, such as daytime activity, tameness, or listlessness, should be treated with caution and avoided if possible. A skunk that refuses to spray when harassed by a pet may have rabies or another disease.

Safety Precautions

When working in areas frequented by skunks, handling materials exposed to skunks, or handling skunk carcasses, wear latex, nitrile, or similar impermeable disposable gloves.

Bag materials or carcasses by handling with a plastic bag and turning the bag out on itself prior to sealing. Place this bag in a second bag, add your disposable gloves, and then seal and place in the trash. Another carcass disposal method is deep burial. Check local laws to determine what constitutes a deep burial. Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water when the task is complete.

If you are bitten, seek medical attention immediately. If possible, contact appropriate authorities to capture the skunk. If you shoot the skunk, do not damage the head because the animal must be submitted to the New Mexico Department of Health’s Scientific Laboratory Division in Albuquerque for testing. Specific mailing instructions should be obtained before submitting specimens. Post-exposure preventive care may be administered based on a medical doctor’s determination.

Damage Management

Sanitization is an effective approach to preventing or limiting skunk problems by modifying habitat to minimize its desirability to skunks and rodents. Integrating multiple prevention and management strategies may be necessary to address skunk damage adequately.

Habitat Modification

Habitat modification includes any activity that alters access to or availability of food, water, and shelter. Garbage, pet food, and other food sources may attract skunks. Remove pet food and water bowls from outside when not in use. Even empty pet food bowls may attract skunks in search of a meal. Store pet food in metal containers with tight-fitting lids. Garbage cans with tight-fitting lids prevent skunk access and subsequent scattered trash. Rodents living in barns, crawl spaces, sheds, garages, or debris piles represent a source of food that may attract skunks. Managing rodent populations in these areas may be necessary and useful to reduce attraction to skunks. Cleaning up or removing debris piles reduces or eliminates potential den sites and harborage for rodents, an important winter food source.

Debris, such as lumber, fence posts, stone piles, and old vehicles, provides shelter for skunks and encourages use of an area. Stacking materials such as fence posts off the ground in a neat arrangement also reduces denning sites and rodent harborage. Place materials at least 18 inches off the ground. Do not use pallets as a base for materials because this creates refuge for rodents and skunks. Keep vegetation short around stacked materials. Combining exclusion methods with habitat modifications will decrease the desirability of an area for skunks.

Damage to lawns is often the result of grubs and other insects living in the root zone. These insects may attract skunks, and using insecticides on lawns should address the problem. You should follow the label directions for the application of pesticides, and it may take two or more weeks following treatment to notice a positive result.

Exclusion

Exclude skunks from denning under structures by sealing all openings along the foundation, but be sure the skunks are not currently denning there. Cover openings with wire mesh, sheet metal, or concrete. Where access can be gained by digging, obstructions such as fencing should be buried to prevent entry. Exclude skunks from window wells or similar depressions with well-secured hardware cloth (also known as galvanized welded wire). Protect mobile homes by burying fencing along the trailer skirt or placing a thick layer of 1- to 3-inch-diameter gravel in a 2- to 3-foot-wide band along the skirt’s base.

Protect beehives by placing them 3 feet off the ground. If skunks still disturb hives, it may be necessary to place aluminum guards around the base to protect them. Information is available online for building or purchasing hive guards.

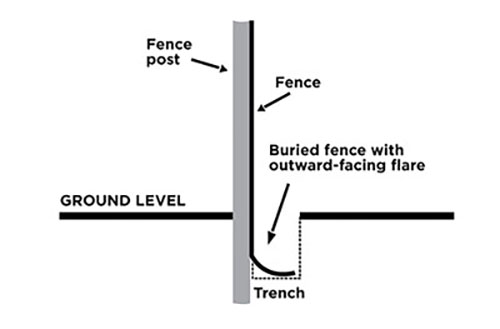

Protect outbuildings, such as sheds, workshops, and chicken coops, by sealing all ground-level openings into the building and closing doors at night. Poultry yards and coops without subsurface foundations can be fenced. Recommendations on how deep to bury fence skirting vary from 6–24 inches, with an outward-facing flare of 6–24 inches in length (Figure 3). Logically, the deeper the buried fence is in the vertical plane, the shorter the horizontal plane (outward-facing flare) needs to be. For example, burying fencing 6 inches deep vertically would benefit from a longer flare of about 24 inches. Conversely, burying 24 inches of fence vertically would require a shorter flare of about 6 inches. The fence flare should be oriented away (outward) from the protected area by bending the desired amount of fence to approximately horizontal at the bottom of the trench or adding an additional section of fence by securing it to the bottom of the vertical fence and orienting it near horizontal before backfilling.

Figure 3. Illustration of a buried fence to protect an area from skunks.

Repellents

There are no registered repellents for skunks.

Toxicants

There are no registered toxicants for use in controlling skunks.

Managing Individuals

Skunks may be caught in live traps set near the entrance of their den or near areas they are known to frequent. When more than one animal uses a den, setting several traps to reduce capture time may be advisable. Box traps can be purchased or built.

Effective baits for skunks include canned fish-flavored cat food, peanut butter, sardines, and chicken entrails. These baits may also attract non-target species, increasing the time and resources necessary to capture the intended animal. It has been suggested to use a broken, raw egg to reduce the potential for non-target captures. Skunks digging in your lawn may be difficult to trap because they may only be interested in the subsurface grubs and insects.

Skunk-specific live traps are typically made of materials forming opaque walls to limit vision and potential spray radius, and represent a secure environment for a skunk to explore. It is possible to convert a wire mesh live trap by covering it in roofing tarpaper secured with bailing wire. Other materials, such as open-ended plastic feedbags or canvas and poly tarps, can be used to similar effect. If necessary, move the trapped animal to an appropriate location before humanely killing the animal. With proper training, a gunshot results in instant and humane death. Contact local animal control agencies or businesses to inquire about the availability of a mobile euthanasia chamber. These devices slowly replace the air with carbon monoxide, resulting in humane death. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, drowning a trapped animal is decidedly inhumane. Release non-target animals at the location of their capture. Live-trapped skunks should not be translocated (relocated to an area outside their home range) because of the possibility of spreading rabies and other diseases.

Foothold traps can be used to capture skunks. However, caution is advised since exposure to spray may be increased when dispatching and removing the animal from the trap. Properly sized conibear traps (a type of kill trap) can be used. Conibear traps will kill cats and small dogs and should not be used in areas where they occur. Using safe and responsible methods of trapping is a personal obligation that must not be ignored. Check local laws prior to using foothold or conibear traps to capture a skunk.

Removing and Excluding Skunks From Under Structures

Avoid permanently trapping an animal under a structure because it will cause inhumane death by dehydration or starvation, and odor problems may subsequently occur. Follow these general guidelines for removing skunks under buildings prior to exclusion:

1. Leave the main burrow opening undisturbed and seal all other possible entrance points along the foundation. Entrances may be temporarily sealed using large rocks or other materials.

2. In front of the main opening, sprinkle a light dusting of flour on the ground about 2 feet across.

3. After dark, examine the sifted flour for tracks that indicate the skunk has left. If tracks are not present, re-examine in an hour. Alternatively, you can shine a flashlight into the burrow in an attempt to observe eye-shine.

4. Once the skunk has departed and the den is thought to be empty, cover the remaining entrance with hardware cloth. Bury the fencing and secure it to the sides of the structure.

5. Return to the entrance the next night and shine a light into the entrance to look for eye-shine of any skunks that may be trapped. Alternatively, reopen the entrance the next day about 2 hours after dark and leave it open to allow time for remaining animals to leave. Re-seal the entrance well before dawn.

6. Revisit the entrance for 2–3 days to ensure nothing has been entombed. Each time animals are observed behind the exclusion fencing, check along the base of the structure to ensure blocked side openings have not been reopened. When you are reasonably certain no animals remain under the structure, seal the entrance permanently.

Another approach to excluding resident skunks from under a structure is to place a one-way door at the burrow entrance. One-way doors are available for purchase locally or online. You can build a wooden door suspended from wire to allow skunks to leave a burrow but not re-enter.

In cases where skunks have entered a garage, cellar, or house, leave the doors open and allow the skunks to exit on their own accord. Do not prod or disturb them. Skunks trapped in a cellar window well or similar pits may be removed by placing a board at an angle into the pit. Lower the board slowly so as not to alarm the animal. Add cleats of wood or wire mesh to the board to increase traction.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge J.E. Knight (1994) and J.C. Boren and B.D. Wright (2003) for previous publications on New Mexico skunks.

References

American Veterinary Medical Association. 2013. AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals, 2013 ed. Schaumburg, IL: Author.

Anderson, N.K. 2020. Conepatus leuconotus, North American hog-nosed skunks. Animal Diversity Web. Accessed February 19, 2021, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Conepatus_leuconotus/

Bairos-Novak, K. 2014. Mephitis macroura, hooded skunk. Animal Diversity Web. Accessed December 21, 2018, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Mephitis_macroura/

Barnes, T.G. 1999. Managing skunk problems in Kentucky [Publication FOR-49]. Lexington: University of Kentucky, Cooperative Extension Service.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. n.d. Other wild animals: Terrestrial carnivores: Raccoons, skunks and foxes. Accessed April 30, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/exposure/animals/other.html

Clark, K.D. 1994. Managing raccoons, skunks, and opossums in urban settings. In Proceedings of the 16th Vertebrate Pest Conference, University of California, Davis (pp. 317–319).

Cuarón, A.D., K. Helgen, and F. Reid. 2016. Spilogale gracilis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T136797A45221721. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T136797A45221721.en

Cuarón, A.D., J.F. González-Maya, K. Helgen, F. Reid, J. Schipper, and J.W. Dragoo. 2016. Mephitis macroura. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41634A45211135. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41634A45211135.en

Dragoo, J.W., and R.L. Honeycutt. 1999. Eastern spotted skunk / Spilogale putorius. In D.E. Wilson and S. Ruff (Eds.), The Smithsonian book of North American mammals (pp.185–186). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Dragoo, J.W., and S.R. Sheffield. 2009. Conepatus leuconotus (Carnivora: Mephitidae). Mammalian Species, 827, 1–8.

Hakkinen, K. 2001. Spilogale gracilis, western spotted skunk. Animal Diversity Web. Accessed December 21, 2018, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Spilogale_gracilis/

Hayssen, V., A. van Tienhoven, and A. van Tienhoven. 1993. Asdell’s patterns of mammalian reproduction: A compendium of species-specific data. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Headings, M. 1999. Skunks aren’t good news. Bee Culture, 127, 36–37.

Helgen, K. 2016. Conepatus leuconotus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41632A45210809. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41632A45210809.en

Helgen, K., and F. Reid. 2016. Mephitis mephitis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41635A45211301. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41635A45211301.en

Kiiskila, J. 2014. Mephitis mephitis, striped skunk. Animal Diversity Web. Accessed December 21, 2018, from https://

animaldiversity.org/accounts/Mephitis_mephitis/

Knight, J.E. 1994. Skunks. In S.E. Hygnstrom, R.M. Timm, and G.E. Larsen (Eds.), Prevention and control of wildlife damage (pp. C-113–118). Lincoln: University of Nebraska.

Krebaum, P. 1993. Lab method deodorizes a skunk-afflicted pet. Chemical and Engineering News, 71, 90.

Mead, R.A. 1968. Reproduction in Western forms of the spotted skunk (Genus Spilogale). Journal of Mammalogy, 49, 373–390.

Means, C. 2013, March 31. Skunk spray toxicosis: An odiferous tale. Accessed February 18, 2019, from https://www.dvm360.com/view/skunk-spray-toxicosis-odiferous-tale

Mengak, M.T. 2018. Wildlife translocation [Wildlife Damage Management Technical Series 18]. Fort Collins, CO: USDA, APHIS, WS National Research Center.

Nowak, R.M. 1991. Walker’s mammals of the world, 5th ed., vol. 2. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rosatte, R., and S. Larivière. 2005. Skunks. In G.A. Feldhammer, B.C. Thompson, and B. Carlyle (Eds.), Wild mammals of North America: Biology, management, and conservation (pp. 692–707). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sullivan, K.L., and P.D. Curtis. 2001. Striped skunks [Wildlife damage management fact sheet series]. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Cooperative Extension.

Vantassel, S.M. 2012. The wildlife damage inspection handbook: A guide to identifying vertebrate damage to structures, landscapes, and livestock, 3rd ed. Lincoln, NE: Wildlife Control Consultant.

Vantassel, S.M. 2015, February. Test your skunk knowledge. Pest Management Professional, 84.

Vantassel, S.M., S. Hyngstrom, and D. Ferraro. 2005. Removing skunk odor [Publication NF05-646]. Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Cooperative Extension.

Wund, M. 2015. Mephitidae, skunks and stink badgers. Animal Diversity Web. Accessed December 21, 2018, from https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Mephitidae/

Yarrow, G.K., and D.T. Yarrow. 2005. Managing wildlife: On private lands in Alabama and the Southeast. Birmingham, AL: Sweetwater Press.

For Further Reading

L-202: Bats in Buildings: Proper Exclusion Techniques in New Mexico

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_l/L202/

L-209: Rodent Control and Protection from Hantavirus

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_l/L209/

H-172: Backyard Beneficial Insects in New Mexico

https://pubs.nmsu.edu_h/H172/

Sam T. Smallidge is the Extension Wildlife Specialist at New Mexico State University. He has degrees in wildlife and range management. His Extension program focuses on wildlife damage management, wildlife enterprises, and wildlife ecology and management education for youth and adults.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu.

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced, with an appropriate citation, for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

March 2021 Las Cruces, NM