Proper Exclusion Techniques in New Mexico

Guide L-202

Revised by Sam T. Smallidge

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University.

Author: Extension Wildlife Specialist. (Print Friendly PDF)

Photo by B. Bayanaa, 20101

Bats are unique and interesting animals. They also are among the most misunderstood mammals in New Mexico because of fears and misconceptions about them.

Bats belong to the mammalian order Chiroptera, which means “hand-wing.” While flying, most bats navigate by echolocation, a process for locating distant objects by sending out sound waves that bounce off objects and return to the bat. An impressive diversity of bats is found around the world; Chiroptera is the second largest order of mammals, with more than 1,000 species (only the order Rodentia contains more).

A few species of bats are solitary, but most congregate in groups or colonies. They leave their roosting places at dusk to fly about in pursuit of insects, which make up the bulk of their diet. Some bats migrate with the change in seasons, following the food supply. Others remain in New Mexico, hibernating only during the colder months.

Almost all bats found in New Mexico are beneficial and of some economic importance. Most bats are insectivorous and may consume more than one half their body weight in insects each night. A large colony can eat literally tons of insects annually. Some bat species pollinate trees and cacti, providing a service similar to that of bees; bats pollinate some species of agave in New Mexico.

Despite their immense value, problems sometimes arise when bats enter buildings, and it may be necessary to use control measures.

Damage

Originally, bats roosted in natural shelters such as caves and hollow trees. Many still do, but others have found human dwellings much to their liking. Attics, spaces between walls, and unused areas in upper stories of buildings all make good roosting sites for bats. Although bats rarely do actual damage to dwellings, their presence is usually objectionable. Bat droppings and urine create a highly undesirable odor. If not cleaned thoroughly, this odor can persist for a long time and could attract additional bats. A naturally occurring soil fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum, is sometimes present in bat and bird droppings. Inhalation of the fungal spores can lead to histoplasmosis, a respiratory disease with symptoms similar to influenza. A HEPA respirator should be worn while cleaning large quantities of bat or bird droppings in a confined area to avoid inhalation of fungal spores that may become airborne when droppings are disturbed. Another approach is to hire a professional cleaning company with the equipment and knowledge to safely clean up bat guano5.

Noise is another problem often encountered with bats inside dwellings. A group of bats can create substantial noise by crawling and squeaking. This noise can be quite disturbing to humans5.

Bats, like other mammals, can transmit the rabies virus to humans if they are infected3. However, only a small percentage of bats are infected, and bat rabies accounts for an average of less than one human death per year in the United States2. Clearly, bats do not rank very high among mortality threats to humans. Nevertheless, prudence and simple precautions can save lives. Any bat acting in an abnormal manner should be approached with caution and not handled, particularly if found fluttering on the ground.

Control Methods

Before attempting to control bats, it is essential to verify that bats are the cause of the nuisance. For example, scratching or thumping sounds in the attic or walls may indicate the presence of birds, rats, mice, squirrels, raccoons or other animals.

The only way to permanently rid a building of bats is to eliminate all possible entrances. It must be emphasized that other control methods are not permanent solutions. Excluding bats from a building is the only efficient and permanent way to eliminate bat problems6.

Excluding Bats from Buildings

Bats may enter buildings through openings such as louvers, vents, broken windows, worn-out siding or holes around eaves and cornices. Other problem areas are faulty ridge vents, crevices in the soffit and fascia, chimneys that have slumped away from buildings, loose flashing, and the interiors of abandoned chimneys4. Smaller bat species can crawl through slits as narrow as 3/8 of an inch. Therefore, it is essential to seal all openings 1/4 inch or larger.

Bats should not be excluded from roosts when females are raising pups, generally May through August in New Mexico. Mothers often leave young bats in the roost when foraging at night. If bats are excluded during this time, the pups will be inadvertently trapped inside the roost and may die. Some bats hibernate in buildings during the winter months. Winter exclusions should be performed only if it can be determined that no bats are hibernating in the building. If bats are present during the winter months, exclusions should be postponed until the spring2.

The first step in any bat exclusion process is to examine the building to determine where bats are entering and exiting the roost. Look for brown stains at the roost openings during the daytime. These are caused by oils on the bats’ fur rubbing off on the outside surface of the building. Also look for black guano (droppings) beneath roost openings. Generally, most occupants will leave the roost at dusk and within 30 minutes after the first bat exits, although bats may leave the roost at any time during the night. Observing the building within an hour after dusk is the best way to locate openings used by bats as they fly out. If bats have been recently disturbed, keep in mind that their routine may be temporarily disrupted.

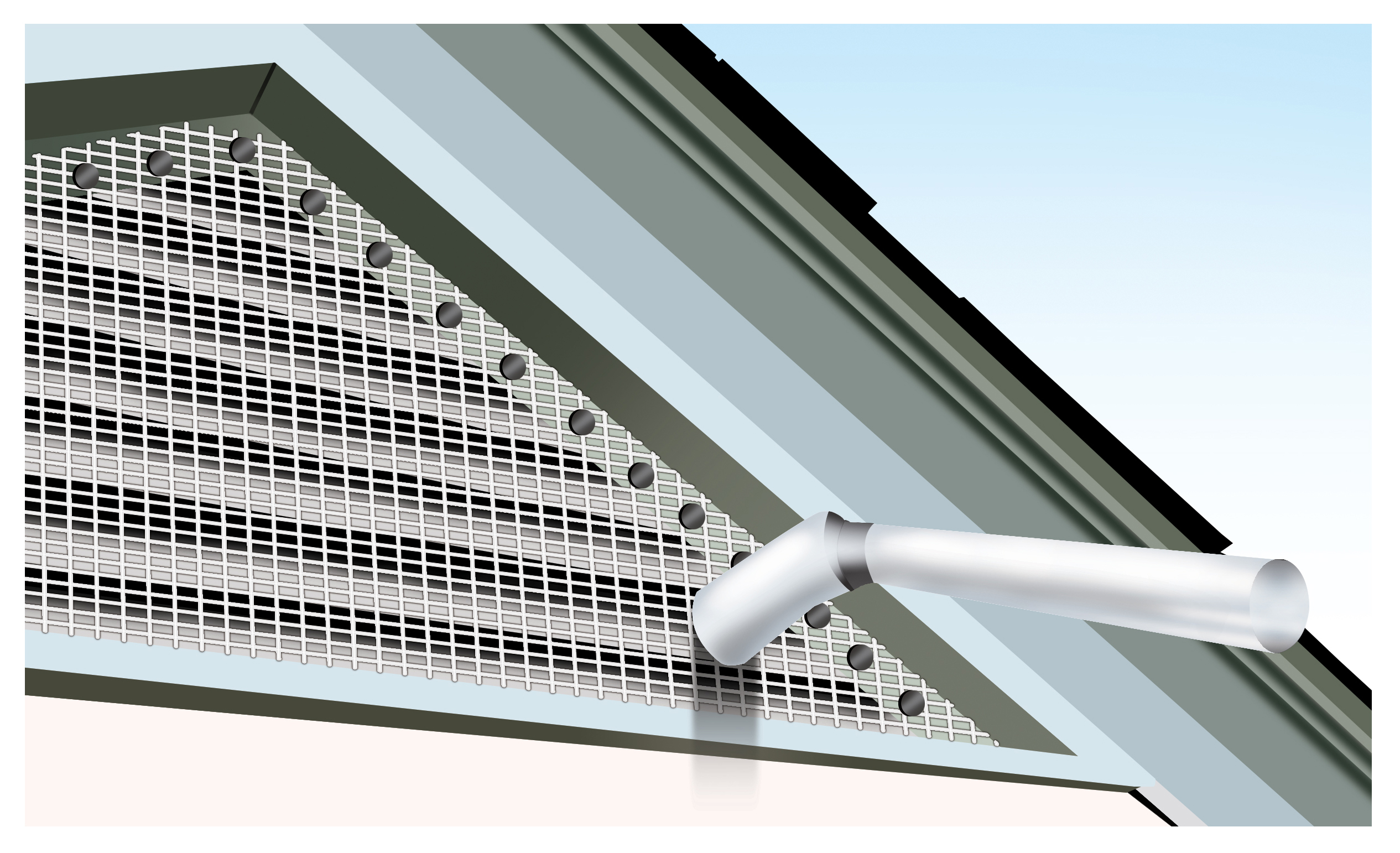

Figure 1. Bat exclusion screen with modified bat cone attached.

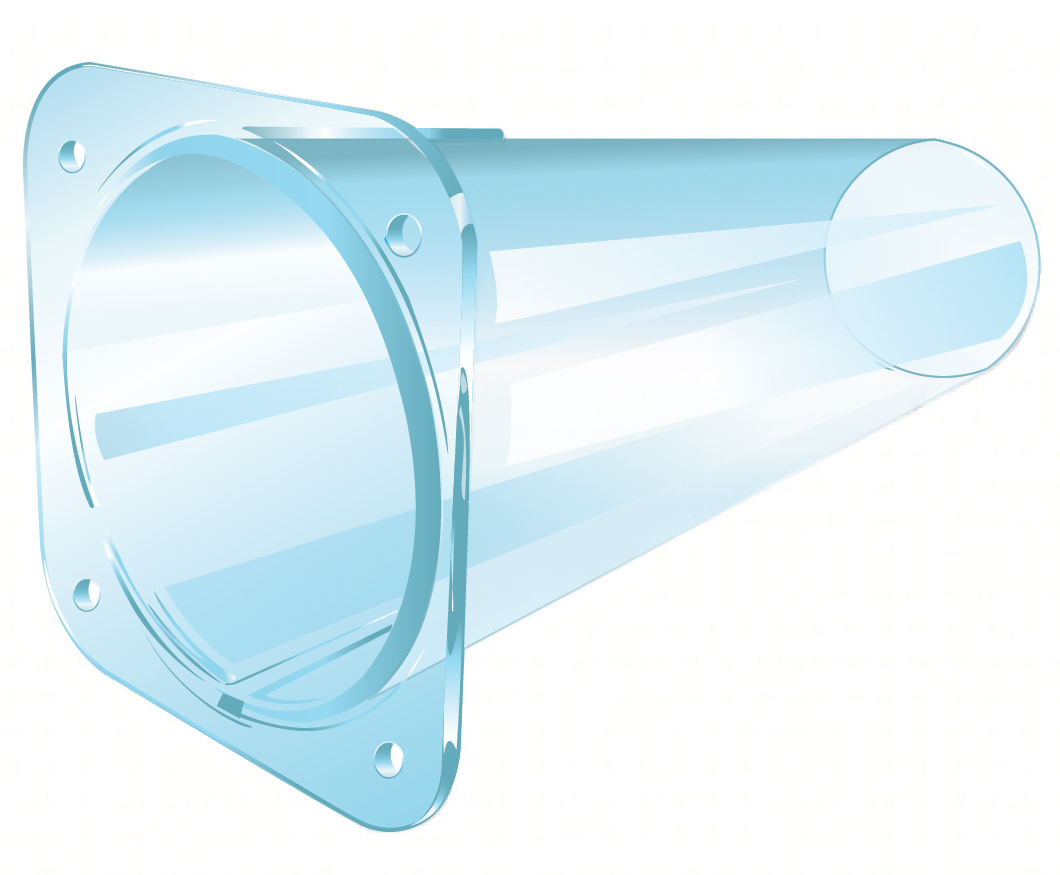

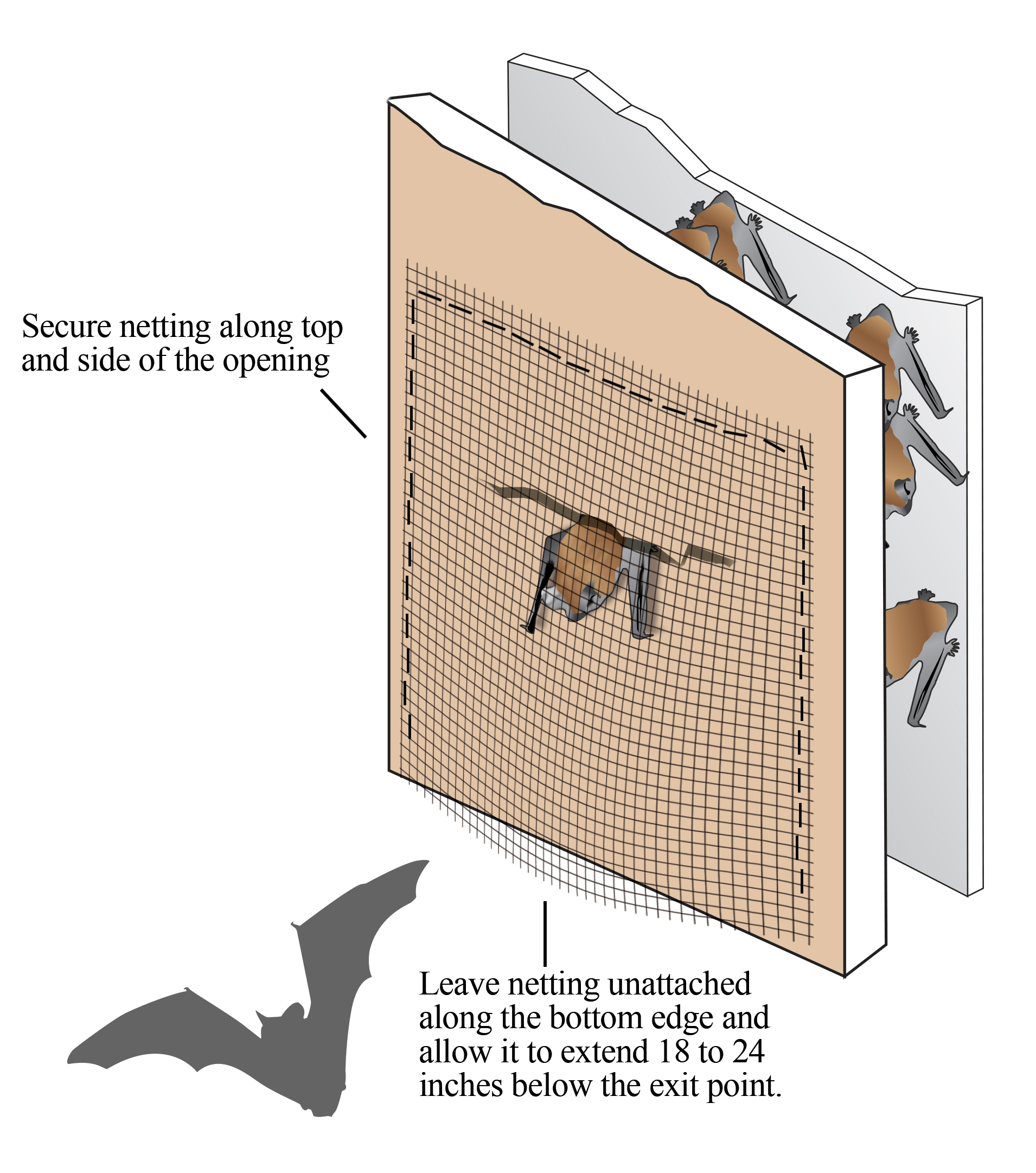

The next step after identifying the primary openings is to seal all other openings that may allow a bat to enter the building. Once this is accomplished, place a bat cone (also called a bat valve) as a one-way exit that allows bats to exit but not re-enter the building (Figure 1). There are a variety of these devices on the market and can be purchased online or at a local hardware store. Installing these cones may require additional materials (wood, plastic sheeting, etc.) to fit the cone tightly over the exit hole. Another and equally effective approach is to screen all potential openings with lightweight polypropylene netting (e.g., window screen) fastened in a way that allows bats to escape but not re-enter. You may purchase window screen material at any home improvement store—do not use wire screening as it is not flexible. The top of the flexible netting is affixed to the building at the roost exit and draped down a couple of feet below the opening (Figures 2). This serves as a one-way door: bats will exit the roost and crawl down and out from under the screen, but when they return and attempt to land, their re-entry is blocked by the screen. Leave the netting up for 5–7 days and observe the bats exiting at night to see that progressively fewer bats are leaving each night and to ensure that they are not simply using alternative openings.

Figure 2. Using netting to exclude bats.

Once all bats are gone, the remaining holes can be sealed, permanently excluding bats. Construction adhesive or caulking can be injected in cracks, crevices or any smaller entrances. Construction adhesive dries brown and may be painted over. Larger crevices may need to be stuffed with fiberglass screening as fill before being caulked over4. Large openings should be covered with sheet metal or with 1/4-inch mesh hardware cloth if ventilation is necessary. Foam is very messy to work with and can kill animals that come into contact with it; it should only be used in very complex or hard-to-reach areas. Bats, unlike rodents, will not chew their way back into a roost.

Bats may take up residence in nearby buildings unless possible entrances are sealed prior to excluding them from their current roost. Consider building and erecting a bat house to provide them a new home prior to their eviction. Bat houses may be purchased or you may build one; plans for building and erecting bat houses are available online.

Repellents

Occasionally, temporary control can be accomplished by using chemical repellents. Aerosol dog and cat repellents may discourage bat use of a particular roosting spot or prevent bats from night roosting above porches2. The spray should be applied by day when bats are not present. However, aerosol repellents are not an adequate substitute for exclusion in the case of day roosts.

Exclusion using one-way netting is a much more effective and permanent solution, although repellent techniques can sometime be used while bat-proofing is underway.

Trapping

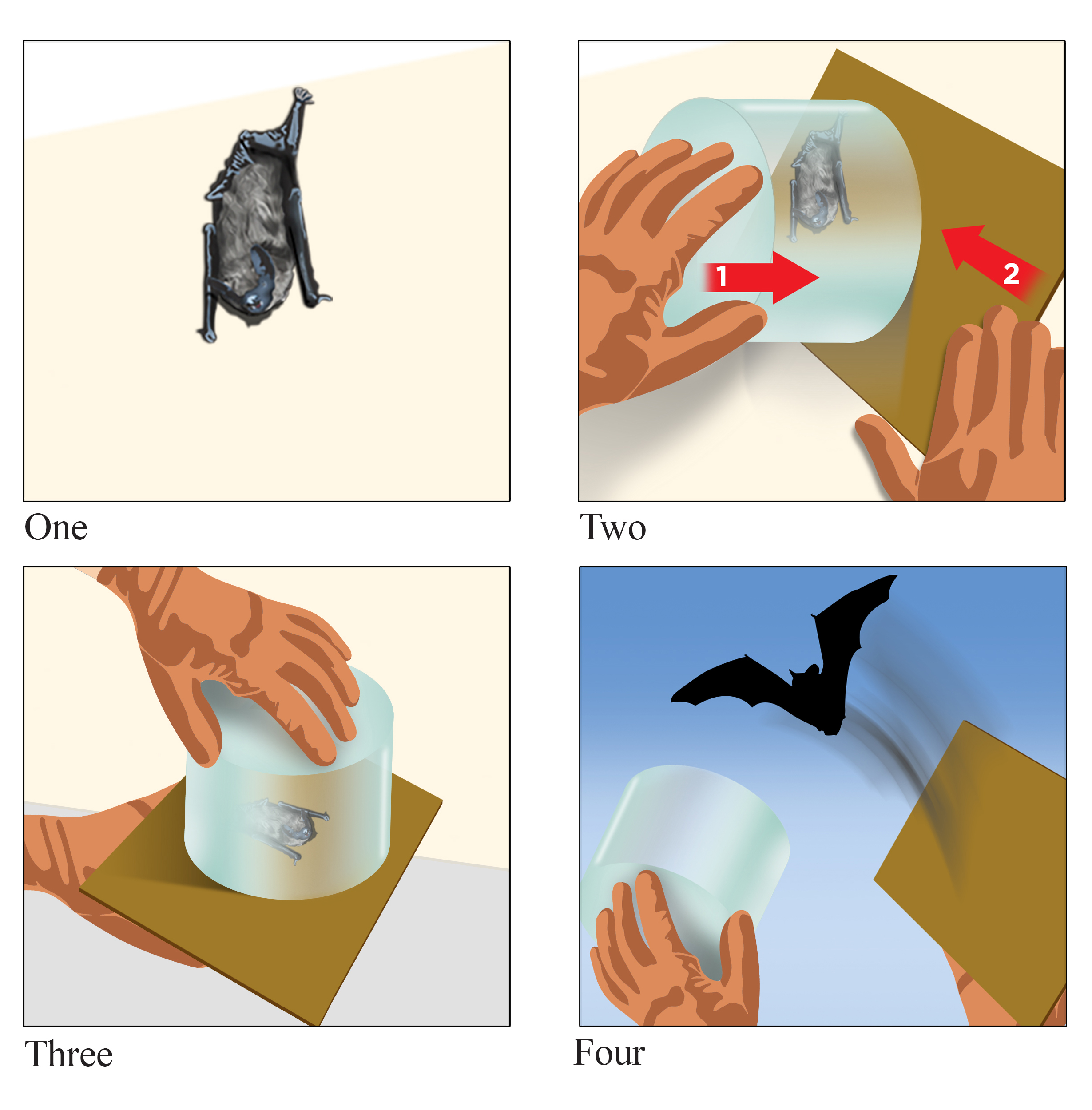

Figure 3. Live capture of a single bat for release outside.

Occasionally, a single bat may get into the living area of a house or building. Although this can be both disturbing and alarming, the bat will often leave at dusk if doors or windows are left open and lights are turned off. If they refuse to leave, they can be captured with a net or a small box. Simply approach the bat quietly, place the container over the bat and slide a rigid sheet of paper between the wall and the lip of the container (Figure 3). This paper acts as a lid and will allow you to take the bat outside and release it. Never touch a bat with your bare hands, and always wear leather gloves when attempting to capture them with a box or net. Although not usually aggressive, like other wild animals, bats may attempt to bite when handled.

Lethal Control

Lethal control is not necessary or recommended. As discussed earlier, bats are beneficial and, except under rare circumstances, destroying them is unwarranted. Many bat species occur in New Mexico, and many species are protected by state and/or federal law. Therefore, before conducting any type of lethal bat control, contact your local representative of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for information on species status. Consultation with this agency is recommended to ensure proper steps are used in addressing your bat issues. For more information and ideas on bats you may also contact USDA’s Wildlife Services at (505) 346-2640 and Samuel T. Smallidge, Professor and Wildlife Specialist, Department of Extension Animal Sciences and Natural Resources, (575) 646-5944.

Conclusion

The use of bat cones or one-way netting to exclude bats is the most simple, efficient, and effective way to batproof a building. The use of repellents is only temporary and lethal control rarely warranted. As long as the structure remains accessible to bats, you may continue to have problems. This can only be resolved with permanent exclusion.

Acknowledgements

Much of the information for this publication was adapted from:

- Bayan, B. (2010). Bats... [Photography]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/bayanaa-kofuku/5011423855/ [CC BY 2.0]

- Bat Conservation International. (2006). Bats and Building Program. www.batcon.org.

- Center for Disease Control. (2006). Bats and Rabies. www.cdc.gov.

- Chenger, J. (2006). Bat Conservation and Management. www.batmanagement.com.

- Henderson, F.R., & Lee, C. (1992). Bats: Urban Wildlife Damage Control [L-855]. Kansas State University, Cooperative Extension Service.

- Texas Wildlife Damage Management Service. (1998). Wildlife Damage Management: Controlling Bats [L-1913]. Texas Wildlife Damage Management Service.

The author also would like to thank Trish Griffin, New Mexico Bat Working Group Coordinator; John Chenger, Bat Conservation and Management Inc.; and Barbara French, Bat Conservation International, for their review and suggestions.

Original Publication: Jon Boren, Associate Dean and Director, Cooperative Extension Service; and Byron Wright, former Extension Wildlife Specialist. July 2001.

Consecutively revised by Jon Boren, August 2007.

Sam T. Smallidge is the Extension Wildlife Specialist at New Mexico State University. He has degrees in wildlife and range management. His Extension program focuses on wildlife damage management, wildlife enterprises, and wildlife ecology and management education for youth and adults.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu.

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

Revised December 2024, Las Cruces, NM.