Guide B-718

Jason L. Turner

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Author: Extension Horse Specialist, Department of Extension Animal Sciences and Natural Resources, New Mexico State University. (Print Friendly PDF)

Introduction

The first epidemic of eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) was reported in the 1830s in Massachusetts, and it affected both horses and humans. Since then the virus has been detected in all states east of the Mississippi River as well as some west of the Mississippi, including Arkansas, Minnesota, South Dakota, and Texas. It is commonly found along the Gulf Coast from Texas to Florida, in the Atlantic coastal states, and in some Midwestern states around the Great Lakes.

As the name implies, it causes encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain and neural tissues, in equines (horses, mules, burros, donkeys, and zebras). It can also infect (but is less common in) cattle, sheep, dogs, cats, pigs, llamas, alpacas, deer, bats, reptiles, amphibians, and rodents. Passerine birds serve as the primary reservoir for the virus. There is great concern for EEE as a zoonotic disease of humans that causes flu-like symptoms, encephalitis, and even paralysis, permanent brain damage, and death.

© Rebecca Hermanson, Dreamstime.com

Clinical Signs

The incubation period in horses, or the time from infection with EEE virus to the onset of clinical symptoms, is five to 14 days. While some animals may have mild cases without neurological symptoms, the initial signs include fever, loss of appetite, and depression. As the disease progresses, the neurological symptoms develop, which include altered mental activity, hypersensitivity to stimuli, involuntary muscle movements, paralysis, convulsion, inability to swallow, and incoordination. In addition to partial or total blindness, the horse may develop swollen eyelids and flaccid lips, and the tongue may hang from the mouth. Other observed signs include head pressing, leaning against objects, circling, staggering, and grinding of teeth. In most cases, the horse dies within three to five days after developing clinical symptoms. The fatality rate for EEE can be as high as 90% in horses that develop encephalitis. Of those that may recover, many surviving equines have severe and long-term neurological damage.

Disease Transmission

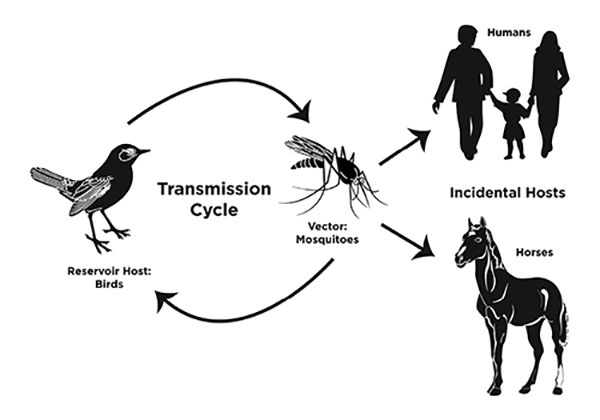

The EEE virus is usually maintained in wild populations of passerine birds. These birds do not develop the clinical disease, but they serve to grow the virus, which is spread between birds when mosquitoes (primarily Culiseta melanura) feed on them. Since this specific mosquito does not feed on mammals, it is not responsible for transmission from birds to mammals. However, several other species of mosquitoes feed on both birds and mammals and serve as the vector that transmits the virus from birds to horses, humans, and other mammals (Figure 1). Both equines and humans are considered “dead-end” hosts because they may develop the disease, but they do not have a high enough degree of virus replication sufficient to transmit the virus to other mammals or mosquitoes.

Figure 1. Transmission cycle for eastern equine encephalitis virus (adapted from Cornell University, 2018).

While EEE outbreaks are most prevalent during the summer and fall in temperate regions, the disease can be seen year-round in tropical environments. The outbreak normally ends when freezing temperatures eliminate infected mosquito populations. Although the process is not well understood, the virus may overwinter in reptiles, by transmission between different species of mosquitoes, or perhaps by reintroduction from migratory birds that harbor the virus.

Prevention

Since there is no treatment for the EEE virus (other than supportive care), it is best to prevent disease occurrence by using licensed vaccines that are commercially available in the U.S. Since these vaccines became available, the incidence of EEE has greatly decreased. The few EEE outbreaks that are seen typically occur in unvaccinated horses or in areas of the country where the long mosquito season may outlast the duration of protective immunity provided by annual vaccination. Therefore, it is common to administer the annual booster vaccination just prior to the start of “mosquito season” in the area. It is important that equine owners work with their veterinarian to develop a vaccination program for EEE that fits their individual needs and risk of exposure. The core vaccination guidelines of the American Association of Equine Practitioners (www.aaep.org) can provide some basic recommendations to initiate this discussion.

Other preventive measures can minimize the risk of exposure to mosquitoes that transmit the EEE virus to horses and other animals. These include:

- Reduce standing water, which provides an area where mosquitoes can reproduce. This includes draining water from any item that can hold water (e.g., old tires, flower pots, children’s toys, etc.). Tanks or other water sources for animals should be cleaned at least once per week to prevent mosquito growth. When the water source can’t be “cleaned,” using an approved larvicide, such as Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (Bti), can reduce mosquito numbers.

- Reduce areas that may provide cover for adult mosquitoes by mowing weeds and tall plants.

- Using screens, fans, or insecticide fogging systems for stabled horses can reduce their exposure. To further minimize the risk of exposure, coordinate riding or turn-out times outside of peak mosquito activity, which is normally around dusk and dawn, and avoid turning on lights in the stables during the evening or overnight period.

- In non-stabled horses, fly masks, fly sheets, and insecticides or mosquito repellents are effective. Be sure to follow manufacturer label directions for the specific product used.

- Owners should also protect themselves against mosquitoes by wearing clothing that covers their skin, such as long sleeve shirts or gloves, while wearing a DEET-containing repellent, and avoiding the outdoors during peak mosquito activity times.

Conclusion

Equine owners should understand the severe consequences of EEE virus in their animals as well as the risk for disease in humans. Therefore, it is important that responsible owners use the effective EEE vaccines available and other mosquito control practices to minimize the risk of their horse developing the fatal disease.

References

American Association of Equine Practitioners. n.d. Core vaccination guidelines [Online]. https://aaep.org/guidelines/vaccination-guidelines/core-vaccination-guidelines

Cornell University. 2018. Eastern equine encephalitis [Online]. https://cwhl.vet.cornell.edu/disease/eastern-equine-encephalitis

Gibbs, E.P.J., and M.T. Long. 2007. Equine alphaviruses. In D.C. Sellon and M.T. Long (Eds.), Equine Infectious Diseases, 1st ed. (pp. 191–197). St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier.

Hansen, I.A., et al. 2017. Stop those suckers [Infographic; online].

Merck & Co., Inc. 2020. The Merck veterinary manual [Online]. https://www.merckvetmanual.com

Spickler, A.R. 2017. Eastern, western and Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis [Online]. https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/easter_wester_venezuelan_equine_encephalomyelitis.pdf

United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2017. Bti for mosquito control [Online]. https://www.epa.gov/mosquitocontrol/bti-mosquito-control

For Further Reading

B-708: Documents Required to Transport Horses in New Mexico

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_b/B708/

Guía B-708: Documentos Requeridos para el Transporte de Caballos en Nuevo México

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_b/B708sp/

B-716: Equine Herpesvirus in Horses

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_b/B716/

B-717: Vesicular Stomatitis Virus in Horses

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_b/B717/

B-719: West Nile Virus in Horses

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_b/B719/

Jason L. Turner is Associate Professor and Extension Horse Specialist. Jason was active in 4-H and FFA while growing up in Northeastern Oklahoma. His M.S. and Ph.D. studies concentrated on equine reproduction, health, and management. His Extension programs focus on proper care and management of the horse for youth and adults.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu.

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced, with an appropriate citation, for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

July 2020 Las Cruces, NM