Bulletin-794

Cristina Carmona Martínez, Javier Martínez Nevarez, Abelardo Diaz Samaniego, and Rhonda Skaggs

Agricultural Experiment Station

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Authors: Former Graduate Research Assistant, Department of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business, New Mexico State University; Director of the Facultad de Zootecnia and Research Assistant, respectively, both of Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, Chihuhua, México; and Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces.

(Print friendly PDF)

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Methodology

The Sample

Results of the Survey

General Information about the Producer/Exporters

Respondents’ Cattle Exporting and Marketing Practices

Ports-of-Entry Used to Export Cattle

Reasons for Involvement in Livestock Industry

Attitudes toward the North American Free Trade Agreement

Problems Experienced in the Cattle Export Process

Perceptions of the Future of Domestic and Export Cattle Markets

Government Program Participation

Respondents’ Evaluation of Their Cattle

Modern Cattle Management Practices

Imports of Cattle from Central and Southern Mexico

Breeding Animal Acquisitions and Genetic Quality

Animal Identification Systems

Sources of Information

Economic Diversification

Technology Available on Respondents’ Ranches

Grazing Resources

Cattle Inventory and Production Information

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT)

Conclusion

References

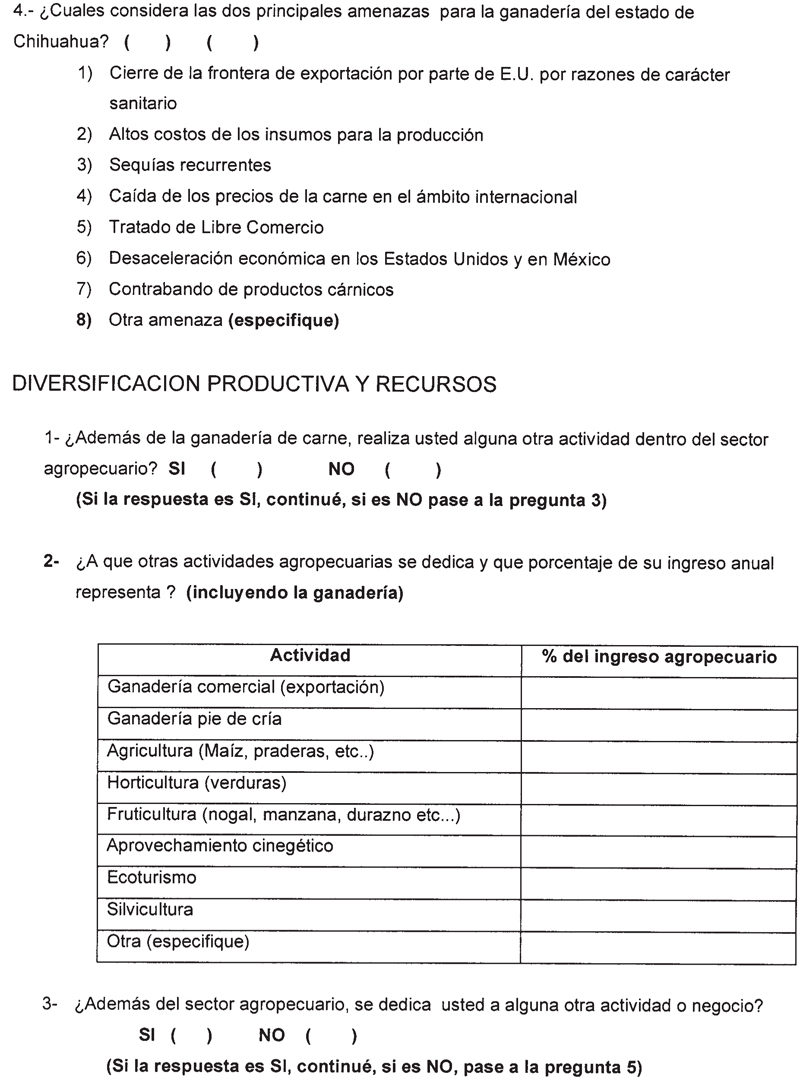

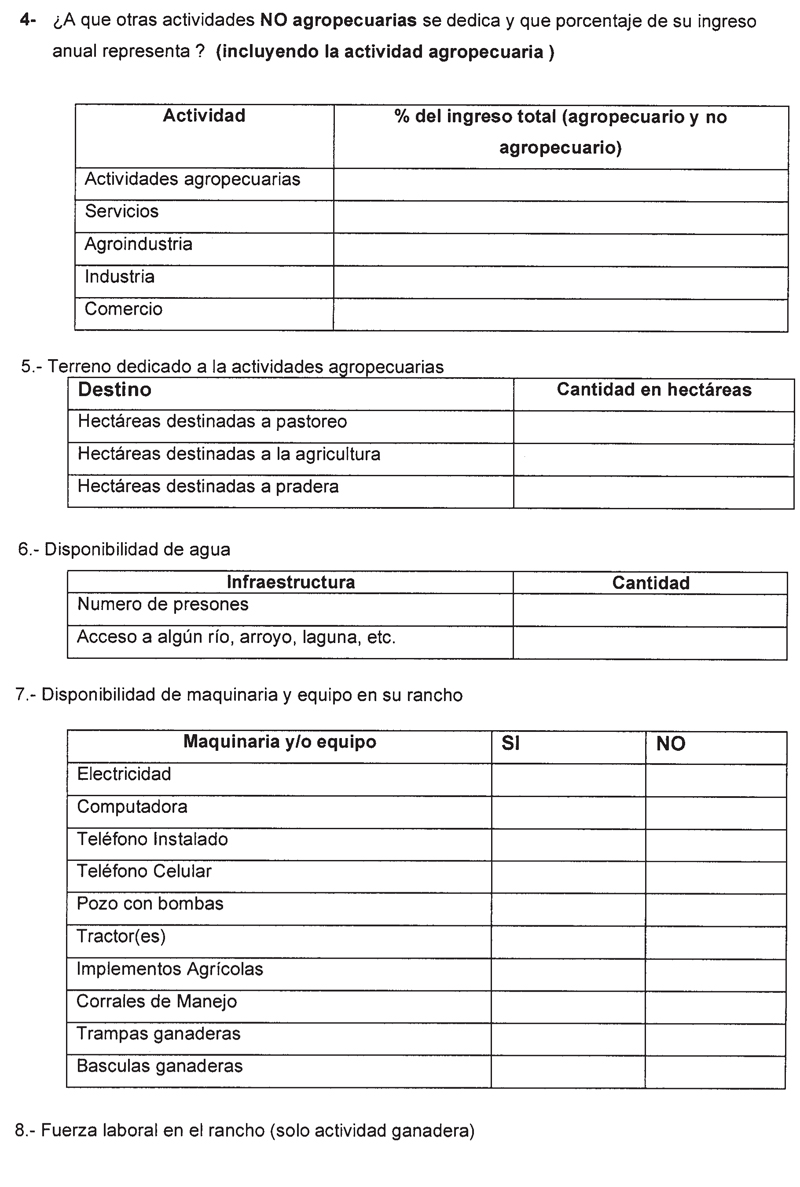

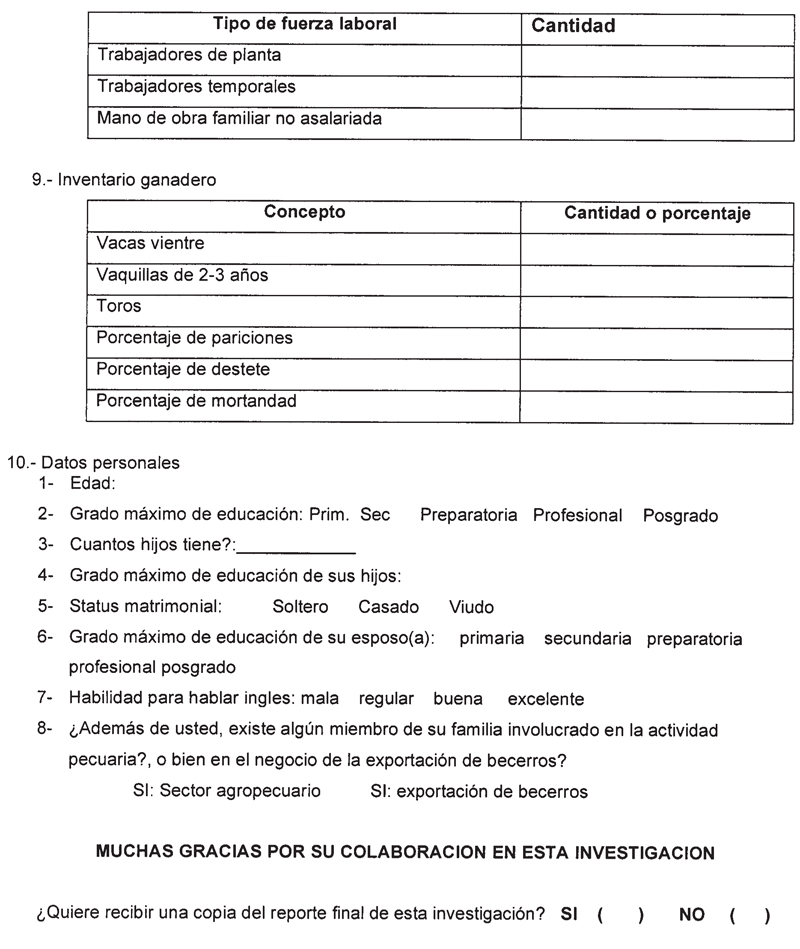

Appendix I: Survey Instrument

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Cristina Carmona, Ing. Zootecnista, in partial fulfillment of requirements for the Master of Agriculture–Specialization in Agribusiness degree. The report was prepared under the direction of Dr. Rhonda Skaggs, Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, New Mexico.

The research reported here was conducted with the cooperation and assistance of M.C. Javier Martínez Nevarez, Director of the Facultad de Zootecnia and Abelardo Díaz Samaniego, Research Assistant, both with the Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, Chihuahua, México.

This research and the preparation of this publication received financial support from a United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service cooperative agreement, the Center for North American Studies at NMSU, and from the New Mexico Agricultural Experiment Station.

This research is reported in both English and Spanish. Cristina Carmona translated the manuscript from English to Spanish.

Introduction

Chihuahua state is the most important cattle exporting region in Mexico (Martínez Nevarez 2002). Chihuahua is the largest Mexican state, covering 24,708,700 hectares (62,700,000 acres). The primary user of Chihuahua’s land resources is the state’s livestock industry. Chihuahua’s livestock identity is that of land extensive beef cattle production. Compared to all other Mexican states, Chihuahua is the 9th largest in terms of total cattle inventory (Martínez Nevarez 2002). In terms of total weight of cattle produced, Chihuahua ranks 5th among Mexican states (Martínez Nevarez 2002). Furthermore, Chihuahua is the leading state with respect to total numbers of cattle exported to the United States (Martínez Nevarez 2002).

The cattle industry in Chihuahua depends on grazing, and forage resources are limited by seasonal rainfall. Consequently, beef cattle production in Chihuahua is cyclical, with the beginning and end of the cattle production year determined by the export season, which begins in August. In late summer, beef calves born the previous spring are exported to the United States for backgrounding and feeding in the U.S. beef industry. These animals typically weigh 300-400 pounds at export. The most common beef breeds in Chihuahua are Hereford, Angus, Limousin and Charolais. The exported cattle cannot be fattened or grown out in Mexico due to limited grain and forage supplies. Thus, the Chihuahua cattle industry exports large numbers of cattle to the United States. Of the 1.2 million beef animals exported to the United States from Mexico in 2003, 50% crossed at the Columbus and Santa Teresa, New Mexico and Presidio, Texas ports of entry (all of which border Chihuahua). The source of these cattle is primarily Chihuahua state, with some exported cattle originating in Durango state. Mexican exporters tend to send the majority of their annual calf crop into the United States; however, when the U.S. demand for feeder cattle contracts, there is usually a subsequent increase in the number of Mexican beef calves fed and marketed in Mexico.

Limited information is available about the Chihuahua export cattle sector, although cattle producers in Chihuahua are an integral part of the Southwest and overall U.S. cattle industries. Previous research at NMSU has examined the flow of cattle from Mexico into the United States and developed models for forecasting cattle imports (Mitchell et al. 2001; Mitchell 2000; Guinn and Skaggs 2005). Skaggs et al. (2004a, 2004b) used data provided by the Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua and the New Mexico Livestock Board to examine the Mexican origins and U.S. destinations of Mexican calves entering the United States at the Santa Teresa, NM port of entry. Earlier research at the Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua resulted in cost and return estimates and economic analysis of cattle production in Chihuahua (Martínez Nevarez 2002). Carmona and Skaggs (2006) described the procedures and requirements Chihuahua cattle producers must follow in order to export their calves to the United States. The survey results reported here provide additional insight into selected characteristics of beef cattle exporters in Chihuahua.

Methodology

Researchers at New Mexico State University and the Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua jointly designed a questionnaire administered to cattle exporters in Chihuahua. A Memorandum of Understanding exists between the two universities, although this was the first time the principal investigators had collaborated in a research effort. The survey of Chihuahua cattle exporters was funded by a Cooperative Agreement between the U.S. Department of Agriculture—Economic Research Service and New Mexico State University. The Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua received reimbursements for survey-related expenses through a sub-contracting agreement. The investigators primarily responsible for the survey instrument development were Cristina Carmona Martínez (New Mexico State University), Dr. Rhonda Skaggs (New Mexico State University) and M.C. Javier Martínez Nevarez (Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua).

The survey instrument was formulated to gather a broad range of data and information from cattle exporters. The data collected through the survey are reported in this paper. The instrument included questions related to the cattle exporters’ personal information, general cattle production information, the current cattle exportation process, genetic quality of the cattle, cattle identification systems used by producers, strength/weakness/opportunities/threats (SWOT) information, and information about the degree of enterprise diversification among the cattle exporters. The survey instrument and proposed research protocol were approved by NMSU’s College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences Survey Review Committee and the Institutional Review Board in early 2004. A copy of the survey instrument is presented in Appendix I.

Administration of the survey to cattle exporters in Chihuahua was conducted by students from both universities. Abelardo Díaz Samaniego (graduate student, UACh), Alan E. Alarcón (Junior, UACh), Federico Morales (Junior, UACh), Hazel Hoffman (Senior, UACh), Agustín Corral Luna (graduate student, UACh), and Cristina Carmona (graduate student, NMSU). All surveys were conducted using face-to-face interviews of cattle exporters. It is important to mention that it was necessary to drive long distances in Chihuahua in order to find the sampled cattle exporters. All of the students who helped with this study are natives of the Chihuahua counties (i.e., municipios) where the surveying was done. The face-to-face interviews were all conducted during the last week of May, the entire month of June, and the first week of July 2004. The most difficult part of the survey’s administration was finding cattle exporters in Chihuahua City because most of them have other cattle and non-cattle businesses or activities. Thus it was very difficult to find a mutually agreeable scheduled time and place to complete the survey instrument.

In addition, some counties in Chihuahua are located far away from Chihuahua City. Guerrero, Madera, Balleza, and Temosachi counties are situated 3-4 hours from Chihuahua City. A few days there were required to get a meeting with the sampled cattle producers. Also, some cattle producers do not live in towns; rather, they live on isolated ranches, and access to the ranches is not easy. Walking around the small towns where some producers were located, many local residents noticed the presence of the student interviewers, and there was extensive speculation about the project and the meetings with producers. This research project was a main concern during summer 2004 for many cattle producers in the regions where interviews were conducted. Once a survey had been completed by one producer in a community, the rest of the producers were aware of the research project. Some producers were distrustful of the research project and asked many questions about the purpose of the research, and why they were selected to be in the sample. The Chihuahua cattle producers were also very concerned about whether or not the information they provided to the student interviewers would be available to the government.

Most Chihuahua producers exporting cattle to the United States are popular and respected in their communities, and have spent many years buying cattle from smaller producers who do not personally export cattle. For smaller cattle producers in Chihuahua the main characteristic they look for in a good cattle buyer is the ability to pay for the cattle at the moment of sale. The students’ experiences interviewing the smaller cattle producers were interesting and informative. The smaller producers were humble, hard-working rural people and warmly welcomed the student interviewers.

The Sample

The Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua (UGRCh) provided a list of cattle producers who have exported cattle to the United States at least once during the last five years (2000-2004). This list or sampling frame had 503 exporters. A random sample of 215 cattle producers was drawn from the sampling frame. Due to lack of time and large distances between counties, 143 surveys were successfully completed. Again, all questionnaires were completed during face-to-face interviews. The respondents to the survey include individuals who produce and export their own cattle as well as people who buy cattle in small towns directly from small scale producers. These exporters do all the paperwork and processing necessary for exportation, but are not necessarily cattle producers. The survey respondents included several large scale producers who export only cattle produced by themselves.

Thirty Chihuahua counties are represented in this survey, of 67 total. One survey respondent operates primarily in one county located in Durango state. Some of the counties where the survey was conducted have more observations than other counties which may actually have more cattle exporters, and this outcome likely reflects difficulties in locating some of the sampled producers during the summer of 2004. In several cases, the cattle exporters’ families live in the large cities of Chihuahua, Juarez, or Cuauhtémoc, but the male heads-of-household live primarily at their ranches in the country. The UGRCh list of cattle exporters included contact information such as telephone number and physical address, but it was often difficult to locate the cattle producers.

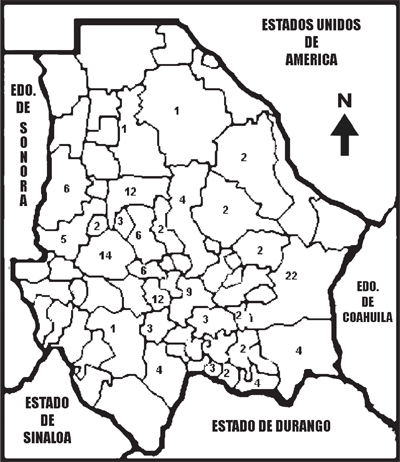

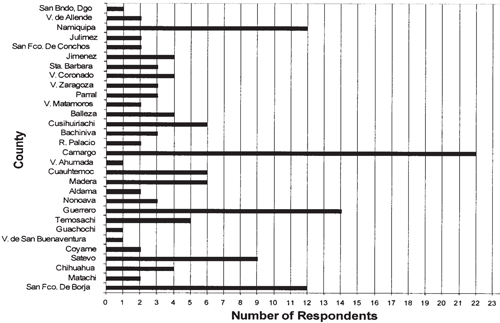

The number of survey respondents does not reflect the actual population of cattle producers in each county. Counties with the largest number of observations were Camargo, Cuauhtémoc, Cusihuiriachi, Guerrero, Madera, Namiquipa, San Francisco de Borja, Satevo and Temosachi. Figure 1 is a map of the distribution of the 142 survey respondents in Chihuahua state. Figure 2 shows the number of survey respondents in the counties where respondents were interviewed.

Figure 1. Map of distribution of survey respondents by county (n = 142).

Figure 2. Distribution of survey respondents by county (n = 143).

Survey Results

General Information about the Producer/Exporters

Most of the older survey respondents had only completed elementary school, although some did not complete elementary school (table 1). The respondents who have many decades of experience in exporting cattle to the United States (up to 50 years) had completed only elementary or middle school levels of education. Younger respondents tended to have completed high school, college and in a few cases graduate education. Almost 91% of the respondents were married (table 2). The 130 respondents who reported being married at the time of the survey also provided information about their spouse’s educational attainment (table 3). Spouses of the respondents tended to have levels of education similar to the survey respondents. Survey respondents were asked to self-assess their English speaking abilities (table 4). More than half of the producers rated their English ability as poor, while 41% said their English was fair or good, and almost 3% indicated their English skills were excellent.

Table 1. Educational attainment of survey respondents (n = 143).

| Education Level | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Elementary School | 23 | 16.08% |

| Middle School | 28 | 19.58% |

| High School | 44 | 30.76% |

| Undergraduate College | 42 | 29.37% |

| Graduate College Degree | 4 | 2.79% |

| Refused to Answer | 2 | 1.40% |

Table 2. Marital status of survey respondents (n = 143).

| Marital Status | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Single | 9 | 6.29% |

| Married | 130 | 90.91% |

| Widow | 2 | 1.40% |

| Refused to Answer | 2 | 1.40% |

Table 3. Spouse’s educational attainment (n = 130).

| Education Level | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Elementary School | 23 | 17.69% |

| Middle School | 29 | 22.31% |

| High School | 42 | 32.31% |

| College | 34 | 26.15% |

| Graduate | 2 | 1.54% |

Table 4. Survey respondents’ ability to speak English (n = 143).

| Ability to Speak English | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Poor | 78 | 54.54% |

| Fair | 40 | 27.97% |

| Good | 19 | 13.28% |

| Excellent | 4 | 2.79% |

| Refused to Answer | 2 | 1.40% |

Respondents’ Cattle Exporting and Marketing Practices

The surveyed cattle exporters (n = 143) reported an average of 18 years exporting cattle to the United States (table 5). Ninety percent of the respondents reported having last exported cattle to the United States during either 2003 or 2004. The remaining 10% reported they had last exported cattle to the United States in 2000, 2001, or 2002. The total number of years per individual reported for exporting cattle ranged from 1 to 60. In addition, the average age for the 141 respondents who gave their age was 47 years, with a range of 22 to 82 years. Several survey respondents described how once someone begins exporting cattle to the United States, more small cattle producers will sell their animals to that person. As time passes, the cattle exporter will create a good or bad reputation among the small producers, and only those exporters who earn and maintain a good reputation can continue in the cattle exporting business. In addition, a cattle exporting business is frequently maintained across generations, with one or more sons taking over a father’s business. Cattle exporting only was reported by 96.45% respondents, with 3.55% indicating they also exported horses to the United States.

Table 5. Survey respondents’ ages and years exporting to the United States (n = 143).

| Years | Years exporting cattle | Producer age | ||

| # Respondents | % Respondents | # Respondents | % Respondents | |

| ≤ 5 | 24 | 16.78% | — | — |

| 6 – 10 | 26 | 18.18% | — | — |

| 11 – 20 | 50 | 34.97% | — | — |

| 21 – 30 | 23 | 16.08% | 11 | 7.69% |

| 31 – 40 | 13 | 9.09% | 38 | 26.57% |

| 41 – 50 | 5 | 3.50% | 43 | 30.07% |

| >50 | 2 | 1.40% | 48 | 33.57% |

| Refused to answer | — | — | 3 | 2.10% |

| Mean response | 18 years | 47 years | ||

The survey respondents were asked the typical weights at which they export cattle to the United States (table 6). Almost 75% of the exporters typically shipped their calves into the United States at weights of less than 200 kilograms (440 pounds). Table 7 shows the distribution of annual cattle exports by the survey respondents. The respondents reported typical annual exports of cattle ranging from 30 to 3,000 animals, with an average export of 549 animals. Approximately 50% of the surveyed group said they annually exported between 101 and 500 calves.

Table 6. Estimated calf weight at time of export (n = 143).

| Typical exported calf weight (kilograms) | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| <141 (<311 pounds) | 2 | 1.39% |

| 141 – 160 (311-353 pounds) | 28 | 19.58% |

| 161 – 180 (355-397 pounds) | 50 | 34.96% |

| 181 – 200 (399-441 pounds) | 27 | 18.88% |

| 201 – 220 (443-485 pounds) | 6 | 4.19% |

| 221 – 240 (487-529 pounds) | 13 | 9.09% |

| 241 – 260 (531-573 pounds) | 12 | 8.39% |

| 261 – 280 (575-617 pounds) | 4 | 2.79% |

| >281 (>619 pounds) | 1 | 0.69% |

Table 7. Typical number of cattle exported annually by the survey respondents (n = 143).

| Cattle exported annually | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| ≤ 50 | 10 | 6.99% |

| 51 – 100 | 16 | 11.19% |

| 101 – 250 | 38 | 26.57% |

| 251 – 500 | 34 | 23.78% |

| 501 – 1,000 | 22 | 15.38% |

| 1,001 – 1,500 | 15 | 10.49% |

| 1,501 – 3,000 | 7 | 4.90% |

| No response | 1 | 0.70% |

| Average annual exports reported | 549 head |

Of the 143 respondents, 40 (27.97%) marketed some of their cattle in Mexico; however, 103 (72.02%) respondents did not market locally. Feeder cattle prices in Mexico are generally lower than in the United States because the Mexican feeding industry is not well developed, thus there is a strong incentive to export animals to the United States. Table 8 summarizes the reasons for not marketing feeder cattle in Mexico given by the 103 respondents who reported they did not sell domestically. Ninety-five percent of the respondents who didn’t market cattle in Mexico said there were “low prices in the local market, and better prices in the United States.” Small numbers of respondents reported that there was a high incidence of coyotaje in the local Mexican market. Coyotaje can be roughly translated as “ripoff.” In Mexico, it is not possible for large lots of cattle to be sold at the same time, while when exporting to the United States producers can market large numbers of cattle at once. Three respondents indicated that they preferred to market cattle in the United States because they were able to sell large lots of cattle there.

Table 8. Reasons for not marketing cattle in Mexico (n = 103).

| Reason | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Low prices at the local market | 98 | 95.14% |

| High incidence of coyotaje* | 2 | 1.94% |

| Difficult to sell the whole lot at one time in Mexico |

3 | 2.91% |

| *When producer receives less money for his cattle, with the buyer paying less in order to increase their profit margin. | ||

When asked their reasons for exporting cattle to the United States, 93.7% of the respondents cited “better prices in the United States” (table 9). A few respondents indicated that it was “impossible to market cattle in Mexico,” that it was simply their “tradition” to export cattle to the United States, or that it was difficult to sell a large lot of cattle in Mexico. Many producers are not financially capable of maintaining their cattle on their ranches because in the fall months, supplemental feeding is required after the grass supply has dried up. Many producers have no choice other than to quickly market their young calves in the fall before the cattle start losing weight. These producers will supplement only their breeding animals until the spring rainy season arrives. It is very characteristic of small Chihuahua cattle producers to follow this marketing pattern for their male calves and heifers. Some larger producer/exporters with greater financial resources have the capacity to feed their young animals for two or three fall months and then export them. In this system, the calves gain weight, and at the same time producers can wait for cattle prices go up.

Table 9. Reasons for not marketing cattle in Mexico (n = 143).

| Reason | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Better prices in the United States | 134 | 93.70% |

| Impossible to market cattle in Mexico | 5 | 3.49% |

| Tradition | 1 | 0.69% |

| Difficult to sell the whole lot in Mexico | 1 | 0.69% |

The survey respondents were asked about the origin of the cattle they export to the United States. It is not uncommon for some exporters to purchase small lots of calves (even individual animals) from small producers in order to form larger export lots. Table 10 summarizes the responses relating to the composition of export cattle lots. One third of the respondents reported exporting only animals that they produced, while the majority of respondents indicated they bought calves from other producers for export marketing. Approximately 15% of the respondents reported that they purchase 100% of their export calves from others.

Table 10. Composition of export cattle lots (n = 143).

| Percentage | Exported calves produced by respondent |

Exported calves purchased from other producers |

||

| # Respondents | % Respondents | # Respondents | % Respondents | |

| 0% | 22 | 15.38% | 47 | 32.87% |

| 1 – 10% | 20 | 13.99% | 2 | 1.40% |

| 11 – 30% | 24 | 16.78% | 9 | 6.30% |

| 31 – 50% | 17 | 11.89% | 13 | 9.09% |

| 61 – 80% | 10 | 7.00% | 28 | 19.58% |

| 81 – 99% | 3 | 2.10% | 22 | 15.38% |

| 100% | 47 | 32.87% | 22 | 15.38% |

Chihuahua cattle exporters incur several costs when exporting cattle to the United States. These expenses include costs of inspection, permits, taxes, and transportation from their ranch to the U.S.–Mexico border. Table 11 summarizes their responses. The mean cost of exporting was 327 pesos/head, although the respondents reported a wide range of costs, depending on ranch location and other factors. Their last price received for calves exported to the United States was also provided by the respondents. A base weight of 300 pounds was used as a benchmark weight, even though not all producers exported animals weighing 300 pounds. These responses are presented in table 12.

Table 11. Respondents’ reported average cost (in pesos) of exporting a calf to the United States (n = 143).

| Cost of export per animal (pesos) | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| 170 – 200 | 8 | 5.59% |

| 220 – 250 | 10 | 6.99% |

| 260 – 280 | 5 | 3.50% |

| 281 – 300 | 31 | 21.68% |

| 301 – 320 | 5 | 3.50% |

| 330 – 340 | 30 | 20.98% |

| 350 – 370 | 18 | 12.59% |

| 371 – 399 | 19 | 13.29% |

| 400 – 460 | 9 | 6.29% |

| 500 | 1 | 0.70% |

| No response | 7 | 4.90% |

| Mean response | 327 pesos |

Table 12. Respondents’ reported last average price ($/pound) received for cattle exported to the United States, base weight 300 pounds/animal (n = 143).

| Price ($ / pound) | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| < $1.00 | 2 | 1.40% |

| $1.00 – $1.19 | 23 | 16.08% |

| $1.20 – $1.29 | 40 | 27.97% |

| $1.30 – $1.39 | 58 | 40.56% |

| $1.40 – $1.45 | 19 | 13.29% |

| No response | 1 | 0.70% |

| Mean response | $1.27 |

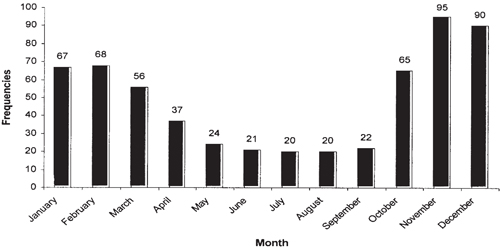

The season of cattle exporting is determined primarily by seasonal rainfall patterns. As soon as the first low temperatures occur in the fall months, forage quality is reduced and calves start to lose weight. Thus, cattle exports increase in the fall. Figure 3 shows the preferred months for exporting as reported by the survey respondents. The bars in figure 3 are labeled with the numbers of respondents who indicated they preferred to export in those months, with all 143 respondents reporting at least one preferred month.

Figure 3. Survey respondents’ preferred months for exporting cattle to the United States (n = 143, more than one response per respondent was possible).

Culled cattle are often marketed or sent to auction locally near a producer’s home ranch. Information reported by the respondents about marketing of culled cattle is presented in table 13. Almost half of the respondents indicated they send the culled animals to auction in Chihuahua City or other locations.

Table 13. Respondents’ marketing of culled cattle (n = 143).

| Marketing method | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| At the U.S.–Mexico ports of entry | 23 | 16.08% |

| At the ranch | 29 | 20.28% |

| At gathering points off the ranch | 16 | 11.19% |

| Auction in Chihuahua City | 43 | 30.07% |

| Other auctions | 27 | 18.88% |

| No response | 5 | 3.50% |

Ports-of-Entry Used to Export Cattle

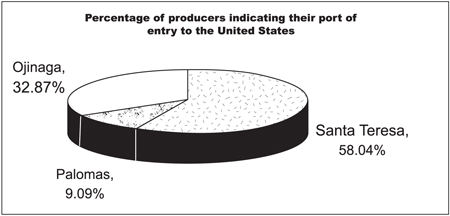

New Mexico hosts the largest and most modern livestock import and export facilities on the U.S.–Mexico border (i.e., the Santa Teresa, NM–San Jerónimo, Chihuahua facility). Almost a fourth of all cattle imported in 2003 from Mexico were processed at the Santa Teresa, NM–San Jerónimo, Chihuahua port-of-entry. The Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua operates both sides of the Santa Teresa–San Jerónimo facility. This port-of-entry’s livestock handling facilities offer practical and economic advantages; livestock is penned and processed at the border, then walked into the United States, thus saving time and costs and minimizing the animals’ weight losses. In addition, animals are exposed to less stress than at any other cattle crossing facility on the U.S.–Mexico border. The survey respondents were asked to name the port-of-entry they typically use for exporting cattle from Mexico into the United States (figure 4). The port of Palomas, Chihuahua is the Mexican counterpart of the Columbus, NM port, and is located in Luna County, New Mexico. Ojinaga, Chihuahua is the Mexican counterpart of the Presidio, TX port-of-entry.

Figure 4. Ports of entry used by producers to cross their animals into the United States (n = 143).

Several reasons were given by the survey respondents for using a specific port-of-entry (table 14). The primary reason given was the location of a port-of-entry relative to an exporter’s ranch or livestock holding facilities, followed by better infrastructure at a particular border crossing. The preference for the Santa Teresa border crossing (n = 83) also reflects the geographic distribution of survey respondents throughout Chihuahua and their proximity to Santa Teresa, NM. Consequently, the border crossing most frequently cited by the respondents was Santa Teresa, NM. Some producers for whom Santa Teresa is not the border crossing closest to their ranch preferred to use Santa Teresa because they believed less shrinkage of their animals and less weight loss would occur during the exporting process. Some producers indicated that access to Santa Teresa was easier for them, and that Santa Teresa offered them the best service and the best administrative personnel relative to other border crossings.

Table 14. Respondents’ preferred border crossing for exporting cattle, and reasons for the preference (n = 143).

| Reason | Santa Teresa, NM / San Jerónimo, Chih. |

Columbus, NM / Palomas, Chih. |

Presidio, TX / Ojinaga, Chih. |

|||

| # Respondents |

% Respondents |

# Respondents |

% Respondents |

# Respondents |

% Respondents |

|

| Is the border crossing closest to the ranch | 38 | 45.78% | 3 | 23.08% | 47 | 100% |

| Border crossing has better infrastructure | 18 | 21.69% | ||||

| Border crossing has better highway access | 15 | 18.07% | ||||

| A large number of cattle buyers are located there | 6 | 7.23% | 2 | 15.38% | ||

| The prices offered there are better than any other border crossing | 6 | 7.23% | ||||

| Less cattle weight loss | 3 | 23.08% | ||||

| Service is better & export process is easier | 2 | 15.38% | ||||

| Buyer is located there | 3 | 23.08% | ||||

The Columbus, NM–Palomas, Chihuahua border crossing was preferred by a small number of exporters (n = 13). Those indicating a preference for Columbus–Palomas indicated that they believed there was less shrinkage of the animals as a result of using that port, or that they had established buyers who were located at Columbus–Palomas. Preferences for the Presidio, TX–Ojinaga, Chihuahua port (n = 47) were based on its geographical location.

Reasons for Involvement in Livestock Industry

For most of the cattle exporters interviewed, the strongest reason for being in the livestock industry was “tradition” (table 15). In Chihuahua, to be a part of the cattle industry means you can be proud, you are a hard worker, and you are respected. Many cattle producers in Chihuahua have other businesses or activities from which they derive more income, but for them it is very important to continue being a part of the state’s livestock industry. Being in the cattle industry gives them a special status in Chihuahua society. Chihuahua state is recognized throughout Mexico as “cattle country,” and a large producer of beef.

Table 15. Respondents’ reasons for being in the cattle industry (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Reason | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Is an activity that they have been doing since they were a child |

24 | 16.78% |

| Tradition | 82 | 57.34% |

| They “like” being in the cattle industry | 24 | 16.78% |

| They “love” the cattle industry | 5 | 3.50% |

| Livestock is profitable | 27 | 18.88% |

Attitudes toward the North American Free Trade Agreement

When questions about the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) were posed to the survey respondents, 41% of them indicated that NAFTA has had a negative impact on the livestock industry in Chihuahua (table 16). Generally speaking, these respondents tended to believe that Mexico is not in a condition to compete with wealthy countries such as the United States and Canada. As a result, they believe products coming from the United States and Canada will invade the Mexican market and domestic producers will be negatively affected by this situation. Alternatively, 32% of the respondents think that NAFTA will help Mexico develop because the high quality standards which exist in the United States and Canada will encourage economic progress in Mexico. Finally, 21% of the people surveyed said that NAFTA has not impacted the Chihuahua livestock industry.

Table 16. Cattle exporters’ opinions about NAFTA’s impact on the Chihuahua cattle industry (n = 143).

| NAFTA’s Impact | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Positive impact | 46 | 32.17% |

| Negative impact | 59 | 41.26% |

| No impact | 31 | 21.68% |

| Unaware of NAFTA | 4 | 2.80% |

| No response | 3 | 2.10% |

Problems Experienced in the Cattle Export Process

Survey respondents were asked about difficulties they have experienced in the process of exporting cattle from Mexico to the United States (table 17). The respondents indicated that sanitary requirements, customs procedures, and excess bureaucracy have been problematic, although they did not distinguish between U.S. and Mexican requirements or procedures. More than half of the respondents reported that cattle buyers often try to pay prices that are too low.

Table 17. Difficulties experienced in the export process (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Difficulties | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Many sanitary requirements | 75 | 52.44% |

| Excessive customs procedures | 36 | 25.17% |

| “Coyotaje” of the cattle buyers | 74 | 51.74% |

| Bureaucracy in the livestock organizations | 30 | 20.97% |

| Bureaucracy in the government agencies involved in exporting |

35 | 24.47% |

| American sanitary inspection requirements | 49 | 34.26% |

| Language barrier | 11 | 7.69% |

Perceptions of the Future of Domestic and Export Cattle Markets

Questions were asked regarding the respondents’ perceptions of the future of cattle exports to the United States and the future of the domestic Mexican cattle market. The most frequent responses to these questions are shown in table 18. Generally, they observed that throughout recent years more and more requirements for export have been imposed on Mexican cattle due to animal health or sanitary concerns, and the respondents expect more sanitary regulations or barriers in the future. The producers also believed that there would be continued instability in export market cattle prices. One third of the respondents believed that the export market will continue to become more specialized in terms of the types of cattle demanded by U.S. importers. Almost 29% of the respondents believed that the export market will continue to grow in the future.

Table 18. Respondents’ perceptions of the futures of cattle exporting and the domestic Mexican cattle market (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Perception of cattle exporting future | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| More sanitary barriers to export | 90 | 62.94% |

| Price instability | 89 | 62.24% |

| Market specialized in terms of cattle demanded | 47 | 32.87% |

| Growing market | 41 | 28.67% |

| More price stability | 13 | 9.09% |

| Perception of national market’s future | ||

| Market dependent on imports | 61 | 42.65% |

| More vertically integrated market | 56 | 39.16% |

| Market differentiated by cattle and beef quality | 54 | 37.76% |

| Growing market | 52 | 36.36% |

| Market constrained because of poor Mexican economy | 43 | 30.06% |

In terms of the Mexican national market, 42.65% of the respondents believed that the future of the Mexican market for beef will be dependent on imports because Mexico is not able to be self-sufficient in beef production. Almost 40% of the producers believed that the Mexican national market will be increasingly characterized by vertical integration and that the Mexican market for beef and cattle will be further differentiated by quality. Approximately one-third of the respondents believed the Mexican market for beef and cattle will grow, while 30.06% indicated that they think the Mexican national market will be constrained because of limited economic growth.

Government Program Participation

The Mexican government has several programs which subsidize cattle producers. Genetic improvement programs provide subsidies to cattle producers to help them buy breeding bulls and heifers at lower prices. The state and federal governments each contribute 50% of the total cost of the subsidy, and producers pay the remainder. PROGAN is a direct payment per head for mature cows and bulls which is paid to cattle producers on the condition that they apply improvements to their ranches such as soil conservation practices. Finally, producers receive direct payments to compensate for the effects of drought. This payment is based on the number of hectares. Table 19 shows the survey respondents’ usage of these government programs.

Table 19. Survey respondents’ participation in government subsidy programs for the livestock industry (n = 143).

| Governmental programs used by respondent? | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Yes | 114 | 79.72% |

| No | 29 | 20.27% |

| Difficulties experienced with the government programs? | ||

| Yes | 40 | 27.97% |

| No | 79 | 55.24% |

| Refused to answer | 24 | 16.78% |

| Government programs used by the respondents (more than one response per respondent was possible) | ||

| Genetic improvement program | 93 | 65.03% |

| PROGAN | 71 | 49.65% |

| Drought assistance program | 33 | 23.07% |

| Tuberculosis and/or brucellosis testing | 15 | 10.49% |

| Pasture improvement program | 10 | 6.99% |

Almost 80% of the respondents had received government subsidies, and 55.24% said they had experienced no problems with government programs. Almost two-thirds of the respondents had purchased bulls or breeding heifers with the assistance of government subsidies.

The respondents gave a variety of answers when asked their opinions of what they would like to see the Mexican federal government do to improve the cattle exporting process (table 20). Better provision of information about the international cattle market was listed as the top priority for 55.94% of the respondents, while 52.45% indicated they wanted the federal government to simplify the export paperwork process. Approximately 46% stated that they wanted the government to restrict the entrance of cattle from other Mexican states into Chihuahua.

Table 20. Cattle exporters’ recommendations for what the Mexican federal government can do to improve the cattle exporting process (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Preferences | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Provide assistance to cattlemen’s organizations to improve & modernize export infrastructure. |

95 | 66.43% |

| Provide Mexican livestock industry with better information about international cattle markets. |

80 | 55.94% |

| Simplify the export paperwork process. | 75 | 52.45% |

| Restrict the entry of cattle from other Mexican states. | 66 | 46.15% |

| Create a more efficient internal cattle inspection process. | 62 | 43.36% |

| Other | 7 | 4.90% |

With respect to the types of government assistance they believe would help them personally, 83.92% of the respondents expressed a preference for improved preconditioning infrastructure (table 21). The cattle exporters are very interested in improving the quality of their export animals, in order to make them more competitive and more desirable to the U.S. market. Seventy percent of the respondents stated that they would like to see more government support for genetic improvement of cattle, and 51.75% expressed a preference for the creation of government programs that would provide incentives for the development of vertically integrated livestock-oriented companies. These preferences show the desire of the Chihuahua cattle industry to increase the value of their industry and its products.

Table 21. Cattle exporters’ preferences for government assistance to the Mexican livestock industry (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Preferences | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Subsidies for creation of infrastructure for use in preconditioning calves prior to export. |

120 | 83.92% |

| Increased assistance for genetic improvement of cattle. | 101 | 70.64% |

| Creating incentives for vertically integrated livestock oriented companies. |

74 | 51.75% |

| Mechanisms for risk management. | 57 | 39.86% |

| Increased tuberculosis eradication efforts. | 53 | 37.06% |

| Other | 3 | 2.10% |

Respondents’ Evaluation of Their Cattle

The survey respondents were asked to use a scale measure (ranging from 1 to 10, 10 being the highest score) to evaluate their cattle relative to similar cattle in the United States, particularly in terms of breeding quality. The respondents generally gave high scores to their cattle and tended to be very proud of their cattle (table 22). They reported that in terms of genetic quality, their animals are almost the same as U.S. cattle, because they have brought breeding animals from the United States and Canada.

Table 22. Score given by survey respondents to their cattle (n = 143).

| Score | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| <5 | 3 | 2.10 |

| 6 – 7 | 24 | 16.78 |

| 8 – 10 | 114 | 79.72 |

| No response | 2 | 1.4 |

Modern Cattle Management Practices

In Chihuahua state, practices such as artificial insemination and embryo transfer are becoming more common and important; however, those practices are possible only for large, well-financed cattle producers. The survey respondents’ use of several management practices is reported in table 23. The big producers generally sell breeding animals also, thus it is important for them to implement new management techniques in order to improve their production systems. For smaller producers those herd improvement practices are not achievable due to limited financial resources.

Table 23. Management practices used by survey respondents to improve cattle quality (n = 143); more than one response per respondent was possible.

| Management practices to improve the cattle quality |

# Respondents | % Respondents |

| Artificial insemination | 28 | 19.58% |

| Embryo transfer | 3 | 2.09% |

| Pregnancy detection | 74 | 51.74% |

| Fertility tests | 81 | 56.64% |

| Supplemental feeding of breeding stock | 91 | 63.63% |

| Supplemental feeding of calves prior to weaning | 56 | 39.16% |

| Feeder calf preconditioning | 110 | 76.92% |

Almost 20% of the respondents reported using artificial insemination, while only 3.09% indicated they currently practiced embryo transfer. Pregnancy detection and fertility testing are practiced by more than 50% of the respondents. Almost two-thirds of the respondents indicated they gave supplemental feed to their breeding animals (bulls and cows), but only 39.16% provided supplemental feed to their calves prior to weaning. Almost 77% preconditioned their calves prior to marketing.

Imports of Cattle from Central and Southern Mexico

During months or periods when there is a scarcity of calves in Chihuahua, the possibility of exporting year-round is of interest to cattle producer/exporters in Chihuahua. Some survey respondents said they had considered bringing animals from central and southern Mexico with plans to ultimately export those cattle or their offspring (table 24). The main reason for their interest in this activity is because cattle in central and southern Mexico are relatively cheap. However, these cattle are considered to be of low genetic quality compared to the cattle produced in the northern Mexican states near the U.S. border. In addition, animal health (i.e., sanitary) regulations in Chihuahua state currently do not permit cattle to come into Chihuahua from many other Mexican states.

Table 24. Survey respondents’ interest in bringing calves and heifers into Chihuahua from central and southern Mexico (n = 143).

| Interested in bringing cattle from central and southern Mexico? |

# Respondents | % Respondents |

| Yes | 35 | 24.48% |

| No | 104 | 72.73% |

| No response | 4 | 2.80% |

Breeding Animal Acquisitions and Genetic Quality

The Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua organizes a large sale of locally produced bulls once a year. This activity is part of the Genetic Improvement Program (table 19). In this program, the producer has to pay 40% of the total cost of the bull, and the federal and state governments cover the remaining 60%. However, producers have another alternative, which is to buy foreign-produced breeding animals (bulls, heifers and/or mature cows). Frequently, marketing specialists from states such as New Mexico, Texas and Oklahoma work through the Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua to offer breeding cattle to producers. There are numerous one-on-one contacts between Chihuahua producers and producers of breeding animals in the United States.

Foreign-produced breeding animals are often preferred because they are priced lower than animals produced on local ranches. But, sometimes the animals coming from the United States are not proven or their genetic quality is considered inferior for the U.S. market. Consequently, some foreign-produced breeding animals have been sold using a Mexican meat price rather than a higher breeding stock price.

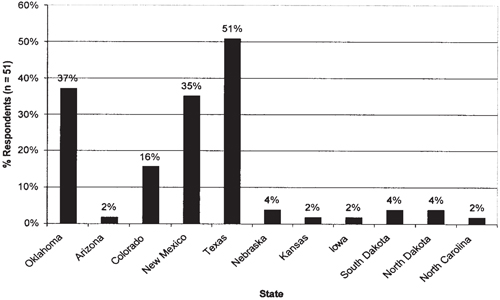

Fifty-one of the survey respondents had bought breeding animals in the United States (table 25); this represents 35.66% of the surveyed group. Figure 5 shows the distribution of breeding cattle purchases by U.S. state (for the 51 respondents who had bought breeding animals in the United States). The respondents who reported importing breeding cattle from the United States indicated they had done so because the imported cattle were of better genetic quality and sold at a better price than domestically-produced breeding cattle. Almost 58% of the respondents who had imported breeding animals from the United States reported having done so since 2000, while other respondents reported imports as far back as 1980.

Table 25. Survey respondent’ purchases of breeding cattle (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Breeding cattle purchases? | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Breeding cattle acquired in the United States | 51 | 35.66% |

| Breeding cattle acquired in another Mexican state and brought into Chihuahua |

30 | 20.98% |

| Breeding cattle exchanged locally with other Chihuahua producers |

77 | 53.85% |

| Breeding cattle acquired from Canada | 13 | 9.09% |

Figure 5. U.S. states from where survey respondents have purchased breeding cattle (n = 51; more than one response per respondent was possible).

Nine percent of the survey respondents reported purchasing breeding cattle from Canada. Almost 21% of the survey respondents said they had brought breeding cattle into Chihuahua from another Mexican state, while a majority had bought or exchanged breeding cattle locally, in Chihuahua. The Mexican states reported most frequently as sources of breeding cattle were Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas and Coahuila.

A large majority of the survey respondents believed that the genetic quality of animals exported from Chihuahua to the United States was getting better every year (table 26). The cattle exporters attribute the improvement to the use of U.S.-produced breeding animals, and to high-quality locally-produced breeding animals. Additionally, the survey respondents credited government-subsidized genetic improvement efforts with helping small producers obtain high genetic quality bulls and/or heifers.

Table 26. Survey respondents’ perception of the genetic quality of Chihuahua cattle exported to the United States (n = 143).

| Has the genetic quality of exported Chihuahua cattle improved in recent years? |

# Respondents | % Respondents |

| Yes | 134 | 93.71% |

| No | 7 | 4.90% |

| No response | 2 | 1.40% |

Animal Identification Systems

The animal identification system used in Chihuahua state is a combination of ear notching, hot branding, and eartags (table 27). Slightly more than half of the survey respondents reported that they used all three identification methods. Small producers frequently used only ear notching and hot branding. Traditionally, producers only work their cattle once a year to establish animal identification. In the months from August to December producers identify new male and heifer calves, spay and castrate the calves, and prepare them to be exported. Producers believe ear notching and hot branding to be the two most convenient animal identification methods. Once a cattle herd is worked in the late summer or fall, many producers are no longer concerned about animal identification. Producers who keep performance information for each animal also use hot branding and eartags, and will occasionally use tattoos.

Table 27. Systems of animal identification used by survey respondents (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Identification method | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Hot brand, ear tag, ear notching (all used together) |

74 | 51.75% |

| Hot brand | 65 | 45.45% |

| Ear tag | 39 | 27.27% |

| Ear notching | 22 | 15.38% |

| Tattoo | 1 | 0.70% |

Recently, U.S. firms have been trying to sell animal identification systems incorporating global positioning system (GPS) technology to Chihuahua cattle exporters. Table 28 shows the results for a survey question that asked whether or not the survey respondents were aware of and/or interested in using the GPS-based animal identification technology. There have been numerous seminars and presentations in Chihuahua giving producers general information about these identification systems (how they work, costs of implementation and operation, etc). Some of this information has been made available through the Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua. The survey found that approximately half of the respondents had heard about the GPS-based animal identification technology, and that slightly more than half were thinking about adopting the technology.

Table 28. Survey respondents’ awareness of and intentions to use GPS-based animal identification technology (n = 143).

| Aware of GPS technology? | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Yes | 74 | 51.75% |

| No | 68 | 47.55% |

| No response | 1 | 0.70% |

| Thinking about using GPS technology? | ||

| Yes | 76 | 53.15% |

| No | 62 | 43.36% |

| No response | 6 | 4.20% |

Mexican producers believe that additional requirements will be necessary to export cattle to the United States in the future, and implementation of GPS-based animal identification technology may be required. The typical cattle producer in Chihuahua is cautious about applying new technology in their production system, but in general they consider that any technology or management practice that improves the livestock industry must be considered. Cattle producers will need to consider different factors when they make decisions about adopting GPS-based animal identification technology. Table 29 is a summary of the factors that the survey respondents said would be important in their future decisions about GPS-based animal identification technology.

Table 29. Factors survey respondents will consider with respect to GPS-based animal identification technology (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Factor to be considered | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Initial investment | 56 | 39.16% |

| Annual operation cost | 36 | 25.17% |

| Benefits of the technology | 49 | 34.27% |

| Required infrastructure | 27 | 18.88% |

| Availability and cost of technical support | 34 | 23.78% |

Sources of Information

Many sources of information are available to cattle producers in Chihuahua state. In most counties the Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua has local branches which provide services and information to members. This organization is not a government agency, and was created by producers in order to serve them and help them with export procedures and other activities. In addition, there is an informational magazine produced by the Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua in coordination with specialists in ruminant nutrition, reproduction and genetics, pasture and water resource management, and other topics. Cattle producers use this magazine to learn about new products available to livestock producers and general useful information. Table 30 summarizes the survey respondents’ common sources of information about technology and the cattle export process. The primary source of technology information reported by the survey respondents was magazines (primarily the Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua publication). The majority of producers also said the Unión was their principal source of information about the cattle export process. Forty-four percent of the respondents reported they had contact with cattle producers outside of Mexico, and 53.85% indicated that they regularly attend educational programs, congresses, or symposia dealing with agriculture.

Table 30. Survey respondents’ most common sources of information for technological improvements and the cattle export process (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Sources of information about technological improvements |

# Respondents | % Respondents |

| Specialized magazines | 103 | 72.02% |

| Newspaper | 14 | 9.79% |

| Internet | 4 | 2.79% |

| Research reports | 9 | 6.29% |

| Friends, informal meetings | 13 | 9.09% |

| Sources of information about the cattle export process | ||

| Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua | 104 | 72.73% |

| Local cattle producer associations | 36 | 25.17% |

Economic Diversification

For many Chihuahua cattle producers the livestock industry is one of many business activities they engage in, and for some producers their involvement in the cattle industry is primarily a hobby. These producers have other businesses or jobs, which they use to support their cattle production activities. They are motivated by strong traditions and a love of the rural life. Most small cattle producers produce cattle for a living. In the survey research reported here, 40.56% of the respondents have business activities other than cattle exporting or production. These businesses were primarily agriculturally oriented and included breeding cattle production, crop and/or fruit production. Almost 26% of the survey respondents reported that they have businesses that are unrelated to their agricultural sector businesses while 74.13% have only agriculturally-based businesses. These results are presented in table 31.

Table 31. Economic diversification of survey respondents (n = 143).

| Economic activity of survey respondent? | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Only cattle production | 85 | 59.44% |

| Other agricultural businesses or enterprises | 58 | 40.56% |

| Economic activity outside of the agricultural sector? | ||

| Yes | 37 | 25.87% |

| No | 106 | 74.13% |

Technology Available on Respondents’ Ranches

The survey respondents were asked to provide a brief inventory of the technological assets they currently have available on their ranches (table 32). This information provides some insight into the level of investment that has been made by the cattle producer/exporters and the types of technologies currently used on their ranches. Less than half of the survey respondents reported having electricity at their ranch or having a mobile telephone. Only 7.69% reported having a computer, while 14.69% said they had a land-line telephone at their ranch. Wells with pumps were reported by almost 60% of the respondents, and almost two-thirds said they had a tractor, tractor-operated agricultural implements, and cattle scales. Respondents also reported arroyos, rivers, and springs as water sources on their ranches. The presence of corrals or holding pens was reported by 93.01% of the respondents, while squeeze chutes were used by 79.72% of the respondents.

Table 32. Survey respondents’ technological assets currently in use (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Technological asset | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Electricity | 66 | 46.15% |

| Computer | 11 | 7.69% |

| Telephone (land line) | 21 | 14.69% |

| Mobile telephone | 67 | 46.85% |

| Well with pump | 83 | 58.04% |

| Tractor | 96 | 67.14% |

| Implements (use with tractor) | 88 | 61.53% |

| Corrals and holding pens | 133 | 93.01% |

| Squeeze chute | 114 | 79.72% |

| Cattle scales | 96 | 66.13% |

Grazing Resources

The survey respondents were asked to provide an estimate of the total amount of grazing land that they had in use by their cattle herds (table 33). Only seven respondents (4.90%) reported having less than 247 acres (100 hectares) of grazing land. The number of non-responses to this question reflects some producers’ unwillingness to give information about the quantity of land they use for grazing.

Table 33. Grazing land (in acres) used by survey respondents (n = 143).

| Acres grazing land | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| < 247a | 7 | 4.90% |

| 247 – 1,235.5b | 30 | 20.98% |

| 1,235.5 – 2,471c | 14 | 9.79% |

| 2,471 – 5,482d | 17 | 11.89% |

| 5,482 – 12,355e | 25 | 17.48% |

| > 12,355f | 33 | 23.08% |

| No response | 17 | 11.88% |

| a = <100 hectares, b = 100–500 hectares, c = 500–1,000 hectares, d = 1,000–2,000 hectares, e = 2,000–5,000 hectares, f = >5,000 hectares. |

||

Cattle Inventory and Production Information

The surveyed cattle exporters were asked to provide information about their cattle inventories at the time of the survey. Mother cow inventories are reported in table 34. Sixteen percent of the respondents reported holding no mother cows, while 25.88% indicated a cow inventory of less than 100 animals. With respect to heifer inventories (table 35), 57.34% reported less than 100 animals. The relatively large number (27.27%) of respondents reporting that they had no 2- to 3- year old heifers at the time of the survey likely indicates the higher-than-normal exports of young heifers to the United States which have occurred in recent years. Bull inventories vary greatly among the respondents (table 36), and ranged from zero to more than thirty animals.

Table 34. Mother cow inventory reported by respondents (n = 143).

| # Mother cows | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| 0 | 23 | 16.08% |

| 20 – 49 | 17 | 11.89% |

| 50 – 99 | 20 | 13.99% |

| 100 – 199 | 21 | 14.69% |

| 200 – 299 | 21 | 14.69% |

| 300 – 499 | 29 | 20.28% |

| ≥ 500 | 12 | 8.39% |

Table 35. Heifer (2 -3 years old) inventory reported by respondents (n = 143).

| # Heifers | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| 0 | 39 | 27.27% |

| 4 – 15 | 24 | 16.78% |

| 20 – 29 | 13 | 9.09% |

| 30 – 39 | 9 | 6.29% |

| 40 – 59 | 19 | 13.29% |

| 60 – 79 | 11 | 7.69% |

| 80 – 99 | 6 | 4.20% |

| 100 – 149 | 16 | 11.19% |

| ≥ 500 | 6 | 4.20% |

Table 36. Bull inventory reported by respondents (n = 143).

| # Bulls | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| 0 | 23 | 16.08% |

| 1 – 3 | 28 | 19.58% |

| 4 – 6 | 19 | 13.29% |

| 7 – 10 | 11 | 7.69% |

| 11 – 15 | 16 | 11.19% |

| 16 – 20 | 15 | 10.49% |

| 21 – 30 | 18 | 12.59% |

| ≥ 31 | 13 | 9.09% |

Calving percentages of at least 80% were reported by 36.36% of the respondents (table 37). Weaning percentages of at least 80% were reported by 37.07% of the respondents. When questioned about overall death losses in their herds, 40.56% of the surveyed exporters declined to respond (table 38). The large numbers of non-responses to these three performance-related questions again reflect the respondents’ desire to not divulge extensive personal information.

Table 37. Calving and weaning percentages reported by respondents (n = 143).

| Calving percentage | Weaning percentage | |||

| # Respondents | % Respondents | # Respondents | % Respondents | |

| ≤ 50% | 6 | 4.20% | 9 | 6.29% |

| 60 – 65% | 11 | 7.69% | 9 | 6.29% |

| 70 – 75% | 44 | 30.77% | 26 | 18.18% |

| 80 – 85% | 38 | 26.57% | 20 | 13.99% |

| 90 – 95% | 10 | 6.99% | 20 | 13.99% |

| 96 – 100% | 4 | 2.80% | 13 | 9.09% |

| No response | 30 | 20.98% | 46 | 32.17% |

Table 38. Total death losses reported by respondents (n = 143).

| Total death loss | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| 1% | 21 | 14.69% |

| 2% | 33 | 23.08% |

| 3 – 4% | 17 | 11.89% |

| 5% | 11 | 7.69% |

| ≥ 7% | 3 | 2.10% |

| No response | 58 | 40.56% |

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT)

Questions on the survey instrument asked the cattle producer/exporters to outline the current strengths of, weaknesses of, opportunities for, and threats facing the Chihuahua cattle export sector. Their responses are summarized in tables 39–42. The survey respondents reported that their cattle’s genetic quality was strong, and that cattle exports were a good source of income for Chihuahua producers. Almost half said that a strength of the Chihuahua cattle industry was the vast amounts of land which were available for cattle production.

Table 39. Strengths of the livestock industry in Chihuahua state, according to respondents (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Strengths | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Genetic quality of cattle | 88 | 61.54% |

| Cattle exports are a good source of income | 73 | 51.05% |

| Large expanses of land available to the livestock industry |

71 | 49.65% |

| Integration of the crop production into livestock production systems |

30 | 20.98% |

| High forage value of native grass species | 12 | 8.39% |

| Government programs to assist development of the livestock sector |

8 | 5.59% |

| Availability of livestock production technology | 3 | 2.10% |

Table 40. Weaknesses of the livestock industry in Chihuahua state, according to respondents (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Weaknesses | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Overgrazing of rangelands | 91 | 63.64% |

| Little profitability in cattle production | 53 | 37.06% |

| Resistance of producers to adopt new technologies |

29 | 20.28% |

| Producers are held captive by the U.S. export market |

28 | 19.58% |

Table 41. Opportunities for the livestock industry in Chihuahua state, according to respondents (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Opportunities | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| Geographic nearness to the United States | 115 | 80.42% |

| Possibilities for diversifying production | 48 | 33.57% |

| Sale of breeding cattle to other Mexican states | 41 | 28.67% |

Table 42. Threats facing the livestock industry in Chihuahua state, according to respondents (n = 143; more than one response per respondent was possible).

| Threats | # Respondents | % Respondents |

| U.S.–Mexico border closures | 107 | 74.83% |

| Persistent droughts | 97 | 67.83% |

| High costs of agricultural inputs | 36 | 25.17% |

Almost two-thirds of the respondents indicated that overgrazing was a serious weakness of their industry, while a third said cattle production was not profitable. Almost 20% of the producer/exporters said that a weakness of their industry was that it was “captive” to the U.S. export market.

Eighty percent of the producer/exporters said that their nearness to the U.S.–Mexico border was an opportunity for Chihuahua’s cattle industry. Seventy-five percent of the survey respondents said that future closures of the U.S.–Mexico border to cattle exports was a threat, and 67.83% reported that persistent drought threatens the Chihuahua cattle industry.

Conclusion

The livestock industry in Chihuahua is primarily a cow–calf production system operating in land-extensive conditions. The traditional market for Chihuahua cattle producers has been export of steer and spayed heifer calves to the United States. Extended drought periods during the last decade have negatively affected the Chihuahua livestock industry and the state’s cattle inventory has been reduced as a consequence. Improvements in Chihuahua’s livestock sector have been occurring for many years with the entry into Chihuahua of breeding animals from the United States and the intervention of the Mexican government with subsidies for cattle producers. It is also important to point out that recent changes in export procedures required by both the Mexican and U.S. governments have forced Mexican producers to be more well-organized and competitive.

The exporters’ perceptions of the cattle export market gives an idea of how they manage to survive in this dynamic market, which changes rapidly according to international and domestic events. Past changes in the export market have forced members of the Mexican cattle industry to learn how to adapt to new and continuously changing rules and regulations. The cattlemen’s organizations (i.e., the Unión Ganadera Regional de Chihuahua and county-level producer associations) are working to help producers and exporters learn about and adapt to regulations made by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Mexican government.

For many Mexican cattle producers, particularly those in Chihuahua state, exporting feeder calves to the United States is part of their identity. The export market is a strong tradition that extends through multiple generations of Chihuahua cattle ranchers. Some exporters see potential growth in demand for feeder cattle by the domestic Mexican market, with potential for increases in cattle feeding within Mexico. But, the cattle exporters tend to be skeptical that the domestic Mexican market can compete with the higher calf prices offered by U.S. cattle feeders. Many of the surveyed individuals believe the future of Mexican cattle exports to the United States will involve more and more animal health or sanitary regulations established by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (and potential border closures as a result of animal health issues). This threat creates an incentive for the Chihuahua cattle industry to be well organized and to keep making efforts to produce higher quality cattle, and—most importantly—disease free cattle.

References

Carmona, Cristina and Rhonda Skaggs. Procedures for Exporting Cattle from Chihuahua, Mexico, to the United States. Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Report No. 43, New Mexico State University, January 2006.

Guinn, Christie and Rhonda Skaggs. Live Cattle Imports by Port-of-Entry from Mexico into the United States: Data and Models. Agricultural Experiment Station Research Report No. 788, New Mexico State University, August 2005.

Martínez Nevarez, Javier (Editor). Costos y Rentabilidad de la Producción de Carne Bajo Condiciones Extensivas y Costos de Producción y Rentabilidad de los Establos Lecheros en el Estado de Chihuahua. Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua Facultad de Zootecnia. Chihuahua, Chih., April 2002.

Mitchell, Diana, Rhonda Skaggs, William Gorman, Terry Crawford and Leland Southard. “Mexican Cattle Exports to the U.S.: Current Perspectives.” Agricultural Outlook June-July 2001:6-9.

Mitchell, Diana. Predicting Live Cattle Imports by Port of Entry from Mexico Into the United States. Department of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business, New Mexico State University. Unpublished master’s thesis, 2000.

Skaggs, Rhonda, René Acuña, L. Allen Torell, and Leland W. Southard. “Live Cattle Exports from Mexico into the United States: Where Do the Cattle Come From and Where Do They Go?” Choices, 1st Quarter 2004(a):25-30.

Skaggs, Rhonda, René Acuña, L. Allen Torell, and Leland W. Southard. “Exportaciones de Ganado en Pie de México Hacia los Estados Unidos: ¡De Donde Viene el Ganado y Hacia Donde Va?” Revista Mexicana de Agronegocios, Vol 14, January-June 2004(b ):212-220.

Appendix 1: Survey Instrument

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at aces.nmsu.edu.

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

Published and electronically distributed June 2007, Las Cruces, NM.