Guide H-655

Richard Heerema and John White

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Authors: Extension Pecan Specialist, Department of Extension Plant Sciences, and Doña Ana County Extension Agent, Cooperative Extension Service, New Mexico State University. (Print Friendly PDF)

It has been a relatively common practice in southern New Mexico to transplant mature pecan trees. Rather than wait for young trees to mature, some homeowners prefer to create "instant" shade and greenery by moving mature trees into their yards. Also, commercial pecan growers on occasion thin out trees from crowded orchards and start new orchards with the removed trees. Among commercial growers this practice has somewhat fallen out of favor since the late 1980s as mechanical pruning has become the standard practice in New Mexico; nevertheless, some commercial growers do continue to transplant mature trees today.

Transplanting mature trees today is often not economically feasible because high fuel and labor costs have made it significantly more expensive to transplant mature trees than to purchase and plant nursery trees. Furthermore, in only a few years yields of nursery trees become equal to those of transplant trees. But transplanted pecan trees do indeed provide shade and, if cared for properly, come into full nut production a few years sooner than new nursery trees planted at the same time. This publication describes how homeowners and commercial growers in New Mexico can maximize success in transplanting mature pecan trees.

The Transplant Process

A huge percentage of the root system is inevitably lost when large trees are transplanted, compromising the ability of a transplant tree to absorb water and nutrients. Consequently, all transplant trees, but particularly larger transplant trees, subsequently suffer from some degree of transplant shock, which can reduce vigor and nut production and, in extreme cases, cause tree death. For transplanting to be worthwhile, the transplant process must be carried out not only as quickly and efficiently as possible but also in a way that minimizes stress to the tree.

Pruning is a key factor in minimizing transplant shock. Before transplanting, commercial pecan growers usually severely prune their trees to minimize transplanting's disruption of the natural root–shoot balance. Some growers remove all limbs from the tree, leaving a post-like tree 7 to 10 feet tall; others retain three or four scaffold limbs, stubbing each of them back to 2 or 3 feet, in order to give the transplant a bit of a head start in developing its new canopy framework (Figure 1). Either way, such severe pruning creates much smaller canopies in the season after transplanting, reducing demand for water and making the transplants less prone to water stress and nutrient deficiency. In backyard situations where shade and aesthetics are considerations, it is preferable to prune less severely, but especially close attention must be paid to minimally pruned trees to ensure that they do not become critically water stressed.

Figure 1. Mature pecan tree with scaffold limbs in its first growing season after transplant.

Infection of large pruning wounds by wood-decaying microorganisms is not a serious concern in New Mexico, and it is not recommended that any sort of sealant be applied to pruning wounds. Severe pruning does, however, expose previously shaded parts of the tree's trunk to direct, intense sunlight, which can result in the trunk becoming sunburned, especially on the south and southwest sides. This damage can easily be prevented by painting the tree's trunk with a white latex (not oil-based) paint diluted 50% with water.

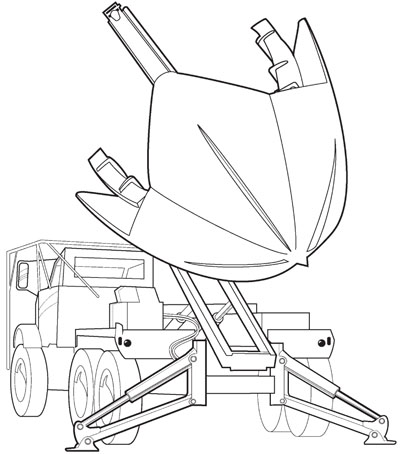

Mature trees to be transplanted are dug from the ground with a tree spade, a machine consisting of four (or occasionally six) hydraulically controlled shovels that form a cone shape when closed (Figure 2). There is a range in tree spade sizes; mature pecan trees are usually transplanted using a tree spade having the capacity to preserve a root ball of about 4 to 5 feet deep by 5 to 7 feet across the top. Tree spades are mounted to a tractor or, more commonly, to the back of a truck, allowing transport of the tree between the two orchard sites. Before digging each tree, a hole of the same dimensions as the root ball should be dug with the tree spade at the new planting site. The plugs of soil removed from the new site can be used to refill the holes left by tree removal.

Figure 2. Tree spade.

Mature pecan trees can be transplanted successfully at any time of year in New Mexico. However, winter-transplanted trees certainly experience far less water stress—orchard water loss is minimal when the weather is cool; the trees are dormant with minimal to no water needs; and the root system has a chance to regenerate before the heat of summer arrives. Consequently, winter-transplanted trees are generally expected to become fully established more quickly than summer-transplanted trees.

Transplant Care

Once the transplants are in place at the new site, the goals are, first, to maintain a 100% survival rate (this is possible even with relatively large trees!) and, second, to re-establish the trees' canopies and root systems as quickly as possible. To attain these goals, the following management factors must be considered:

Irrigation. Water stress is by far the most important factor limiting transplant establishment success. For the first few years, the root systems of transplanted trees are confined to a small soil volume near the trunk; so minimizing water stress for transplants not only requires special diligence in providing the right amount of water when the trees need it but also where the trees need it.

Around each newly transplanted tree, construct a soil berm that forms a circular basin extending a few feet past the edge of its root ball. As soon as possible, pump water into the basin to thoroughly wet the transplant's roots. Thereafter through the season, it remains critical to keep the transplants well irrigated; any unnecessary water stress will certainly be a major setback for transplant survival and establishment. Closely monitor the soil moisture near the transplants and irrigate so that the feeder roots do not dry out at any point (see Section A). It may be preferable, in the case of larger-scale plantings with flood irrigation systems, to remove the berms and begin use of the flood irrigation system in the first season following transplanting (see Section B).

For those with low volume (drip or microsprinkler) systems, and particularly on sandy soils, it is vital to pay close attention to irrigation water placement. Any part of a transplant's root system outside the area wetted by irrigation is likely to dry out and die. Since a low-volume irrigation system wets a smaller volume of soil than does flood irrigation, it is recommended that growers or homeowners not rely exclusively on low-volume irrigation systems and continue periodically flooding basins around transplants for at least the first three years, expanding the basins by a few feet each year to accommodate the growing root systems.

Fertilization. In the first 2–3 seasons following transplanting, pecan trees have low annual nutrient demands because they have limited root systems, along with severely pruned canopies and low nut production. Nevertheless, maintaining adequate leaf nutrient levels helps in large measure to ensure that the trees quickly recover from transplanting. In commercial orchards, leaf tissue analyses are the best indicator of the nutrient status of the transplanted trees and should be used to determine fertilizer application rates (see Section C).

Pecan transplants may become deficient in any one of the essential mineral nutrients but, more than any other nutrient, adequate (but not excessive) nitrogen (N) nutrition promotes vigorous root and shoot growth. Annually, N fertilizer should be applied to the soil near the tree so that it is easily within reach of the transplant's roots and is not lost to the environment. Depending on the soil type and native soil fertility in the orchard, about 20–30 lbs of actual N per acre (or about 0.4–0.6 lbs of actual N per tree) split into two applications should usually be sufficient in the first season after transplanting. Over the subsequent three seasons, as the trees become better established and nut yields rise, annual N fertilizer application rates should be progressively increased to the full amount recommended for established orchards. For more information about fertilizing orchards, consult the NMSU Extension publications listed in Section C.

Micronutrient deficiencies, especially zinc deficiency, are also a significant concern in New Mexico pecan trees because many micronutrients are unavailable to plants in New Mexico's calcareous soils. Micronutrient fertilizers are only effective when applied as foliar sprays. At least three foliar zinc applications are recommended each spring to promote transplant health and vigor. Some transplants may also require foliar iron, manganese, copper or nickel sprays each spring.

Pruning. The goal of pruning (training) during the first three to four years following transplanting is to reestablish the transplants' permanent branch structures, particularly if they were severely pruned before transplanting. The modified central leader is the most common tree form for pecan trees. To attain this tree form, each year a single vigorous central leader should be selected and pruned with a heading cut. Highly vigorous shoots competing with the central leader should be removed. Well-placed shoots that are less vigorous than the central leader should be selected to become the new scaffold limbs and should be tipped each year. Shoot thinning will likely also be required during the first few years, because new growth on transplants is often very dense and crowded. For more information about training and pruning pecan trees, consult the Extension publications listed in Section C.

Pest control. Until the transplants' root systems have had time to grow and fill a greater volume of the orchard soil, the most damaging pests will be weeds, which are strong competitors for both water and nutrients. To maximize water and nutrient uptake by transplant trees, it is essential in at least the first three years that an area extending at least 3 feet away from the transplants' trunks be kept entirely weed free throughout the entire year. The most effective way to maintain a weed-free area is through use of one or more of the numerous commercially available pre-emergence and post-emergence herbicides labeled for backyards or commercial pecan orchards.

Pesticide labels are legal documents. Be sure to read all pesticide labels and carefully follow all directions.

Two insect pest groups may also present a problem for transplant trees: aphids and wood-borers. Pecan aphids, specifically the yellow, black, and black-margined pecan aphid species, may infest pecan transplants and negatively affect establishment by reducing available carbohydrates from photosynthesis needed for growth. If aphids become a problem, there are numerous insecticides that are effective against pecan aphids available for backyards or commercial pecan orchards. Several species of wood-boring beetles occur in New Mexico. These insects rarely become a problem in unstressed pecan trees. However, they may occasionally bore into and damage exposed wood of stressed trees, including poorly maintained pecan transplants. Providing transplants with adequate water and nutrients can usually ward off wood-boring insects.

Finally, burrowing mammals such as gophers or ground squirrels may directly damage the already compromised root systems of transplant trees by eating new root growth. Tunnels dug by gophers and squirrels also can decrease irrigation efficiency by draining precious irrigation water away from the trees' limited root systems. Depending on the situation, these pests may be controlled by shooting, trapping or poisoning. For information about controlling burrowing mammals, consult the Extension publications listed in Section C.

For more information about transplanting pecan trees in New Mexico or about pecan production in general, please call your county Cooperative Extension office or visit New Mexico State University's pecan information website at http://pecans.nmsu.edu.

Section A

Trees transplanted to sandy sites may need to be watered as often as 1–2 times per week during the heat of the summer, but heavier soils (containing more clay), which have higher water holding capacities, may become waterlogged and anaerobic if they are watered too frequently. This, too, can be damaging to pecan trees' roots.

To learn more about soil moisture monitoring, see NMSU Extension publication

Guide H-640, Measuring Soil Moisture in Pecan Orchards

https://pubs.nmsu.edu_h/H640/

Section B

Only irrigation water applied within reach of trees' roots is available to the trees; the remainder is wasted. Since new transplants' root systems fill only a small proportion of the new orchard soil volume, there is no need at first to flood irrigate the entire area between the tree rows. In the first season following transplanting, commercial growers using flood irrigation may conserve irrigation water by constructing soil borders on both sides of each tree row, so that only the soil within 3 or 4 feet of each tree row is wetted during irrigation. If this practice is continued in subsequent seasons, each year the borders should be moved further away from the tree rows to accommodate the transplants' growing root systems.

Section C

NMSU Cooperative Extension Publications

For information about fertilizing orchards:

Guide H-602, Pecan Orchard Fertilization

For information about training and pruning pecan trees:

Guide H-605, Training Young Pecan Trees

For helpful tips for controlling burrowing mammals:

Guide L-109, Controlling Pocket Gophers in New Mexico

Circular 574, Controlling Rock Squirrel Damage in New Mexico

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu.

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

May 2008, Las Cruces, NM