Guide H-242

Natalie P. Goldberg and Jason M. French

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Authors: Respectively, Extension Plant Pathologist/Distinguished Achievement Professor; and Plant Diagnostic Clinician, Department of Extension Plant Sciences, New Mexico State University. (Print friendly PDF)

Diagnosis at a Glance|

Caused by |

Introduction

Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) is an important disease of many different crops grown in temperate and subtropical regions of the world. TSWV is a unique virus in a virus class by itself. The host range for TSWV is one of the widest known for plant viruses. It infects over 1,000 species in 85 families, including both monocots and dicots. In New Mexico, the virus has been confirmed in begonia, cowpea, impatiens, peanut, pepper, potato, squash, and tomato. Other common hosts include celery, cucumber, eggplant, lettuce, onion, peppermint, spinach, watermelon, many legumes, many ornamentals, and many weeds such as curly dock, field bindweed, and pigweed (Table 1). This disease is especially damaging in the ornamental and vegetable greenhouse industries.

In New Mexico, TSWV causes only sporadic problems in a small number of agronomic and ornamental plants. In other parts of the U.S., catastrophic losses—nearly 100% of some commercial fields—have been reported. Research on the virus population in New Mexico compared 285 viral isolates from multiple hosts to those from across the U.S. and around the world. Results of this study suggest NM is affected by a unique TSWV population only present in the southwestern U.S. This population likely arose due to geographic isolation and is related to other TSWV populations from the U.S., Spain, and Italy. Although the NM population of TSWV is distinct from other U.S. populations, it is still closely related to those that cause severe disease problems. Further research into vector populations and environmental conditions may provide clues to the factors that limit the disease pressure in NM.

|

Table 1. Partial Host Range of Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus1 |

|||

|

Ornamentals |

|||

|

African violet |

Columbine |

Geranium |

Poppy |

|

Amaryllis |

Cosmos |

Gladiolus |

Primrose |

|

Anemone |

Cyclamen |

Gloxinia |

Ranunculus |

|

Aster |

Dahlia |

Impatiens |

Salvia |

|

Begonia |

Delphinium |

Larkspur |

Snapdragon |

|

Calendula |

Dusty miller |

Marigold |

Statice |

|

Calla |

Exacum |

Nasturtium |

Stock |

|

Chrysanthemum |

Fuchsia |

Peony |

Verbena |

|

Cineraria |

Gaillardia |

Petunia |

Zinnia |

|

Vegetables |

|||

|

Bean |

Celery |

Kale |

Pepper |

|

Broccoli |

Cowpea |

Lettuce |

Potato |

|

Cabbage |

Cucumber |

Pea |

Spinach |

|

Cauliflower |

Eggplant |

Peanut |

Tomato |

|

Weeds |

|||

|

Burdock |

Curly dock |

Lambsquarter |

Pigweed |

|

Buttercup |

Field bindweed |

Morning glory |

Shepherdspurse |

|

Chickweed |

Jimsonweed |

Nightshade |

Wild tobacco |

|

Clover |

|||

|

Miscellaneous |

|||

|

Pineapple |

|||

|

1Table modified from Putnam and Dutky, Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus, Maryland Department of Agriculture. |

|||

Disease Symptoms

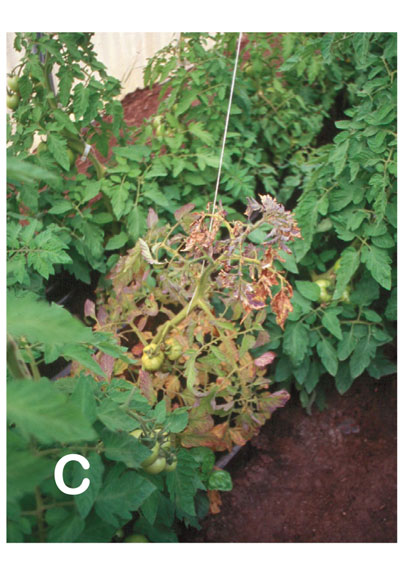

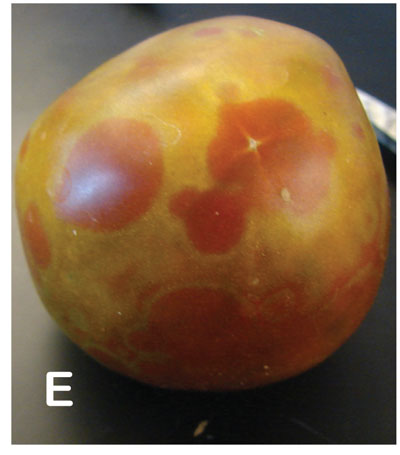

Symptoms of TSWV are numerous and varied. However, there are two fairly common symptoms for which this disease was named. First, the young leaves turn bronze and subsequently develop numerous small, dark spots. Second, the leaves often droop on the plant, creating a wilt-like appearance. Other symptoms include dieback of the growing tips, stunting, mottling, and dark streaking of the terminal stems. Affected plants may develop a one-sided growth habit or may be stunted completely. Plants that are affected early in the growing season often do not produce any fruit, while those infected after fruit set produce fruit with striking symptoms, including chlorotic concentric ring spots, raised bumps, uneven ripening, and deformation

(Figure 1). Infected plants produce poor-quality fruit and have reduced yield.

Figure 1(A). Symptoms of TSWV in New Mexico. Leaf tissue from a pepper plant exhibiting concentric ring spots, necrotic spotting, and leaf deformation.

Figure 1 (B). Symptoms of TSWV in New Mexico. Peanut leaf tissue exhibiting chlorotic flecking and ring spots.

Figure 1 (C) . Symptoms of TSWV in New Mexico. Infected tomato plant exhibiting wilting and bronzing.

Figure 1(D and E). Symptoms of TSWV in New Mexico. Fruit from pepper and tomato exhibiting uneven ripening in a ring spot pattern.

Figure 1 (F). Symptoms of TSWV in New Mexico. Cowpea leaves exhibiting necrotic flecking, veinal chlorosis, and leaf deformation.

Figure 1 (G) . Symptoms of TSWV in New Mexico. Mature pepper plant exhibiting terminal necrosis. Photo Credit: New Mexico State University.

Disease Transmission

TSWV is transmitted from infected plants to healthy plants by at least ten species of thrips. Thrips are tiny (approximately 1/16 of an inch) winged insects that feed on plants through sucking mouthparts. Thrips transmit the virus in a persistent propagative manner, which means that once the insect has picked up the virus, the virus replicates within the insect and the insect is able to transmit the virus for the remainder of its life. The virus is not passed on from adult to egg; however, progeny that develop on infected plants will quickly pick up the virus and be effective spreaders of the disease.

Disease Management

Controlling this disease is difficult. The wide host range, which includes many perennial ornamentals and weeds, enables the virus to successfully overseason from one crop to the next. Additionally, efforts to control the insect vectors in agricultural fields have had little effect on TSWV. This is likely due to the fact that large populations of thrips may fly or be blown into treated fields from non-treated areas nearby.

Controlling thrips is somewhat more effective in greenhouse situations. In greenhouses, however, growers should take care to avoid repeated sprays of similar insecticides because thrips are able to build up resistance to commonly used insecticides in a relatively short time. Rotating the insecticide class is the best approach to insect control. Control of thrips may be obtained with pyrethroids, carbamates, chlorinated hydrocarbons, organophosphates, and soaps. Insecticides are most effective when applied in the morning, when the thrips are most active and the chance for plant damage is reduced. Pesticide regulations change frequently, so check with your local county Extension office (http://aces.nmsu.edu/county/) for information on available insecticides.

While eliminating this disease may not be possible, the incidence and severity of TSWV may be reduced by using cultural practices such as starting with virus-free plant material, removing all infected plants (since there is no cure once a plant has the disease), controlling weeds, and rotating crops. Some studies have also shown that using reflective mulches under plants may help to reduce infection. In greenhouses, it may be possible to greatly reduce the number of thrips entering the greenhouse by covering doors and air intakes with a fine mesh (400 mesh) cloth. Efforts are underway to breed cultivars with good horticultural characteristics that also exhibit tolerance to the virus.

Selected References

French, J.M., N.P. Goldberg, J.J. Randall, and S.F. Hanson. 2015. New Mexico and the southwestern US are affected by a unique population of tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) strains. Archives of Virology. DOI: 10.1007/s00705-015-2707-5

Sether, D.M., and J.D. DeAngelis. 1992. Tomato spotted wilt virus host list and bibliography [Special Report 888]. Corvallis: Oregon State University Agricultural Experiment Station.

Sherwood, J.L., T.L. German, J.W. Moyer, and D.E. Ullman. 2009. Tomato spotted wilt. The Plant Health Instructor. DOI: 10.1094/PHI-I-2003-0613-02

For Further Reading

H-158: How to Collect and Send Plant Specimens for Disease Diagnosis

http://pubs.nmsu.edu//_h/H158/

H-248: Powdery Mildew on Chile Peppers

http://pubs.nmsu.edu//_h/H248/

H-250: Verticillium Wilt of Chile Peppers

http://pubs.nmsu.edu//_h/h-250/

Natalie P. Goldberg is a Professor and the Extension Plant Pathologist in the Department of Extension Plant Sciences at NMSU. She earned her B.S. in ornamental horticulture from Cal Poly Pomona and her M.S. and Ph.D. in plant pathology from the University of Arizona. Her Extension program focuses on plant health management, plant disease identification, and crop biosecurity.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu/

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

Revised May 2016