Guide H-248

Revised by Phillip Lujan

Extension Plant Pathologist, Department of Extension Plant Sciences, New Mexico State University. (Print Friendly PDF)

Powdery mildew is a common disease on chile peppers. The disease can be severe in arid and semi-arid growing regions, such as New Mexico. The fungus, which causes the disease, is Leveillula taurica. However, the fungus’ asexual stage, Oidiopsis sicula, is more commonly found in New Mexico. When the disease occurs early in the growing season, it can prematurely defoliate plants, resulting in significant quality and yield losses.

Biology of Powdery Mildew (Oidiopsis sicula)

The fungus can cause disease in a wide range of environmental conditions (40-95ºF, 0-100 % relative humidity). However, optimal conditions for infection and disease development occur when the temperature is between 60 and 80ºF with humidity greater than 85 %. Under favorable conditions, the fungus reproduces rapidly and spores can germinate and infect a plant in less than 48 hours. Wind-disseminated spores cause secondary infections, which help spread the disease. The fungus predominately infects the leaves, but it occasionally attacks the fruit and stems. The disease is most severe on older leaves just prior to fruit set, but it can occur at any time throughout the season if environmental conditions are favorable. Severe infections early in the season can result in heavy yield losses.

O. sicula has a wide host range, including cotton, onion, tomatoes and weeds, such as sowthistle and Wright’s groundcherry. However, not all susceptible hosts are infected in all areas. The inability of some fungal isolates to infect known hosts suggests that O. sicula actually may be more than one species or at least should be divided into formae speciales. At present, the fungus remains a single species. In New Mexico, the fungus can be a problem on chile peppers and is found on several weed species, but it has not been found infecting cotton or onion. The fungus survives between chile crops on other agronomic hosts and weeds. The amount of inoculum that survives each year depends on environmental conditions.

Signs and Symptoms

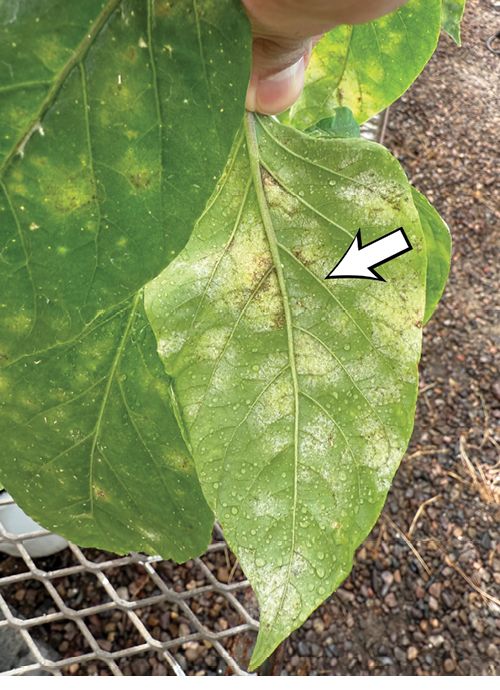

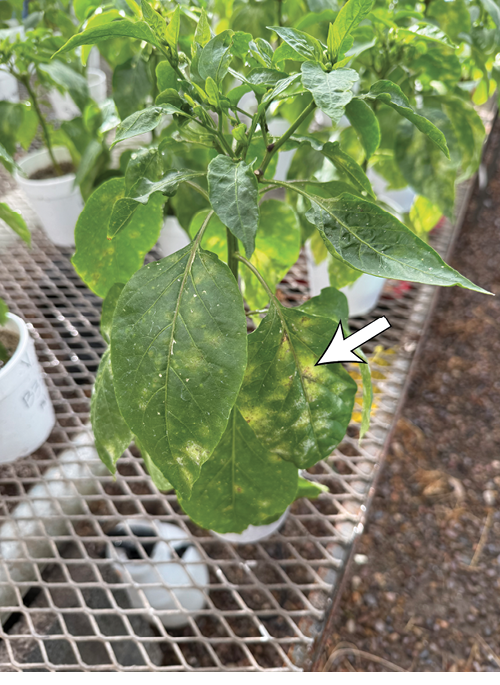

The disease’s primary symptom is the presence of a white, powdery, fungal growth that covers the lower leaf surface (Figure 1). The upper leaf surface may show a yellow or brownish discoloration and, in some cases, the fungus may actually sporulate on the upper leaf surface (Figure 2). The edges of infected leaves eventually roll upward exposing the fungus. Infected leaves will drop prematurely from the plant, exposing the fruit to the sun, which may result in sunscald.

Figure 1. White, powdery, fungal growth on lower leaf surface.

Figure 2. Upper leaf surface with yellow discoloration.

Management

Due to the fungus’ wide host range, sanitation practices (removing and destroying infected crop debris and weed control) in and around chile fields are not always sufficient to manage the disease. Additionally, most chile cultivars do not possess high levels of tolerance to this fungus. Because of these factors, management usually depends on using registered fungicides. The effectiveness of these sprays depends on early detection and thorough application coverage. Ground application with high-pressure and high-volume sprayers are recommended to ensure thorough penetration of the fungicide into the plant canopy. Fungicides with different types of chemistries should be rotated to prevent development of fungal strains resistant to the chemicals.

|

Table 1. Diagnosis and Management at a Glance |

|

|---|---|

|

Causal agent: |

Oidipsis sicula (Leveillula taurica). |

|

Hosts: |

Host range includes cotton, onion, tomatoes, eggplant, and weeds like sow thistle and groundcherry. |

|

Signs: |

White, powdery, fungal growth on leaves. |

|

Symptoms: |

Disease first shows on older leaves. Chlorosis. Necrotic, brown spots on upper leaf surface. Leaves curl upward. Premature defoliation. Sun scald as a result of leaf drop. |

|

Conditions for disease: |

Warm temperatures (from 40-95°F, optimum 60-80°F). High humidity (near 100%) for spore germination. Humidity between 35 and 95% for disease development. |

|

Management: |

Sanitation. Fungicide sprays. |

Original author: Natalie Goldberg, Extension Plant Pathologist.

Phillip Lujan is the NMSU Extension Plant Pathologist. He received his B.S. and M.S. in Agricultural Biology with a minor in Molecular Biology, and Ph.D. in Plant and Environmental Sciences with an emphasis in Plant Pathology at New Mexico State University. As the Extension Plant Pathologist, Dr. Phillip Lujan’s primary interest and responsibility is in the area of plant pathology and disease diagnostics for all New Mexico cropping and landscape systems. He also provides statewide extension programming with a focus on plant health and the use of integrated pest management strategies.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu.

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

Revised April 2025 Las Cruces, New Mexico