Circular 692

Robert Grassberger and Jay Lillywhite

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Respectively, Assistant Professor Emeritus, Organization, Information & Learning Sciences, University of New Mexico; and Professor/Department Head, Department of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business, New Mexico State University. (Print Friendly PDF)

Economic development stakeholders in New Mexico, including local governments, chambers of commerce, and state agencies, continuously investigate opportunities to strengthen the state’s economy and improve the lives of New Mexicans. One economic development strategy that has received attention recently is that of attracting retirees to the state. Previous research has suggested that, if properly designed, a successful retiree attraction program could positively impact the state fiscally (Grassberger and Lillywhite, 2018). Research outside of the state has suggested that retiree attraction programs can positively impact a state’s economy (Das and Rainey, 2007; Day and Barlett, 2000; Deller, 1995; Hodge, 1991; Hudson et al., 2015; Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism, 2010; Pages, 2008; Reeder, 1988; Stallmann et al., 1999). This research explores one retiree attraction program—Certified Retirement Communities—used by some states as a means of influencing preferences of potential retirees.

Courtesy photo by Michael Chastain.

What is a Certified Retirement Community?

A Certified Retirement Community (CRC) is an economic development tool used by states to advertise and promote select communities within the state. The primary goal of the CRC strategy is to entice retirees to move to the promoted community. The economic benefit is derived as retirees spend their retirement savings, pensions, and transfer payments (e.g., Medicare) within the region. Depending on the state, a “community” may be a municipality or it may be an entire county/parish. The CRC designation affirms that standards set by the state have been met and are being maintained as a condition of continued certification. Hence, a CRC designation signals to a retiree (or anyone considering relocation) that the standards reported by a community have been audited by the state and certified as truthful and factual. CRCs can also serve as a tourism development tool in that they can be used to promote exploration of other regions of the state not historically perceived as tourism destinations, thus creating impact from new tourist dollars.

Specific guidelines and standards for CRC designation vary, but several generalities can be observed in most CRC programs. Individual communities are required to make an application for certification through a state agency or a state-designated third party. The certifying agency establishes and ensures communities meet standards to qualify for the CRC designation. Once the application has been filed, it is reviewed and, if approved, these communities can begin to use the certification status in their advertising campaigns. Generally, there is an associated application fee, an annual participation fee, and a commitment to stay in the program for a designated number of years. Additionally, communities are subject to recertification after a predetermined time (e.g., five years).

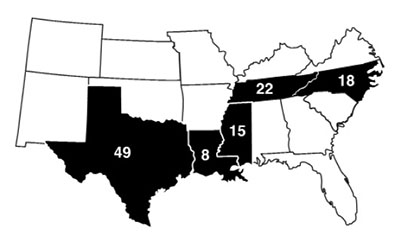

Figure 1. Number of active Certified Retirement Communities by state.

|

Table 1. Certified Retirement Community |

||

|

State |

CRC geography |

Number of CRCs |

|

Louisiana |

City/Parish |

8 |

|

Mississippi |

City |

15 |

|

North Carolina |

City |

18 |

|

Tennessee |

County |

22 |

|

Texas |

City/County |

49 |

Where are Certified Retirement Communities Being Used?

Mississippi was the first to use a formal CRC program to attract retirees. According to Ramay Winchester, director of Retire Tennessee, many of the CRC programs in operation today were modeled after the Mississippi program (Winchester, personal communication, 2018). Today there are five states using CRC programs2, with over 100 certified communities. The programs are located primarily in the Southeast3, and almost half of these certified communities are in Texas (Figure 1). Table 1 shows that states certify retirement communities at different geographic levels; some use cities, others use counties or parishes, and some use both. Tennessee, for example, certifies at the county level so that municipalities within the same county would not be in competition with each other. Arkansas (not shown) does not promote individual communities, but instead promotes opportunities in the state by region4.

In addition to state-level certification or in states that don’t have a CRC program, communities can obtain a Seal of Approval through the American Association of Retirement Communities (AARC). AARC is a not-for-profit professional association established in 1994 that supports states and municipalities, as well as community developers and for-profit businesses, who market to retirees (AARC, 2018a). The Seal of Approval “recognizes communities who have made a commitment—both in ‘hard’ amenity offerings and ‘soft’ programs—to a ‘best in class’ lifestyle for retirees” (AARC, 2018b). Currently, 23 communities from six states have received the association’s Seal of Approval. Nine developers from seven states have the Developer Seal of Approval.

What are the Benefits of Certified Retirement Communities?

Economic development specialists indicate that there are two primary benefactors of attracting retirees with CRCs: the relocating retiree and the state/community hosting the program.

Benefits to relocating retirees

From a retiree or potential retiree perspective, CRCs can serve as a “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval,” reducing some of the risks associated with relocation (Winchester, personal communication, 2018). Retirees contemplating a CRC benefit from having access to data that has been collected and vetted by a third party, e.g., a state agency. Some of this data may be unique to the CRC program and unavailable from other sources. Retirees or potential retirees considering relocation can then make an apples-to-apples comparison of the certified communities in the state. Increased information via the CRC data can facilitate better decisions for the potential relocating retiree.

Benefits to state/community

From a state or community perspective, CRC programs provide a marketing tool for participating communities and states. While the programs are designed to inform and attract potential retirees, they also encourage tourism for communities that might be otherwise overlooked since potential retirees or retirees considering relocating often will first visit to explore the community. Pat Mason, co-founder of Carolina Living, says that states benefit directly economically and fiscally from the spending of “tourists” exploring a community and from the spending of retirees who bring “mail box income5” in the form of retirement pensions, investment income, and Social Security (Mason, personal communication, 2018). Communities that are successful in their certification bid can improve their marketing and promotional effectiveness since their acceptance to the CRC program makes them part of an elite “club.” CRC program membership can be used by the community to differentiate itself in its advertising and promotional campaigns.

State CRC programs may provide the following as benefits to CRC communities:

- Promotion of the certified community in program outreach campaigns to retirees and potential retirees both in and outside the state6. Promotional tools that may be extended to CRCs could include such things as a landing page maintained by the CRC program with links to CRCs, distribution of certified community brochures at state events and trade shows, and directory service for inquiries to or about CRCs.

- Marketing assistance (including web page design) used in promoting the community as a desirable retirement location. This may also include working with and supporting each CRC in identifying and evaluating the unique community qualities that make it a preferred retirement destination.

- Technical assistance in developing a community where retirees would find attractive retirement lifestyles and in enriching their locations, resulting in positive economic development.

- Maintenance of a certification program that is a reliable and trusted source of information.

- Promotion to encourage tourism traffic to the community.

- Assist and facilitate CRC representatives’ attendance at retiree planning conferences like the Ideal-Living Resort and Retirement Shows (Ideal-Living, 2019).

Benefits of CRC programs: Case examples

Judy Avery, a marketing consultant, reported in a presentation at the 2017 AARC Conference that, in the first year of participating as a CRC, her community of New Bern, North Carolina, was able to attract 44 new households that added an estimated $9 million in new direct spending to the community (Avery, 2017).

Jeff Fleming, the city manager for Kingsport, Tennessee, estimates that every newcomer who arrives in his community adds an additional $25,000 in direct spending (Fleming, 2014; personal communication, 2018a). Kingsport, a town with a population of just over 53,000 and without a Master Planned Community, uses the CRC designation broadly as a marketing tool not just to attract retirees but also as a magnet for attracting families. According to Fleming, the amenities retirees desire in a community are much the same as those that millennials with families want (Fleming, 2018b). Over a seven-year period, Fleming tracked a net of 772 new households (approximately 110 households per year) moving into his community from other states. While the causality can’t be entirely attributed to the existence of the CRC designation, Fleming estimates the benefit to his community of these in-migrating households to be in excess of $44 million in new spending annually (Fleming, 2014). In addition to the increase in population, Fleming also reports a corresponding increase in educational attainment and median incomes, and an increased depth of the regional talent pool.

Who has Oversight for the Certified Retirement Community Program?

Table 2 shows existing CRC programs and the agency that has oversight of the program. North Carolina’s CRC program, started in 2008, uses a partnership model for oversight (Hudson et al., 2015). Visit NC, a public-private organization, manages the program in cooperation with the Department of Commerce7 (Visit NC, 2018). The Texas CRC program, almost a decade old, is located in the Department of Agriculture as part of their larger rural economic development strategy (GO TEXAN, 2018). Initiated almost 30 years ago by the mayor of Madison, the Mississippi CRC program has been going on longer than any other in the U.S. (Vassallo, personal communication, 2018). The program is administered by the Mississippi Development Authority, Mississippi’s lead economic and community development agency (MDA, 2019). Tennessee’s CRC program, in its 14th year, and Louisiana’s program, recently being rekindled after difficulties with Hurricane Katrina, are both administrated through their respective state tourism agencies.

|

Table 2. State CRC Programs and Oversight Agency |

||

|

State |

Program name |

Oversight agency1 |

|

Louisiana |

Louisiana Encore |

Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism |

|

Mississippi |

Hometown Mississippi |

Mississippi Development Authority |

|

North Carolina |

Retire NC |

Visit NC and North Carolina Department of Commerce |

|

Tennessee |

Retire Tennessee |

Tennessee Department of Tourist Development |

|

Texas |

GO TEXAN |

Texas Department of Agriculture |

|

1The state and/or private agency that oversees the certification process. |

||

What Does it Take to Become a Certified Retirement Community?

As indicated earlier, much of the CRC process was seeded in Mississippi, and other state programs have been built from that foundation (Winchester, personal communication, 2018). Thus, the qualification standards and the application process look much the same from state to state8. Links to the standards, guidelines, and applications from several states have been included in the Resource Links section of this report. Links to examples of the legislative language used to establish CRC programs are also provided in the Resource Links section.

While the oversight agencies offer such services as support and training, the CRC application process requires substantial effort on the part of interested communities. Applicants must first be recognized as local government entities (municipalities or counties)9. The effort must be led by a local champion, and the community must form a support committee comprised of members committed to the long-term success of the initiative. Further, the committee is required to gather letters of support from local business, churches, and non-profit agencies from the area.

The local committee is tasked to pull together a variety of community data. Criteria for the community selection process include items such as climate, demographics, tax structure at the state and local levels, local housing availability, public safety and crime index, employment and volunteer opportunities, healthcare and medical services, public transportation, recreational areas, and festivals and fairs10. The process also requires a marketing plan, a discussion of any local budgetary support, and often commitments by the local community to send people to both training and promotional events, including trade shows. The level of detail required by Texas can be seen in the application for Paducah, Texas11, that is linked from the Resource Links section of this document.

The completed plan is then reviewed by an oversight board. Membership of the board is often through appointment by the governor or a state official. Applications are typically accepted only once or twice annually and are reviewed within 90 to 120 days. Applications that are rejected can be resubmitted at later dates.

Once an application has been approved, the community can then begin to use the state’s certification stamp in their advertising. However, as part of the agreement most certifying agencies require that the demographic and statistical data be updated each year.

Fees and Costs to CRCS

As part of the application process, communities agree to fees for becoming certified. In some states, this is a lump sum payment good for five years. Other states have moved to an annual payment, but require the community to commit to a five-year term with the CRC program. In addition to the fees paid to state agencies, communities may also incur costs for developing their own advertising and promotional campaigns. Many communities also send representatives to events that introduce potential retirees to their community. Still others send representatives to educational conferences on marketing their communities to retirees. Accordingly, annual costs could be several thousand dollars more than just the application fee.

Examples of CRC fees and costs

Texas assesses a $5,000 fee at the time of the application that recurs at recertification in five years. Alternatively, Texas communities can pay a fee of $0.50 per capita based on the current population. At the inception of the program, communities participating in North Carolina were charged a lump sum fee of $10,000 for a five-year certification. Since many small community budgets were stressed by the upfront fee, this policy was recently changed, and North Carolina CRCs now pay $3,000 annually with a commitment to participate in the program for five years according to Andre Nabors of Retire NC (Nabors, personal communication, 2018). In Tennessee, CRCs pay $3,000 per year and are encouraged to join the state agency representatives at the Ideal-Living shows at their own expense (Winchester, personal communication, 2018). According to Steve Vassallo, a rural development expert who presented at the 2018 AARC Conference, many of these communities use funds from lodger’s taxes or have added local options to sales taxes to cover these fees (Vassallo, personal communication, 2018).

Tracking the Impact of the CRC Strategy

Unlike recruiting businesses to a state where the evidence of an attraction campaign is relatively easy to track, evaluating the success of retiree attraction campaigns is much more difficult. Retirees considering a community may not be visible to the community or to the CRC program administrator. While some metrics are easy to track, e.g., click through rates and other web metrics for those who go to web pages, it is far more difficult to track the impact of a CRC program. That is, was the program successful in recruiting retirees to a particular community in the state? Not only is it difficult to know the identities of who is looking at online materials, the decision process itself has a “long fuse”—there is often a lag time of many years before retirement and relocation.

According to the director of the Retire Tennessee program, one of the challenges with tracking is that “the product doesn’t show” (Winchester, personal communication, 2018). In other words, it is seldom known if the effort has been successful since there is little way to know who shows up and why they came unless they contacted someone connected to the CRC program. Nevertheless, several different approaches at collecting data are being attempted. Most communities with CRCs have a chamber of commerce or city executives who work closely with realtors who ask home buyers at closing for the zip codes of the area they are moving from. This allows a raw count of new households but may not be specific to retirees unless they are moving into age-restricted communities. Similarly, some communities collect zip code data through their water utility companies for new hookups. Again, this offers a gross count of households but not necessarily those tied to the CRC program or, for that matter, to retirees in general.

Because many of the states and local communities attend trade shows that cater to retirees exploring retirement relocation options, more detailed data can be acquired from face-to-face contacts at the shows. Contact data is collected at the state or community booths that may include name, email address, mailing address, and phone number. Known as “top of the funnel” lists, these data represent potential retirees with an interest in relocating who can be contacted with additional information and tracked to see if they eventually move to the community. Indeed, there are companies who, if provided with this list, can use other sources of public data to develop a rich profile of these prospective movers (Peters, 2018). Relocations can be tracked through the National Change of Address database. North Carolina is currently using this approach quite successfully (Nabors, personal communication, 2018).

There are other ways to collect “top of the funnel” data beyond trade shows. For example, events that draw large numbers of tourists can provide direct contact for potential out-of-state retirees or potential retirees. Virtually all states and many individual CRCs also offer incentives through their websites, such as relocation packets, that require interested parties to provide email addresses as a condition of receiving the materials. Thus, collecting an email address provides not only a way to market to people who have shown an interest but also offers a seed for tracking the effectiveness of the retiree attraction program.

Potential Risks and Barriers to Implementing a CRC Strategy

As with any strategic effort, a program must also consider the potential downsides and barriers encountered in the implementation and administration process. The success of a CRC program requires effective administration and significant attention to purposeful marketing and advertising. Merely having a CRC designation will not result in retirees flocking to these New Mexico communities. It is but one piece of a comprehensive marketing strategy for getting people to move to the state. Some of the other possible risks are listed and addressed briefly below.

Resource allocation

Communities and local governments must carefully consider how they allocate their scarce resources, including monetary and human resources. As discussed earlier, the existing state CRC programs charge fees to communities for the CRC designation. These fees represent a monetary outflow from the community. Additionally, most CRC programs have expectations that representatives from these communities will attend trainings and promotional events, adding costs to program participation. Further, the state-level oversight agency will incur the costs of developing and delivering training, attending promotional events, and program administration.

The application process itself will be time-consuming for communities on the development side and for oversight agency representatives tasked with reviewing and scoring applications. Once CRC approval has been achieved there are, as part of the continued certification process, annual administrative requirements for updating the local data to include tracking and reporting the impact of the program to the community. Compliance with certification standards is a cost to both the community and the oversight agency.

The specifics of a New Mexico CRC program roll-out would need to be determined. While there are many examples of how states have built these programs, starting a New Mexico CRC program will require time and money. This discussion also requires a determination of who at the state level is willing to take on program oversight.

At the community level, the time and costs of application preparation and the need for program compliance are likely to constrain the number of applicants in New Mexico. Indeed, one of the key factors in the selection process will likely be the willingness of communities to devote the resources to even apply to the program.

Political support

When compared with other, more traditional approaches to economic development and/or tourism, initiatives aimed at attracting retirees may not get the attention of legislators and agency directors. Unlike business recruitment and tourism attraction, much of the impact from retiree attraction is mostly invisible12 because it is primarily through household consumption. Thus, support for retiree attraction programs and the associated funding may not find its way to the top of legislative agendas.

Politics could potentially enter into decisions about which communities should or should not be included as CRC designates. While states using a CRC strategy have gone to great lengths to establish rubrics13 that weigh different community attributes, the very nature of grading makes it subjective. For example, determining if a community has a thriving retail center is a matter of perspective. Consequently, communities who are not selected may feel they were scored unfairly. The process is also subject to attempts at political influence as area representatives seek consideration for their respective communities.

No guarantee of a return

Ultimately, as with any change initiative, there is no guarantee of success. In the case of retirees who relocate, it may be difficult to even know if they have arrived in a community, much less know what sparked them to choose that area. Further, for most retirees considering relocation, the time between considering an area and making the choice to move is a relatively long process. Hence, the strategy may take years to manifest results, and those results may be difficult to track. While CRCs appear to have worked elsewhere, they may not work in New Mexico.

Conclusion

Five U.S. states currently use Certified Retirement Communities as one mechanism for attracting retirees to specific cities or counties rich in the lifestyle amenities retirees seek. CRC programs are developed and managed by state agencies or their designees. Because the goals of the CRC are to create impact through retiree consumption-based spending, CRC programs are often housed in tourism rather than in economic development. CRCs may also be postured as a rural development strategy.

The CRC designation acts as a brand that allows those wanting more information about possible retirement communities to quickly learn about aspects of those locations important to retirees. The designation acts as a “state seal of approval” that promises the potential relocating retiree that the state has certified that the community has the amenities as stated.

There are obligations and costs for the communities that participate in these programs. Having a CRC designation does not guarantee a community success in attracting retirees. Indeed, tracking the success of CRC programs can be a challenge because it is difficult to determine who recently moved into a community and what motivated them to select this area. The communities that have been most successful as CRCs have found unique ways to track new in-migrant retirees. These communities also take an active role in outreach beyond what the state provides.

The CRC designation is generally only one component of a larger strategy to attract retirees to a state. A larger strategy often involves marketing to potential retiree relocators through print advertising, social media, and other methods of outreach to this target audience.

Resource Links

List of Certified Retirement Communities

Louisiana: https://www.louisianatravel.com/retire

Mississippi: https://www.mississippi.org/retirehere/

North Carolina: https://www.retirenc.com/certified-communities

Tennessee: https://www.tnvacation.com/retire-tennessee/communities

Texas: http://www.retireintexas.org/Home/Resources/CertifiedCommunityLinks.aspx

State web pages for retiree attraction

Alabama Advantage: https://www.alabamaadvantage.com/

Retire to Arkansas: https://www.relocatearkansas.com/retirement/

Visit Mississippi: https://visitmississippi.org/travel/retirement/

Retire North Carolina: https://www.retirenc.com/

https://www.retirenc.com/files/files/retirenc-inserts.pdf

Retire Tennessee: https://www.tnvacation.com/retire-tennessee

Retire in Texas: https://www.retireintexas.org/

Examples of Certified Retirement Community applications and standards

American Association of Retirement Communities (AARC) Seal of Approval:https://the-aarc.org/seal-of-approval/

Louisiana

Encore Louisiana Commission Certified Retirement Community Program Guidelines & Application: https://www.crt.state.la.us/Assets/Tourism/retire/Encore-Louisiana_Commission-Criteria-Application.pdf

Encore Louisiana Committee Membership:https://www.crt.state.la.us/tourism/retire/index

Texas

GO TEXAN Certified Retirement Community Program Guidelines: https://www.retireintexas.org/Portals/10/Documents/CRC%20-%20Guidelines_2014.pdf

Texas CRC application form: https://www.retireintexas.org/Portals/10/Documents/CRC%20Application-2015.pdf

Paducah, TX, completed application: https://www.paducahtx.com/Paducah-application.pdf

North Carolina

NC Certified Retirement Community Program: https://partners.visitnc.com/retire-1

Examples of statutes and laws

Louisiana

https://legis.la.gov/Legis/law.aspx?d=104000

https://legis.la.gov/Legis/law.aspx?d=104001

North Carolina

https://www.ncleg.gov/enactedlegislation/statutes/pdf/bysection/chapter_143b/gs_143b-437.100.pdf

https://www.ncleg.gov/enactedlegislation/statutes/pdf/bysection/chapter_143b/gs_143b-437.101.pdf

Texas

https://texas.public.law/statutes/tex._agric._code_section_12.040

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank those who reviewed this research. Reviewers included Dr. Michael Patrick, Associate Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business, New Mexico State University; Jerry Schalow, President and CEO, Rio Rancho Regional Chamber of Commerce; and Patrick Vanderpool, Executive Director, Greater Tucumcari Economic Development Corporation.

Footnotes

2 In the early 2000s, West Virginia and Washington had CRC programs, but these have been abandoned as political support has waned (Winchester, personal communication, 2018). (back to top)

3 For additional detail about these communities, see the Resource Links section at the end of this publication. (back to top)

4 Arkansas has a robust retiree attraction program headed by the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism. At the state level, it promotes six regions of the state. There is also a substantial developer presence in Arkansas. Hot Springs Village is the largest gated community in the U.S., with a population of over 40,000 retirees (Hot Springs Village, 2018). (back to top)

5 The term “mail box income” signifies that retirees with pensions and transfer payments are not dependent on employers for their monthly income. Each payday they have only to walk out to the mail box to collect their check(s). (back to top)

6 As an economic development program, some states want to solicit only to those who come from other states. This is roughly equivalent to the promotion of economic base jobs. For example, Tennessee promotes only outside the state while Texas markets to both out-of-state and in-state retirees. (back to top)

7 North Carolina’s program is tightly coupled to tourism because they have found that almost two-thirds of those who relocate to the state first visited as tourists (Mason, personal communication, 2018; Nabors, personal communication, 2018). (back to top)

8 For a brief overview of each state CRC program and its requirements, see the discussion in Attracting Retirees to South Carolina (Hudson et al., 2015). (back to top)

9 In other words, an interested group of citizens can’t apply for a CRC designation without having a commitment from a city or county government. (back to top)

10 The application forms for Texas and Louisiana include rubrics with the items and the weighting schemes used for scoring in these states. The links to these forms are included in the Resource Links section of this report. (back to top)

11 The Paducah, Texas, application is presented as an illustration. Applications from other entities may be less comprehensive and still good enough to meet the certification requirements. The important part of the application process is meeting the requirements in the individual state scoring rubric. (back to top)

12As much as 21% of Colorado’s economic base may be attributable to retiree spending according to a recent article (Binnings, 2018). (back to top)

13For an example of detailed rubrics, see the links to the Texas and Louisiana applications in the Resource Links section of this publication. (back to top)

For Further Reading

CR-643: Tools for Understanding Economic Change in Communities: Economic Base Analysis and Shift-Share Analysis

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_circulars/CR643/

CR-652: Closing Retail Sales Gaps: Boosting the Economic Fortunes of Rural New Mexico Counties

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_circulars/CR652/

CR-691: Potential Fiscal Impacts of a New Mexico Retiree Attraction Campaign

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_circulars/CR691/

Reference

American Association of Retirement Communities. 2018a. Homepage [Online]. https://the-aarc.org/

American Association of Retirement Communities. 2018b. Seal of approval [Online]. https://www.retirementdestinations.org/

Avery, J. 2017. Improving the ROI on your retire program [Presentation; online]. https://vimeo.com/user43273265/review/244919235/6b86f07c4e

Binnings, T. 2018, November 7. The Colorado economy: Different ways to look at the same thing [Online]. ColoradoBiz. https://www.cobizmag.com/Trends/The-Colorado-Economy-Different-Ways-to-Look-at-the-Same-Thing/

Das, B., and D. Rainey. 2007. Is attracting retirees a sustainable rural economic development policy? Paper presented at the Southern Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meetings.

Day, F.A., and J.M. Barlett. 2000. Economic impact of retirement migration on the Texas Hill Country. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 19, 78–94.

Deller, S.C. 1995. Economic impact of retirement migration. Economic Development Quarterly, 9, 25–38.

Fleming, J. 2014. If you can’t measure it, it doesn’t count [Presentation; online]. https://vimeo.com/109732990#t=0s

Fleming, J. 2018a, November 8. Personal communication; interviewer: R. Grassberger.

Fleming, J. 2018b. Is your community stepping up to become age-friendly and livable? [Presentation; online]. https://vimeo.com/user43273265/review/301280033/e3b41566d9

GO TEXAN. 2018. Certified Retirement Communities [Online]. http://www.retireintexas.org/Home.aspx

Grassberger, R., and J. Lillywhite. 2018. Potential fiscal impact of a New Mexico retiree attraction campaign [Circular 691; online]. Las Cruces: New Mexico State University Cooperative Extension Service. https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_circulars/CR691.pdf

Hodge, G. 1991. The economic impact of retirees on smaller communities: Concepts and findings from three Canadian studies. Research on Aging, 13, 39–54.

Hot Springs Village. 2018. Welcome to Hot Springs Village Arkansas [Online]. http://hsvpoa.org/

Hudson, S., F. Meng, K. Kam Fung So, and D. Cardenas. 2015. Attracting retirees to South Carolina [Online]. Columbia: University of South Carolina. https://sc.edu/study/colleges_schools/hrsm/research/centers/richardson_family_smartstate/pdfs/studies/smartstate_retiree_annual_report_11_10_16.pdf

Ideal-Living. 2018. Executive report 2018: The marketplace for buyers of retirement or second homes [Online]. https://www.rpimedia.com/welcome/publications/2017-executive-summary/

Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism. 2010. Louisiana Retirement Development Commission [Online]. https://www.crt.state.la.us/Assets/documentarchive/impact-report/Retirement.pdf

Mason, P. 2018, October 15. Personal communication; interviewer: R. Grassberger.

Mississippi Development Authority. 2019. Retire Mississippi [Online]. https://www.mississippi.org/retirehere/

Nabors, A. 2018, November 8. Personal communication; interviewer: R. Grassberger.

Pages, E.R. 2008. What do we know about retiree attraction strategies? Economic Development meets the coming age wave. Applied Research in Economic Development, 5, 48–54.

Peters, K. 2018. Moving your leads through the funnel [Presentation; online]. https://vimeo.com/user43273265/review/301294024/8c9a6ef392

Reeder, R.J. 1988. Retiree-attraction policies for rural development [Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 741; online]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/42147/43214_aib741b.pdf?v=0

Stallmann, J.I., S.C. Deller, and M. Shields. 1999. The economic and fiscal impact of aging retirees on a small rural region. The Gerontologist, 39, 599–610.

Vassallo, S. 2018, November 8. Personal communication; interviewer: R. Grassberger.

Visit NC. 2018. Certified Retirement Communities [Online]. https://www.retirenc.com/certified-communities

Winchester, R. 2018, October 4. Personal communication; interviewer: R. Grassberger.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced, with an appropriate citation, for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

June 2019 Las Cruces, NM