An Industry-University Response to Global Competition1

New Mexico Chile Task Force Report 1

Joel A. Diemer, Richard Phillips, and Mark Hillon

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Authors: Respectively, Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business iirm@nmsu.edu; Project Manager, Chile Task Force, Cooperative Extension Service, rphillip@nmsu.edu; and Graduate Assistant, New Mexico State University College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, Las Cruces, mhillon@nmsu.edu, all with New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Introduction

The scheduled reduction in trade barriers set in motion by the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) have forced many U.S. agricultural producers to take a lesson in geography. For decades, many could scope out their competition simply by driving a few miles down the road. Today, they are pulling out maps and searching for locations in Asia, Africa and South America. Low agricultural input costs give growers in these regions an edge in new global rivalries. In the late 1990s, New Mexico chile producers took a hard look at their new competition and at the new rules of trade. They realized that they were looking at a whole new game. If they continued to play the same old way, they were destined to lose. In 1998, industry representatives approached New Mexico State University’s College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences for help in devising a new game plan. The result was the formation of the New Mexico Chile Task Force. Its inception and achievements in three years’ time hold lessons for U.S. producers of other commodities. Most important are learning to set aside traditional differences and developing strategies to use the most up-to-date knowledge and technology to maximize profitability.

For New Mexicans, the chile pod is a cultural icon. The state has chile festivals, a Chile Commission, a Chile Institute, a university rugby team called the Chiles, mail-order businesses that specialize in shipping chile worldwide, a monthly publication about chile, and countless restaurants that specialize in some variation on the theme. To many, the thought that New Mexico might not have a commercially viable chile industry seems preposterous. It is a concept roughly comparable to France without a wine industry. Yet, in the late 1990s, the demise of chile in New Mexico seemed imminent. Cheaper imports from neighboring Mexico--and distant Zimbabwe, India and South Africa--were pouring into the state, while New Mexico chile pepper acreage declined by 54 percent. Processors were poised to relocate closer to their sources, threatening a loss of jobs and erosion of rural tax bases.

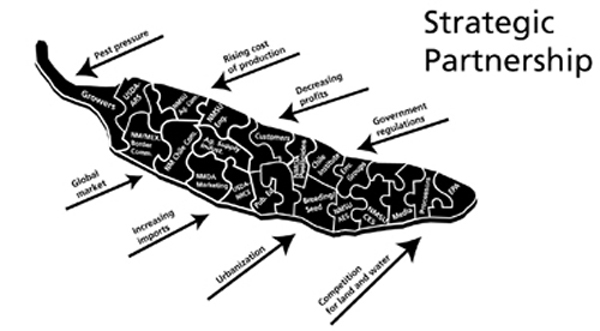

Figure 1. The New Mexico Chile Task Force draws members from industry, the university and federal, state, and local agencies.

It is ironic that just when salsa was overtaking ketchup as America's favorite condiment, farmers who produce the key salsa ingredient were facing a crisis. Perhaps the now-retired salsa ad catchphrase “Made in New York City?” was an early warning sign that something was amiss. In the ad, the cowboys’ implied “solution” to the problem was hanging the messenger and returning to business as usual. While getting on with business historically has been one of the great strengths of American farmers, there are times when it is a liability. One of those times is when just getting on with business (particularly if it means continuing to discount the rest of the world) is tantamount to committing economic suicide.

The Concept Behind the Task Force

In 1998, when members of the New Mexico chile industry sought help from the college to keep the industry alive, college representatives concurred that the loss of chile pepper production and processing in New Mexico would represent a major economic and cultural loss for the state. In November 1998, the New Mexico Chile Task Force was formed “to identify and implement ways to keep chile pepper production profitable in New Mexico and to maintain and enhance the R&D partnership between the New Mexico chile industry and New Mexico State University” (Diemer, 1998). Organizers envisioned that representatives from each sector of the chile industry would be involved actively with NMSU Cooperative Extension Service specialists and researchers who could bring new knowledge and technology to bear on the problems facing the industry. In addition, the Task Force would include members of other federal, state and private groups with ties to the chile industry. The organizers’ first task, however, was solidifying the Task Force team.

Participant Selection for the Task Force

To successfully promote change in the industry, Task Force organizers recognized the need for every part of the chile industry to become involved. They used a two-step referencing process to identify a diverse group of individuals who could contribute important, yet different, pieces of information about the state of the industry (fig. 1). In the first step, organizers “mapped” the chile industry, identifying major processing companies, growers, New Mexico Department of Agriculture (NMDA) representatives, agriculture supply sector representatives, and NMSU researchers and Extension specialists with an interest in the industry. An initial reference group of core industry participants was identified, representing each section of the industry map. Initial participants were selected for their intimate knowledge of their particular part of the New Mexico chile industry and for their willingness to work collaboratively to improve the industry. This initial step located opinion leaders who could catalyze a groundswell of interest from the industry at large.

The second step in the referencing process was “community referencing,” used to identify the specific individuals who would actively participate as Task Force members. Individuals identified in the first step were asked to nominate additional industry participants who met the nomination criteria. Whenever possible, those new nominees were asked to make nominations. This process of internal nomination and cross-referencing gave credence to the participant selection process and ensured that the most knowledgeable people possible were involved in addressing the industry’s future. Eventually, 50 people were invited and more than 95 percent participated.

Strategic Planning Methodology

The New Mexico chile industry was characterized historically by intraindustry disagreements that could be as heated as the spicy industry product. With this unpromising history in mind, the organizers selected a strategic planning methodology called Search Conference Method for Participative Planning. Experience has shown that Search Conferences that include people with the widest range of firmly held beliefs often produce the most constructive results (Blick, 2001). One of this method’s most powerful applications is that it can enable enterprises that seek to create partnerships to discover areas of agreement or disagreement and to come to terms with the areas of disagreement, thus making their relationships sustainable (Cabana, 2001). Based on the work of Fred Emery and Eric Trist in the 1960s, the Search Conference is a participative method that enables people to create a plan for their organization’s most desirable future. (Blick, 2001). It helps them to identify specific actions that can be taken and solidifies support for the people who will be responsible for making the necessary changes. During the past 35-plus years, hundreds of organizations credit their organizations’ long-term success to use of the Search Conference Method.

The Search Conference process applies open-systems theory to the real world. Open systems theory proposes that all systems are open to their external environment and are constantly affected by changes in that environment. During the Search Conference process, members learn how they can influence their environment by developing strategies that stabilize some of its parameters (Cabana, 2001). While the environment remains uncertain, participants understand it and have a plan to make it more manageable.

The Search Conference Process

The Search Conference is a highly participative, yet structured and task-oriented process. It is summarized by Diemer and Alvarez (1995) as follows:

Pre-Conference Activities

- Initiation: A need is felt and expressed by system members.

- Task selection: The objectives of the Search Conference are identified and clarified.

- Planning and preparation: Participants are selected and a workshop is designed.

Conference Activities

- World scan: Participants gather information to determine the most probable and desirable futures of the world outside of their system.

- System scan: Participants gather information to determine the most probable and desirable futures of their system.

- Integration of learning: Participants combine information from the world scan and the system scan to develop a realistic desirable future; participants identify constraints to the most desirable future and develop strategies to overcome any barriers to achieving the most desirable future.

A complete Search Conference requires an 18-24 working-hour commitment (normally spread over three consecutive days) by participants. However, due to the time constraints of modern agribusiness, a number of adaptations were made to address contingencies unique to the industry. Participants could only commit three hours to each workshop. Also, with no prior history of productive collaboration among the chile industry’s diverse sectors, it was assumed (in retrospect, correctly) that a slow, incremental and indirect process would be required to overcome this barrier. Thus, a series of workshops was designed with the conference tasks allocated into blocks that could be accomplished within three hours.

Workshop 1

- Study significant recent history of the world chile industry.

- Identify the most probable futures of the world and local chile industries.

- Identify the most desirable future of the New Mexico chile industry.

- Identify barriers to the most desirable future.

- Identify next steps.

Workshop 2

- Review the most desirable future and constraints.

- Develop strategies to overcome barriers to the most desirable future.

- Evaluate strategies.

- Identify next steps.

Workshop 3

- Review the global environment and update tasks to be addressed.

- Review/evaluate outcomes of workshops 1 and 2.

- Form working groups to address specific tasks.

- Establish priorities by working group.

- Develop broad strategy for moving forward.

Planning for the New Mexico Chile Industry

As the search process unfolded, participants’ awareness that something different was happening enabled them to set aside much of the bias that had caused prior attempts at collaboration to fail. Beginning with the breadth of a global perspective, the participants gathered and analyzed data and came to agreement on a wide range of scenarios that provided context and substance to the strategic planning activity. Data were gathered on the worldwide chile industry by asking participants to respond to the question: “What have you seen happen in the worldwide chile industry in the last 5-7 years that struck you as novel or significant?" Participants then were asked to answer the following question: “What is the most probable future of the chile industry in 2002?" The group agreed that “given increased pressure from open, global markets with excessively cheap labor, the New Mexico chile industry will not survive another 5-7 years without major production cost reductions and/or yield increases” (Diemer, 1998).

Later, participants were asked to answer the following question: “What is the most desirable future for the local chile industry in 2002?” In this case, the group agreed that the most desirable future would include a strong and profitable industry, stronger university/industry collaboration, increased profitable yields, pest pressure under control, and a globally competitive industry (Diemer, 1998).

After identifying the components of a desirable future for the industry, Search Conference participants completed a planning reality check. This involved identifying the major barriers to accomplishing the desirable future and developing strategies to overcome them. Awareness of the barriers and the strategies to overcome them became part of subsequent planning for achieving the “most desirable future.”

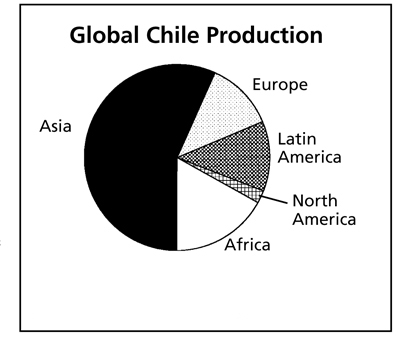

New Mexico Chile—A Small Niche in a Global Market

Chile is similar to many other horticultural niche crops grown across the United States. Viewed from a global perspective, it represents only a small fraction of worldwide production (fig. 2). Yet, chile production ranks first in horticultural crop cash receipts for New Mexico with annual direct contributions to the state’s economy of $60-100 million dollars (Gore, 1998).

North Americans tend to identify chile and related products with New Mexico. Chile salsas have replaced ketchup as the United State’s leading condiment (Weiss, 1997), and the demand for chile pepper products continues to grow. This phenomenon generates millions of dollars for the state’s economy directly, through the sale of chile, and, indirectly, through the sale of related goods and services by the state’s hospitality and tourism industries.

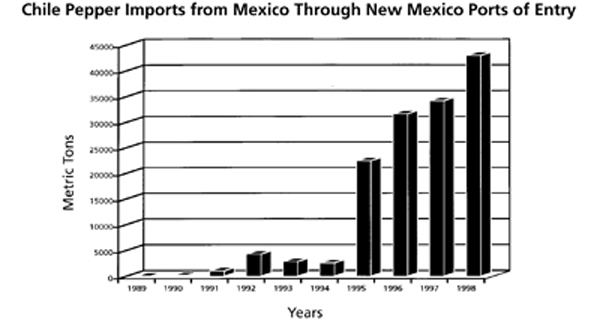

Figure 3. Fresh chile pepper imports from Mexico through Ports of Entry at Santa Teresa and Columbus, N.M. for 1989-1998 (Eastman and Orta, 2001).

The Chile Market Place’s Challenges

Chile’s growth in popularity is paralleled by growth in competition from alternative supply sources. “Old” Mexico currently provides New Mexico’s biggest competition for fresh chile sales in the U.S. marketplace. Fresh chile imports from Mexico into New Mexico have grown since 1989 (fig. 3). Imports from Mexico are expected to increase as tariffs are phased out by Aug. 1, 2003, to comply with NAFTA provisions (Eastman and Orta, 2000). To further complicate the future marketplace, chile imports from Africa, Asia, and other Latin American countries also are increasing (Biad, personal communication, 1999).

Global Trade and the New Mexico Chile Industry

Many sectors of the U.S. economy benefit from GATT, NAFTA, and the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) efforts to promote international free trade (Diemer, 1998 and 1999). However, as the dispute in Seattle at the 1999 WTO meetings (CNN, 1999) illustrates, there is no consensus among segments of the U.S. economy about how to implement these agreements. Certain sectors, particularly those that include hand-harvested, high-value, horticultural crops, feel endangered by global trade. For farmers in southern New Mexico’s chile-producing region, free trade is a hotly contested subject, and many voice concerns about their futures in the chile industry within the context of global free trade.

Chile Pepper Task Force — Work in Progress

Realizing the futility of challenging the trend toward global free trade, the Task Force opted to better use existing technologies and to develop new technologies to optimize industry profitability. Because a substantial portion of the cost of chile production is incurred by hand harvesting, the Task Force identified improving mechanical harvesting and cleaning equipment as a primary goal. Partnerships were developed with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Southwest Cotton Ginning Research Laboratory, the U.S. Department of Energy's Sandia National Laboratory, NMSU’s Manufacturing and Engineering Center (MTEC), and private mechanical harvesting equipment companies. Options being explored include adding compressed air or rakes to double-helix or overlapping-finger harvesters to lift chile off the ground prior to harvesting; and using sensors and feedback control to improve mechanical separation of trash from chile pods at the processing facilities.

Efforts also are underway to employ electronic telecommunications tools to assist the chile industry. A comprehensive Web site is being developed to provide up-to-date information and training. A lifelong commitment to learning is being fostered by developing distant learning workshops for growers and crop consultants. Personal data assistants (PDAs) are being tested for their use in improving record keeping and access to information. Focused data, delivered in an appropriate format, is one of the key tools that chile growers need to stay competitive in the rapidly changing world of global agriculture. The Task Force has initiated projects focused on developing these critical resources, and it is currently testing them to ensure that they meet constituents’ needs.

Initially, the Task Force established three work groups to move toward achieving the industry’s “most desirable future,” as identified by the Search Conference participants. These groups were to address best management practices and mechanical harvesting and drip irrigation technologies. Each working group established goals, set priorities and assumed responsibility for obtaining the resources needed to achieve its objectives. After an initial fact-finding period, the three groups were combined into one interdisciplinary group. This group meets monthly to evaluate progress on identifying and implementing best management practices, review progress on mechanical harvesting systems, share research information, and scan the chile world environment for opportunities to increase competitiveness.

Funding sources, including the New Mexico Chile Commodity Commission, USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS), USDA Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (CSREES), the chile processing industry, NMDA, chile growers and NMSU, have contributed more than $2 million to support the Task Force's efforts.

The Task Force also has served as an industry resource for the U.S. Department of Labor in its efforts to help growers and farm labor contractors comply with existing labor laws. It works with labor advocate groups to share information on the transition to mechanical harvesting and to help agricultural laborers find better employment. The Task Force also assists the NMDA in disseminating pesticide information and resolving pesticide-related issues, helping both the agency and the chile industry.

Discussion

Many U.S. horticultural niche industries, like the chile industry, are struggling to survive in a market that is rapidly evolving due to changes in international trade regulations, as well as domestic governmental and environmental pressures. The community referencing and search conferencing tools used by the Task Force may be adapted to benefit these industries. The community referencing process that identified and involved opinion leaders in the initial planning was critical. These leaders were able to work cooperatively to break the cycle of cynicism and pessimism and, instead, to focus attention on the available talent, resources and opportunities. The Search Conference process allowed diverse elements of the industry to discover areas of agreement and disagreement and to rationalize the areas of disagreement to form a sustainable relationship. It also empowered the participants to take control of their futures by learning to constantly scan their environment, evaluate new information, and devise and revise strategies to manage change in their industry.

Continued interdisciplinary involvement by growers, the processing industry, university research and Extension specialists, government agencies, agricultural product and service support companies, and various support organizations has kept the Task Force constructively challenged. Good ideas, potential funding sources and a solid commitment of resources have followed.

The Task Force’s ultimate test will be time. After three years, the group is adequately funded. Participants are focused and optimistic about the industry's future. Many challenges are ahead. The participant's continued willingness to work interdependently and to adapt to change ultimately will attest to the strength of the industry’s commitment to survive and prosper in a global economy.

1This article was reviewed by James D. Libbin, Professor, New Mexico State University, Department of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business;Thomas J. Dormody, Academic Department Head, NMSU Department of Agricultural and Extension Education; and Janet C. Brydon, Owner and Senior Editor, Edit Plus; all of Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Bibliography

Blick, Buzz. (n.d.). A briefing on the search conference method for participative planning. Retrieved Dec. 13, 2001

Cabana, Steven. (n.d.). The search for effective strategic planning is over. Posted Aug. 23, 1996. Retrieved Dec. 13, 2001.

CNN.com. (1999). Police, protesters look back on week of tear gas and trade meetings. CNN online News, posted Dec. 3, 1999. Retrieved Dec. 4, 2001, from http://www.cnn.com

Diemer, J.A. (1998). Search conference notes, general session, December 1998. (Available from International Institute for Natural, Environmental, and Cultural Resource Management, New Mexico State University, College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, Box 30003, Dept. 3169, Las Cruces, NM 88003-0003).

Diemer, J.A. (1999). Search conference notes, mechanical harvesting work group, 1999. (Available from International Institute for Natural, Environmental, and Cultural Resource Management, New Mexico State University, College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, Box 30003, Dept. 3169, Las Cruces, NM 88003-0003).

Diemer, J.A. and Alvarez, R.C. (1995). Sustainable community, sustainable forestry: A participatory model. Journal of Forestry 93(11), 10-14.

Eastman, C. and Orta, L.C. (in press). Farm labor dynamics in southern New Mexico: A trans-border phenomenon. Journal of Borderland Studies.

Gore, C.E. (1998). New Mexico agricultural statistics 1998. Las Cruces, N.M.: New Mexico Department of Agriculture.

Weiss, Michael J. (1997). The salsa sectors. The Atlantic Online, May 1997. Retrieved Dec. 13, 2001.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at aces.nmsu.edu

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

August 2002, Las Cruces, NM