RITF 85

Douglas S. Cram, Nicholas K. Ashcroft, Samuel T. Smallidge, and Les P. Owen

College of Agriculture, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Authors: Respectively, Assistant Professor/Extension Forestry and Fire Specialist, Range Improvement Task Force (RITF), New Mexico State University (NMSU); College Assistant Professor/Extension Range Management Specialist, RITF, NMSU; Associate Professor/Extension Wildlife Specialist/RITF Coordinator, RITF, NMSU; and Director of Conservation Services Division, Colorado Department of Agriculture. (Print Friendly PDF)

History of the National Environmental Policy Act

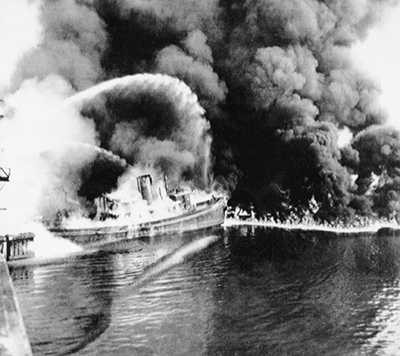

The introduction and timing of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) coincided with the beginning of the U.S. environmental movement in the late 1960s. In August of 1969, Time magazine ran a photograph of the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio, on fire (Figure 1). Even though the photograph was taken in 1952, and the Cuyahoga (and many other U.S. rivers) had caught fire several times in the past, the photograph and accompanying story epitomized the sensibilities of the environmental movement at the time (Adler, 2002).

Figure 1. A fire burns on the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1952. (AP Images)

The brainchild behind NEPA was a lifelong politician named Henry "Scoop" Jackson (1912–1983), a Senator from Washington. NEPA was enacted by the 91st Congress in 1969, and signed into law by President Nixon on January 1, 1970. It is one of the shortest laws on the books, spanning fewer than six pages.

Purpose of NEPA

As written, the purpose of NEPA was as follows:

- "To declare a national policy which will encourage productive and enjoyable harmony between man and his environment;

- To promote efforts which will prevent or eliminate damage to the environment … and stimulate the health and welfare of man;

- To enrich the understanding of the ecological systems and natural resources important to the Nation; and

- To establish a Council on Environmental Quality [CEQ]." (NEPA § 2)

NEPA covers all federal agencies and actions. Ideally, NEPA was designed to be a planning and decision-making process that considers biological, physical, economic, and social effects on the "quality of the human environment" (The Shipley Group, 2010). In layperson's terms, NEPA requires all federal agencies to take a "hard look" at how their actions affect the human and natural environment and if there are ways to minimize environmental effects.

"NEPA's purpose is not to generate paperwork—even excellent paperwork—but to foster excellent action. The NEPA process is intended to help public officials make decisions that are based on understanding of environmental consequences, and take actions that protect, restore, and enhance the environment." (CEQ Regulations § 1500.1[c])

Kershner (2011) characterized the early years of the act as follows:

"People were slow to realize the act's import partly because much of its language was purposely general. It was, as Jackson intended, a statement of broad policy, with passages more poetic than legalistic, such as 'enjoyable harmony between man and his environment,' and 'a wide sharing of life's amenities' (NEPA statute). One federal judge later called it 'almost constitutional' in its breadth and lack of specificity and another called it 'so broad, yet opaque' (Liroff, p. 5)."

and,

"Yet environmental activists didn't take long to notice that the Environmental Impact Statement provision could be NEPA's most potent tool. ... Within a few years, environmentalists had filed an avalanche of lawsuits which delayed or halted federal projects ranging from canals to oil pipelines to atomic power projects, on the basis that the required Environmental Impact Statement was either flawed or nonexistent. By 1975, the Army Corps of Engineers had claimed that 'NEPA had been responsible for modifications, delays or halts in 350 of its projects' (Liroff, p. 211)."

What "Triggers" NEPA?

Federal agencies must prepare a "detailed statement" (i.e., an Environmental Impact Statement) when "major federal actions" might "significantly [affect] the quality of the human environment" (NEPA § 102 (C)). Examples of federal actions include new or continuing projects on federal lands (e.g., new timber sales or renewing grazing permits). The next question becomes, what constitutes "major" and "significant"? The official language guiding this question states:

- "A 'Major Federal action' includes actions with effects that may be major and which are potentially subject to Federal control and responsibility." (CEQ Regulations § 1508.18)

- "'Significantly' as used in NEPA requires considerations of both context and intensity." (CEQ Regulations § 1508.27)

Regarding "context" and "intensity," the courts have ruled broadly on these two questions, and as a result the unofficial answer to the question is that the decision is often largely subjective.

NEPA Roadmap

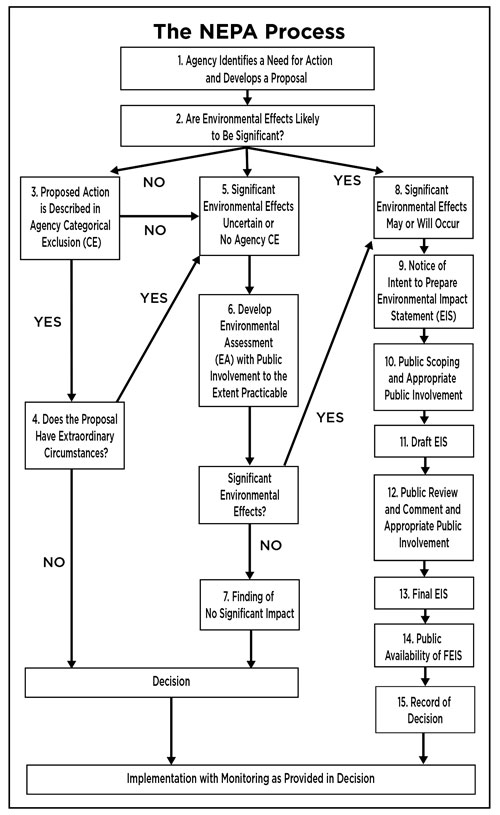

If a federal action is controversial or likely to have a "significant" environmental impact, then an Environmental Impact Statement followed by a record of decision is required. If the effect of the federal action is unknown or unlikely to have a "significant" environmental impact, then an Environmental Assessment and a finding of no significant impact are required. It is possible, however, that an Environmental Assessment concludes there will be a significant impact, in which case a subsequent Environmental Impact Statement will be required. A third option, known as a categorical exclusion, is reserved for rather specific actions that are known or have been shown to have no significant environmental impacts. See Figure 2 for a conceptual model of the NEPA process.

Figure 2. Flow chart model for the NEPA process (from Council on Environmental Quality, 2007).

The law is process oriented. It requires that federal agencies develop and follow a process to evaluate proposed federal actions in part through guidance provided by the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ). The CEQ—headquartered in the Office of the President of the United States—allows agencies to develop their own NEPA analysis processes to meet each agency's independent statutory obligations (Council on Environmental Quality, 2013). Generally speaking, the processes are similar among agencies. See NEPA.gov for a current listing of individual federal agencies and their specific NEPA procedures.

Environmental Impact Statement Requirements

Section 102 (C) of NEPA lists five requirements for an Environmental Impact Statement. They include a through description and discussion of 1) direct and indirect environmental impacts, 2) adverse and beneficial effects, 3) alternatives, 4) short- and long-term effects and relationships (i.e., cumulative effects), and 5) irreversible and irretrievable commitments of resources. The final requirement is full disclosure of all impacts to all interested parties, and subsequently providing an opportunity for them to make and submit comments.

Evaluation Criteria

Section 102 (B & C) of NEPA outlines evaluation criteria that must be considered in the decision-making process. These include environmental impacts as well as technical and economic considerations. In addition, the following circumstances have been known to influence the final decision: the agency's legal mission, budgets, stakeholder values, agency policy and traditions, as well as personal values of the decision maker (The Shipley Group, 2010). It is important to note that a federal agency can make a decision that significantly affects the environment as long as it has fully complied with NEPA procedures and requirements and no other laws are violated (e.g., military maneuver sites).

"...it is now well settled that NEPA itself does not mandate particular results, but simply prescribes the necessary process. ... If the adverse environmental effects of the proposed action are adequately identified and evaluated, the agency is not constrained by NEPA from deciding that other values outweigh the environmental cost. ... Other statutes may impose substantive environmental obligations on federal agencies, but NEPA merely prohibits uninformed—rather than unwise—agency action. [emphasis added]" – Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council (1989)

NEPA only requires that federal agencies consider the impacts of their actions on the human and natural environment. No mandate exists for agencies to minimize negative or maximize positive environmental impacts of their proposed actions—only that they consider them.

Public Involvement

"Citizens often have valuable information about places and resources that they value and the potential environmental, social, and economic effects that proposed federal actions may have on those places and resources. NEPA's requirements provide you the means to work with the agencies so they can take your information into account." (Council on Environmental Quality, 2007, p. 1)

All citizens have the opportunity to get involved in the process for all federal actions considered under NEPA. Participation may occur by attending public meetings regarding specific proposed federal actions, and commenting on draft Environmental Impact Statements and Environmental Assessments. Proposed federal actions are published in draft form in the Federal Register, where information regarding the proposed actions and decisions of the federal government is posted daily. Individuals can sign up to receive daily updates of the Federal Register Table of Contents at https://www.federalregister.gov/my/subscriptions/new.

Perspective

As a result of broad language and subsequent broad interpretation by the courts, NEPA draws considerable power from its ongoing case law history. Because of the inherent subjectivity in the decision-making process, the question becomes whose values will be taken into consideration? Stakeholder input is an important part of the NEPA process, and it is essential to participate in order to make your voice heard

References

Adler, J.H. 2002. Fables of the Cuyahoga: Reconstructing a history of environmental protection. Faculty Publications, Paper 191. Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University School of Law.

Council on Environmental Quality. 2007. A citizen's guide to the NEPA: Having your voice heard. Washington, D.C.: Author.

Council on Environmental Quality. 2013. NEPA and NHPA: A handbook for integrating NEPA and Section 106. Washington, D.C.: Author. Available at http://www.achp.gov/docs/NEPA_NHPA_Section_106_Handbook_Mar2013.pdf

Kershner, J. 2011. NEPA, the National Environmental Policy Act [Online]. HistoryLink.org. Available at http://www.historylink.org/File/9903

Liroff, R. 1976. A national policy for the environment: NEPA and its aftermath. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council, 490 U.S. 332. 1989.

The Shipley Group. 2010. Introduction to the NEPA process, 2nd edition. Farmington, UT: The Shipley Group, Inc.

For further reading

RITF 82: Elk and Livestock in New Mexico: Issues and Conflicts on Private and Public Lands

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_ritf/RITF82.pdf

RITF 83: Wilderness Designation and Livestock Grazing: The Gila Example

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_ritf/RITF83.pdf

RITF 84: Scientific Review of December 14, 2010, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Proposal to List the Dunes Sagebrush Lizard as Endangered Under the Endangered Species Act

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_ritf/RITF84.pdf

Douglas Cram is a College Assistant Professor at New Mexico State University. He earned his Ph.D. at New Mexico State University. His research and Extension programs focus on forestry and fire ecology in the Southwest.

To find more resources more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced, with an appropriate citation, for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

March 2017 Las Cruces, NM