Guide I-117

Douglas Cram, Suzanne DeVos-Cole, Sidney Gordon and Gabe Kohler

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Respectively, Extension Forest and Fire Specialist at New Mexico State University; Mora Country Cooperative Extension Agent; Otero County Cooperative Extension Agent; and Southwest Program Manager at Forest Stewards Guild. (Print-Friendly PDF)

Introduction

In what has become a recurrent scenario across the West, unabated wildfires threaten lives and human values as they move across the landscape. When it comes time to evacuate a home, apartment, or residence due to the threat of an impending wildfire, there is often little time to contemplate what to take and what to leave; in some worst-case scenarios, there is simply no time at all. This scenario can be stressful and potentially life-threatening. As such, it becomes difficult to make rational and thoughtful decisions in the face of fear, uncertainty, and haste. This circumstance is further complicated by humans’ tendency to question sometimes whether even to evacuate their dwelling in the first place. Generally speaking, this situation is not a scenario individuals have extensively planned for in order to act decisively at a moment’s notice.

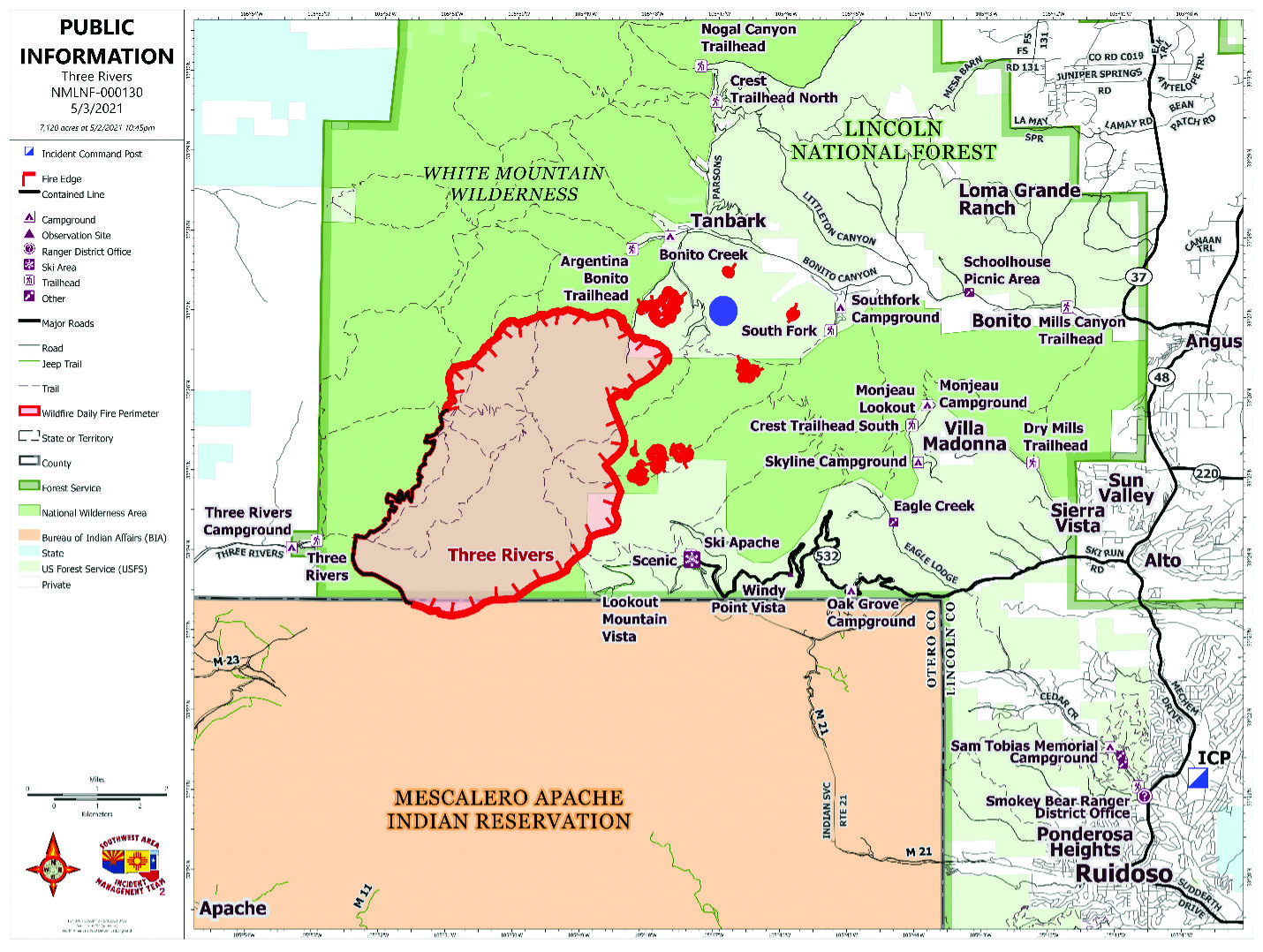

Figure 1. Three Rivers wildfire map from May 3rd, 2021. Notice the numerous spot fires (depicted generally as red circles) burning out ahead (to the northeast) of the main body of fire. The wildfire was driven by southwest winds. Hypothetically, imagine a dwelling located in the blue circle. Then, imagine occupants planning to evacuate if and when a wall of flames approached from the southwest (knee-jerk thinking). However, given the location of the spot fires, entrapment from multiple growing and converging spot fires would be inevitable. Takeaway message: evacuate early.

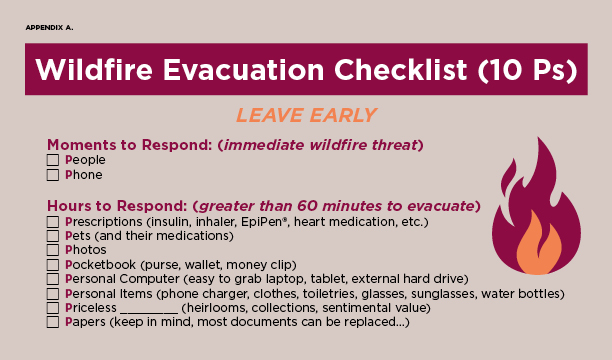

This publication has two goals: 1) proactively prepare and educate readers on what to consider in the event of a wildland fire evacuation from a dwelling, and 2) provide a simple checklist of material items to use when evacuating a dwelling due to wildfire (that does not require reading the publication to use or understand). By providing a structured checklist (see Appendix A), this publication is designed to help mitigate panic and increase efficiency when evacuating a dwelling due to wildfire (or other natural disaster). To facilitate efficiency, the checklist has been designed as an alliteration of the letter “P” to serve as a catchy reminder if the checklist is not physically in hand during an evacuation. By following the checklist, individuals will be systematically guided through a list of material items, thereby facilitating decisions as well as calming nerves (i.e., pets, photos, and “priceless” items). This structured approach will help evacuees make efficient and thoughtful decisions in a stressful environment. Secondarily, this publication is designed to highlight and discuss proactive planning tips to reduce panicked behavior while minimizing painful loss outcomes.

Ready, Set, Go – New Mexico

The Ready, Set, Go - New Mexico publication is designed as a wildland fire action guide (found online by searching “ready set go New Mexico”). It is a comprehensive guide tailored for New Mexico that outlines specific actions during a wildland fire event. For example, the guide establishes actions to take leading up to 1) a wildland fire event (READY), 2) when wildland fire is imminent (SET), and 3) when it is time to evacuate (GO). The 10 Ps checklist provided in this publication is meant to complement the Ready, Set, Go guide. In particular, the Ready, Set, Go guide does not provide a checklist of material items individuals may wish to collect prior to evacuation.

WILDFIRE EVACUATION CHECKLIST – THE 10PS

Moments to Respond (immediate wildfire threat)

People – Prioritizing people needs no explanation. Consider individuals with special needs (e.g., walker, wheelchair, child car seat, etc.) and how their circumstances may require specific vehicles and additional loading times. As conditions safely allow, consider checking on elderly and homebound neighbors and inquire about their evacuation plans; lend a helping hand as appropriate. Improvisation may be required in an emergency to overcome obstacles and challenges quickly. In a worst-case scenario, seconds and minutes can make the difference between escape and entrapment. Resist the urge to gather up material goods and evacuate immediately.

Phone – A mobile phone can be a vital communication tool in emergencies. Smartphones, in particular, provide multiple lines of communication (e.g., phone call, text message, e-mail, social media posting). In some locations and terrains, sending and receiving a cellular text message is possible, whereas placing or receiving a cellular phone call is not. Further, some phones and apps allow real-time tracking. These features facilitate evacuation navigation or help first responders find stranded or entrapped individuals. Remember, it is not uncommon for communication lines to be knocked out of service and inoperable during a disaster. Seconds and minutes can make a difference in emergency evacuation situations, so do not spend too much time looking for a phone. Proactive tip: Most smartphones have global positioning system (GPS) capabilities that can be used even if a cellular or Wi-Fi signal is unavailable. However, fully utilizing this capability usually requires using particular apps that need to be downloaded and activated (e.g., Avenza Maps™, Family Sharing on iPhone, etc.), preferably prior to the onset of a disaster.

Hours to Respond (greater than 60 minutes to evacuate)

Prescriptions/Medications – Consider what medications are needed daily that cannot be easily or quickly replaced (e.g., insulin, inhaler, EpiPen®, heart medication, etc.). As time and practicality allow, medical devices might also be considered in some cases. It could be days before officials allow individuals to return, and even then, nothing may be standing upon return. A four to seven-day supply of medications is recommended. Proactive tip: Prepare a prescription/medication grab-bag ahead of time, thereby simplifying this step in an emergency.

Pets – Lost pets and pictures are the top two items cited by individuals experiencing fire loss as things they wish they could get back. Evacuating pets may be as trivial as grabbing animals (and their medications) and heading out. However, as the size and number of pets increase, so does the complexity of the operation. For example, multiple pet carries and a pickup truck may be required. As previously noted, do not spend inordinate amounts of time looking for pets or coaxing them out of hiding; this is a documented cause of previous evacuation fatalities. Proactive tip: Prepare a pet evacuation plan and consider the following: 1) a four-to-seven-day supply of prescription medications, food, and water (don’t forget feeding and drinking bowls); 2) collar and leash; 3) vaccination record as most shelters and boarding facilities require evidence of shots; and 4) pictures of pets in case they get lost.

Photos – As time permits, grab a few photos off the wall, or albums off the shelf (e.g., wedding, children, trips, special occasions, etc.). As noted above, the loss of photos is frequently cited as significantly missed items. Proactive tip: Digitize your favorite photos (or all if you prefer). While many photos taken “today” are in a digital format, others taken “yesterday” are not. However, “there’s an app for that.” One option is Google’s PhotoScan. This app is designed to produce a high-quality digital image from a hardcopy picture (i.e., a picture of a picture). Likewise, there are relatively affordable options to digitize prints, slides, and negatives. Another proactive tip is to store these digital images in two locations (e.g., on your phone but also online, away from the reach of a destructive wildfire, thereby providing some peace of mind during an evacuation). If the thought of backing up all your photos is overwhelming, consider starting or prioritizing your top 50-100 photographs.

Pocketbook – For example, purse, wallet, money clip. Items in our pocketbooks, such as a driver’s license, government-issued identification, credit cards, and cash, are valuable items to have during an evacuation. Proactive tip: Inventory the contents of your pocketbook and e-mail the results to yourself. If your pocketbook is destroyed in a fire, you will at least have a list of what needs to be replaced.

Personal Computer – Our computers hold useful information and valuable files such as important documents, papers, contacts, passwords, and photos. Laptops, tablets, and external hard drives are easy items to grab; desktop units are more cumbersome but still relatively simple to move. Leave keyboards, monitors, and accessories, but remember to grab charging cables. Proactive tip: This might sound familiar: create a backup file online or “in the cloud” for important digital files stored on your electronic device.

Personal Items – For example, clothes for a week, toiletries, glasses, sunglasses and a water bottle. Also, remember to grab charging devices for electronics. If possible, wear long pants and a long-sleeved shirt made of 100% cotton to help protect skin from potential radiant heat. Synthetic fibers like nylon and polyester can melt. Leather gloves are also useful. A wool blanket or an insulated windshield sunscreen in the car can also drape over or shield people exposed to intense radiant heat.

“Priceless” ________ – You fill in the blank. Examples include jewelry, timepieces, furniture, recipes (hand-written), letters/diaries/scrapbooks, military memorabilia, china, quilts, books, collections (coins, stamps, baseball cards, records), wedding gowns, trunks and chests, musical instruments, embroidered linens, firearms, art, seeds, and anything else you like. Proactive tip: Take some time to identify and prioritize what is “priceless” and write it down on the wildfire evacuation checklist. Consider the size and space these items require for transportation and the time required to locate and load these items into a vehicle. Another proactive tip is to inventory your home contents. As you might suspect, “there’s an app for that” (e.g., Sortly, Memento Database, Nest Egg, MyStuff). Alternatively, or in addition, consider taking a one-minute video of each room in your dwelling with audio narration. Then e-mail yourself the short video; re-film rooms through time as contents change. While this proactive tip will not save content from burning, it will facilitate the claims process if the dwelling has an insurance policy. Speaking of dwellings and outbuildings with adequate insurance coverage, they can potentially provide some level of peace of mind in the event of an evacuation. However, check with your agent to see what is covered (and at what percent) and what is not in the event of a wildfire claim (and potential subsequent flooding).

Papers – Most documents can be replaced if necessary (e.g., government or agency-issued birth certificates, social security cards, property deeds, etc.). However, living and last will, power of attorney, revocable trust, and health care directives may be examples of documents that cannot be routinely or economically replaced if destroyed in a fire. Proactive tip: Create digital copies of important papers and store them in two locations (preferably one being online or “in the cloud”).Leave Early

Remember evacuation window estimates (especially those limited in nature, such as 30-60 minutes) provided by fire officials are best guesses and should be considered imperfect information. In addition, it is not uncommon for multiple evacuation orders to be issued, leading to potential confusion. Because time is limited, evacuees should efficiently complete the checklist and evacuate as soon as possible (i.e., leave early). In densely populated regions with limited egress routes, expect potentially slow evacuation times due to traffic backups; again, leave early. Upon evacuation, turn on vehicle headlights, drive cautiously, and remain calm to make rational decisions. Proactive tip: Be familiar with multiple evacuation routes. Online maps and satellite imagery can identify escape routes and options for off-road vehicles, horseback, or walking trails. The ability to leave early can also be facilitated by signing up for county and city emergency notification systems (e.g., reverse 9-1-1, CodeRed, Nixle.com). Search the Internet by county or city using keywords such as “alerts” and “emergency notification.” However, these systems are not foolproof. Accurate and precise information in an evolving emergency is not always possible.

Wildfire Movement across the Landscape

It is noteworthy to discuss and illustrate how wind-driven wildfires move and spread across the landscape. A common but incomplete thought is imagining a wall of flames marching steadily across a field or forest. This false narrative leads to a knee-jerk reaction, “I will evacuate when I see the wall of flames approaching.” In reality, wind-driven wildfires advance across the landscape through two simultaneous mechanisms: flaming fronts AND wind-blown embers (also commonly referred to as sparks, ashes, and firebrands). Because winds can carry and scatter these fire starters across the landscape, multiple “spot” fires can be generated simultaneously ahead of the so-called main fire. Spotting distances can range from feet to miles. Subsequently, many spot fires can grow larger and larger, sometimes converging and intensifying, creating an ever-changing fire footprint. Given sustained fuels and winds, the process repeats itself, and fire moves across the landscape, including forests and grasslands. This mechanistic movement can be seen in Figure 1. (Note: in extreme cases, an all-encompassing third mechanism contributes to fire spread: a pyro-cumulonimbus column of smoke, gas, air, and clouds reaching tens of thousands of feet into the troposphere driven by self-generating winds capable of causing mass incineration; see Figure 2).

What Not To Do…

There are numerous steps individuals can take to harden their dwelling and yard to the effects of wildfire and embers (e.g., FireWise® programs). However, these actions are most effective when used proactively in the years and months leading up to fire season, not in the minutes or hours before an evacuation. Likewise, do not plan to slow down a wildfire with a garden hose. Intense heat, toxic smoke, limited visibility, deafening winds, and flames will render this approach useless and dangerous.

Figure 2. A pyro-cumulonimbus column of smoke, gas, air, and clouds reaching tens of thousands of feet into the troposphere driven by rising heat from the fire and self-generating winds capable of causing mass incineration. Hermits Peak/Calf Canyon wildfire, spring 2022, New Mexico. Photo by Michael Benanav / Searchlight New Mexico.

Appendix A.

Douglas Cram is an Extension Forest and Fire Specialist at New Mexico State University. His research and extension efforts focus on management of forests, rangelands, and riparian areas with a particular concentration on the interaction of fire within these systems.

Suzanne DeVos-Cole is an Extension Agent for Mora County at New Mexico State University. She received her MLA from the University of Pennsylvania in landscape architecture. Her Extension program focuses on improving the quality of life for her constituents in the areas of 4-H and youth development, agriculture, and family and consumer sciences.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu.

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced, with an appropriate citation, for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

May 2024 Las Cruces, NM