Guide H-188

Geraldine Diverres, Markus Keller, Michelle M. Moyer

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Authors: Respectively, Extension Viticulturalist Specialist, Department of Extension Plant Sciences, College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University; Professor in Viticulture, Department of Viticulture and Enology, Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center, Washington State University (WSU); and Professor and Viticulture Extension Specialist, Department of Viticulture and Enology, Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center, WSU. (Print-Friendly PDF)

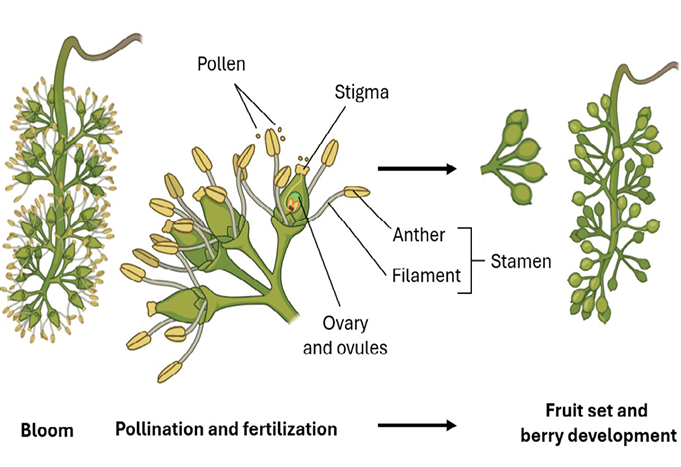

Figure 1. Graphical summary of the processes of bloom, pollination and fertilization in grapes. In grapevines, several hundred flowers are grouped into a cluster called an inflorescence. Most cultivated varieties have flowers containing both male and female reproductive organs and are self-fertile. In spring, these organs mature shortly before the flower caps (calyptra) are shed (bloom), exposing the anthers and stigma. Pollen released from the anthers lands on the stigma (pollination), germinates, and forms a tube that delivers sperm cells to the ovary (fertilization). A successful fertilization triggers hormonal signals that drive the growth of the ovary walls to form the grape berry flesh, completing the transformation from flower ovary to fruit (fruit set). Graph created with BioRender.

Key information

- Fruit set is the transformation of flowers into grape berries following pollination and fertilization. Fruit set plays an important role in determining final vine yield in that growing season.

- Not all flowers turn into berries, and this is considered normal. However, fruit set is considered low when less than 30% of flowers become berries. Poor fruit set can be a consequence of many factors including adverse weather or imbalances in vine physiology due to biotic or abiotic stress.

- The effectiveness of vineyard management practices to improve fruit set is limited by environmental and genetic factors.

Introduction

Fruit set is a key developmental stage in seasonal grapevine growth. This stage refers to the transformation of flowers into berries following pollination and fertilization (Figure 1). The success of the flowering process, in combination with the number of flowers that were on a vine before bloom and the extent to which the berries grow after fruit set, determines crop yield. Disturbances in bloom, pollination, or fertilization (which reduce fruit set) can therefore negatively impact yield.

What is poor fruit set?

On average, only 30 to 50% of the flowers within an inflorescence will become berries; the rest fail to set fruit and drop off.1 Vines with more clusters or with clusters that have more flowers tend to exhibit naturally lower fruit set rates. When fruit set rates fall below the normal range for a particular variety, the condition is called shatter or poor fruit set. This situation becomes problematic when it leads to a significant reduction in yield (Figure 2). However, low fruit set does not always mean low yield. Grapevines can offset–to a certain degree–low fruit set through increased berry size, an adaptive mechanism known as yield component compensation.

Figure 2. Low fruit set or shatter in Vitis vinifera cvs. Chardonnay (top) and Cabernet Sauvignon (bottom) clusters. When many unfertilized, dried-up flowers remain attached to the clusters, such flower debris can provide entry points for the Botrytis bunch rot fungus. Photos by M. Moyer and G. Diverres.

However, high fruit set is not always desirable. Certain varieties tend to produce inflorescences with many flowers and have high fruit set. The resulting clusters may have berries tightly pressed together and can suffer from uneven ripeness and berry splitting, which can increase the risk of harvest rots.

What causes poor fruit set in the vineyard?

Some growing seasons will present environmental challenges beyond a grower’s control, while others may expose inadequate vineyard management practices that can be addressed and improved. This document groups the causes of poor fruit set into three main categories:

- Genetic factors – Factors intrinsic to the variety or rootstock, like the number of clusters on a shoot, flowers in a cluster, or the drought and salinity tolerance.

- Weather limitations – Factors that are largely outside the grower’s control, such as adverse weather conditions like rainfall, cold temperatures, or heatwaves.

- Physiological and management derived causes – Internal vine processes influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, as well as controllable decisions around vineyard management practices.

Genetic factors

Genetic factors are characteristic of a given variety, clone, or rootstock. Cultural practices allow us to manage these traits to optimize productivity, but they cannot be modified. They play a role in determining the maximum number of clusters a shoot can bear or flowers a cluster can bear. Certain Vitis vinifera varieties like Grenache, Malbec, or Merlot can experience fruit set problems frequently.2 Other varieties have a naturally low number of berries because they produce fewer flowers, like Tempranillo, Sauvignon blanc, Pinot noir, or Chardonnay.3 Conversely, some varieties may have a higher number of flowers but lower rates of fruit set (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Genetic differences affect the number of flowers produced per inflorescence. Chardonnay (left) is a variety that typically produces a low number of flowers but has a high percentage of fruit set as opposed to Cabernet Sauvignon (right). Photos by M. Keller.

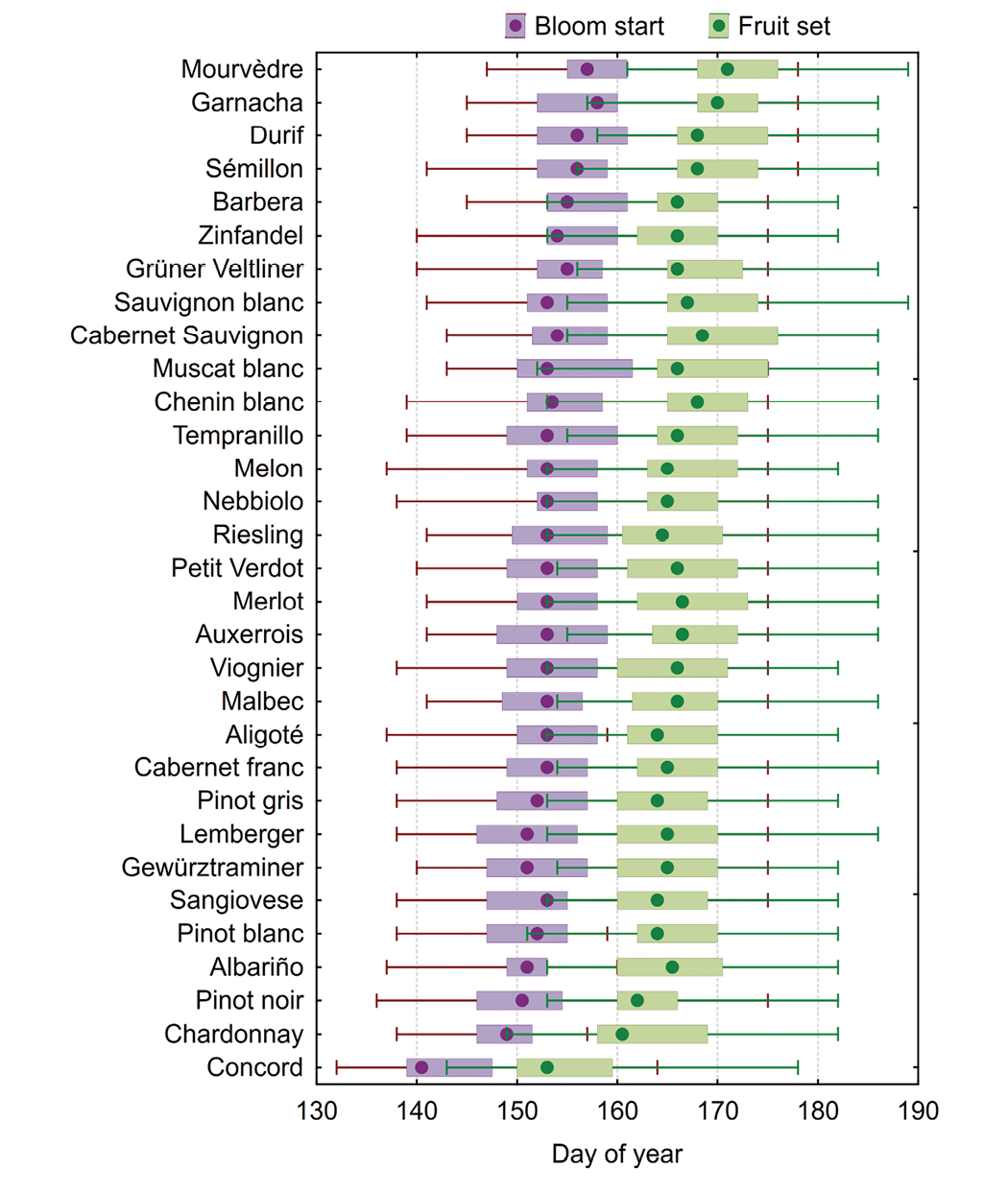

What to do in the vineyard: Before planting, match site and variety. Avoid selecting grape varieties that tend to bloom during high-risk weather periods in your region (Figure 4), like spring frost, heat spikes, rain, or extreme winds, which are common in the growing regions of New Mexico. Rootstock selection should also be considered, since the rootstock can impact fruit set indirectly by increasing sensitivity to drought, salinity or by performing poorly in alkaline soils, like Riparia gloire (RG) or 101-14 Mgt. Paulsen 1103, on the other hand, has been reported to show tolerance to drought and high pH (above 7.5) soils.4

Figure 4. Dates for the beginning of bloom (purple) and fruit set (green) for 31 own-rooted grape varieties grown in Prosser, (eastern) Washington. Despite coming from a different region, the relative dates of bloom and fruit set between varieties can be used to guide planting decisions in New Mexico. Each box shows the usual range of bloom and fruitset dates observed over several growing seasons (2015–2024). The dot represents the average timing, while the box and lines show how much those dates can vary from year to year due to environmental conditions. Figure by M. Keller.

Weather limitations

Weather is one of the most influential and least controllable factors affecting fruit set. The timing and severity of inclement weather will determine the degree of impact. Temperatures below 59°F (15°C), overcast skies, and heavy rains or winds can reduce fruit set by hampering cap fall, pollination, and/or fertilization (Figure 5). Temperatures above 95°F (35°C) are equally detrimental to these processes. Cold stress or low light before or during bloom can starve the flowers of vital carbohydrates, and heat stress can dehydrate the flowers, causing them to drop from the inflorescence.5

What to do in the vineyard: Before planting, it is essential to choose a suitable vineyard site. Avoid locations prone to frost pockets, excessive shade, or high winds. Vineyard design should also support healthy canopy development through appropriate row spacing, orientation, and trellis systems that maximize sun exposure and airflow.

Once the vineyard is established, growers have limited options to mitigate the effects of adverse weather during bloom. Delaying the time of winter pruning closer to budbreak (late pruning) can improve fruit set if it pushes phenology to optimal weather conditions during bloom.6 This delay is variable, and success still depends on the variety and the weather conditions that year. Late pruning should be exercised with caution, as pruning too late (7 leaves unfolded in the two top buds per retained cane or later) could leave vines depleted of carbohydrate reserves, which may exacerbate the impact of poor weather on fruit set.7 If adverse weather is forecasted at the time of bloom, shoot tipping (removing only the shoot tips, not hedging) may also help to improve fruit set by temporarily eliminating the highly competitive shoot tips. This strategy helps to redirect the vine’s limited carbohydrates towards the comparatively weaker flowers. However, if tipping is done too early, lateral shoots will grow and create new competing shoot tips.

Figure 5. A trial in a Cabernet Sauvignon vineyard in Prosser, Washington, demonstrated how cool inflorescence temperatures during bloom (average 61°F) retarded and reduced fruit set (left) compared to warm conditions (average 70°F; right). Photos from Keller et al. (2022).8

Physiological and management derived causes

Even under optimal weather conditions, fruit set can still be compromised by a range of physiological imbalances and vineyard management practices. Nutrient deficiencies, water stress, hormonal imbalances or poorly timed cultural practices can all impair fruit set. In addition, external pressures like pesticide damage, or pests and diseases can further disrupt the reproductive success.

- Pruning practices:

Retaining a high number of buds (e.g., through mechanical or minimal pruning) often leads to lower fruit set rates because the available resources early in the season are spread across a larger number of growing shoots and clusters (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The effect of pruning severity on fruit set in a Merlot vineyard in Prosser, Washington. More retained buds in a minimally pruned vine led to more clusters and reduced fruit set (left), as opposed to a spur-pruned vine with fewer retained buds and hence fewer clusters and higher fruit set (right). Photos by M. Keller.

What to do in the vineyard: Increasing the pruning severity (i.e., leaving fewer buds per vine) increases the carbohydrates and other nutrients available per shoot and cluster, which can increase fruit set. Balanced pruning aims to retain about 15 buds for each pound of pruned canes.

- Carbon starvation

Poor fruit set is often linked to low carbohydrate availability. When reserves are insufficient, the vines struggle to support developing flowers and become more vulnerable to unfavorable weather and to conditions that limit photosynthesis (Figure 7). Similarly, a low leaf area (less than about 1 square inch, <5 cm2, per flower) also limits photosynthesis and carbon availability9 (Figure 8). The result is competition between flowers and growing shoots, pulling resources away from the flowers and reducing fruit set. Excessive vine density, inadequate trellising, or improper canopy management can also result in leaves and inflorescences that are shaded or cannot meet the vine’s requirements (Figure 9). These shaded clusters are prone to drop more flowers.10

What to do in the vineyard: Ensure the development of a functional canopy early in the season. Establishing an optimal leaf area quickly in spring ensures vines have enough photosynthetic capacity to support the development of flowers and their transformation into fruit. If low fruit set has been a concern, delay leaf removal until after fruit set to preserve photosynthetically active leaf area and support the processes of flowering and fruit set. Focus on creating a sun-exposed fruiting zone through thoughtful shoot thinning and leaf removal practices that enhance light penetration without compromising vine energy reserves.

Figure 7. Excessive loss of flowers or entire branches of the inflorescence is known as inflorescence necrosis or early bunch stem necrosis. Cool temperatures and overcast skies, water and/or nutrient deficiencies before bloom reduce the sugar available to flowers. This photograph shows the effect of overcast skies during bloom combined with competition from under-vine vegetation in a nitrogen-deficient vineyard. Photo from Keller et al. (2001).11

Figure 8. Fruit set is compromised when the canopy fails to meet the requirements of the developing flowers. This problem is worsened by low carbohydrate reserves and adverse weather conditions. The photograph shows the effect of low leaf area of the shoot in the front, while the shoot in the back had adequate leaf area. Photo from Keller et al. (2010).12

Figure 9. Insufficient or poorly timed shoot thinning, overcrowded canopies, or low light exposure can reduce the vine’s photosynthetic capacity and flower viability. Early leaf removal (during bloom) can compromise fruit set by reducing the photosynthetic leaf area at a time when the developing inflorescences are competing with growing shoot tips for limited resources. This photograph shows the results of a leaf removal experiment with vines defoliated at 100% bloom (left) versus a no defoliation control for reference (right). Photos by Michelle Moyer.

- Water stress and nutrient deficiencies

Moderate or severe water stress during the period leading up to and during bloom interferes with flower and pollen production, pollination, and fertilization.

Water stress decreases photosynthesis and the availability of carbohydrates. When water stress is combined with nutrient deficiencies, the result is an even more drastic reduction in fruit set and yield (Figure 10). The success of pollination and fertilization depends on the presence of macro- and micronutrients, all of which should be in adequate supply to ensure overall vine health and reproductive performance. In some cases, excess will be as detrimental as a deficiency.

Figure 10. An experiment with potted Cabernet Sauvignon vines showed the drastic reduction in fruit set when water and nutrient deficiencies are combined (left) as opposed to just the effect of water deficit alone (right). Photo from Keller (2025).13

The nutrients associated with reproductive success are nitrogen, calcium, boron, zinc, and molybdenum. Their deficiency has been linked with the incidence of “hens and chicks” (Figure 11), a disorder characterized by clusters containing a mix of normal, seeded berries (the “hens”), and smaller berries with seed traces (the “chicks”), and often unfertilized and seedless berries, more accurately referred to as live green ovaries. Though fruit set seems normal, the live green ovaries, which are essentially unfertilized flowers that fail to abort, do not develop into berries and do not accumulate sugars or undergo ripening. This condition can result from a combination of factors aside from nutrient imbalances, including early-season water stress, and poor weather conditions at bloom.

Figure 11. “Hens and chicks”, also known as millerandage, in two clusters photographed at different phenological stages. Photos by M. Keller.

What to do in the vineyard: In arid regions where soil moisture is controlled through irrigation, do not impose deficit irrigation until after fruit set. Irrigate if soil moisture is below 35% of extractable soil water content at the beginning of the growing season or as soon as water is available.14 The extractable soil water content is a unit that refers to the soil moisture available for plant water uptake. It includes the soil moisture content at field capacity and permanent wilting point. Because it accounts for these two reference points that are unique to every soil type, it provides a consistent and comparable measure of plant-available water across different soils, regardless of their characteristics. The extractable soil water content can be calculated as15:

- Pests and diseases

Pests and diseases can negatively impact fruit set by causing direct damage to flowers or reducing functional leaf area, particularly when it occurs early in the growing season (Figure 12). The grapevine western leaf skeletonizer (Harrisima brillians, H. metallica), grapevine leaf hoppers (Erythorneura elegantula, Erythorneura spp.) and the grape flea bettle (Altica chalybea, Altica spp.). Pests and diseases can also indirectly impact fruit set by causing generalized vine decline, physiological stress, foliage damage, or by feeding on the root system and limiting nutrient and water uptake.

What to do in the vineyard: Implement integrated pest management (IPM) strategies and site-adapted weed control to maintain vine health and reduce competition for water and nutrients. For further reading on IPM strategies specific to NM, please visit: Grape Integrated Pest Management in NM: https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_circulars/CR705/index.html

Figure 12. Examples of early-season leaf damage caused by common insect pests in NM vineyards. From left to right: feeding damage caused by grape leaf skeletonizer; leafhoppers; and grape flea beetle. Early-season injury can reduce leaf area, reducing the photosynthetic capacity if pest pressure is high. Correct identification of damage patterns is important for timely scouting and management decisions.

Summary

Fruit set in grapevines is influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, and vineyard management practices. While some causes of poor fruit set are not yet fully understood and may result from a combination of stressors, environmental conditions that reduce fruit set often do so by inducing carbon starvation. The strategies to improve fruit set are generally aligned with those that promote vine balance, the early development of functional canopy and higher photosynthetic rates. A healthy, open and sun-exposed canopy with sufficient leaf area, a balanced crop load, and an adequate irrigation and nutrition program creates the best conditions for a successful fruit set.

|

Table 1. Summary of management practices to favor fruit set in established vineyards. |

|---|

|

Prune according to vine size. |

|

|

Ensure adequate water and nutrient availability. |

|

|

Ensure the development of a functional canopy with adequate leaf area. |

|

Glossary of terms

- Biotic/Abiotic stress: Biotic stress refers to stress caused by living organisms, such as insects, bacterial and fungal disease agents, nematodes, or weeds. On the contrary, Abiotic stress refers to stress caused by non-living factors, including drought, heat, frost, salinity, nutrient imbalances, etc.

- Field capacity: The amount of water held in the soil after excess water has drained away. Field capacity depends on soil characteristics and varies by soil type.

- Permanent wilting point: The soil moisture level at which vines and other plants can no longer extract water from the soil, resulting in permanent wilting. Water at this level is held too tightly by the soil to be used by plants. Permanent wilting point depends on soil characteristics and varies by soil type.

- Phenology/phenological stage: The timing and progression of recurring vine growth stages such as budbreak, bloom, fruit set, veraison, or leaf fall. These developmental stages are highly influenced by weather and environmental conditions.

References

- May, P. (2004). Flowering and fruitset in grapevine. Phylloxera and Grape Industry Board of South Australia in association with Lythrum Press.

- Zapata, C., Delée, E., Chaillou, S., & Magné, C. (2004). Mobilisation and distribution of starch and total N in two grapevine cultivars differing in their susceptibility to shedding. Funct Plant Biol, 31(11), 1127-1135. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP04028

- Dry, R., Longbottom L., McLoughlin S., Johnson E., & Collins, C. (2010). Classification of reproductive performance of ten winegrape varieties. Aust J Grape Wine R, 16, 47-55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0238.2009.00085.x

- Chen, Y., Fei, Y., Howell, K., Chen, D., Clingeleffer, P., & Zhang, P. (2024). Rootstocks for grapevines now and into the future: selection of rootstocks based on drought tolerance, soil nutrient availability, and soil pH. Aust J Grape Wine R, 2024(1), 6704238. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/6704238

- Greer, H., & Weston, C. (2010). Heat stress affects flowering, berry growth, sugar accumulation and photosynthesis of Vitis vinifera cv. Semillon grapevines grown in a controlled environment. Funct Plant Biol, 37(3), 206-214. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP09209

- Friend, A., & Trought, C. (2007). Delayed winter spurpruning in New Zealand can alter yield components of Merlot grapevines. Aust J Grape Wine R, 13(3), 157-164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0238.2007.tb00246.x

- Gatti, M., Pirez, F., Chiari, G., Tombesi, S., Palliotti, A., Merli, M., & Poni, S. (2016). Phenology, canopy aging and seasonal carbon balance as related to delayed winter pruning of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Sangiovese grapevines. Front Plant Sci, 7, 659. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00659

- Keller, M., Scheele-Baldinger, R., Ferguson, J., Tarara, J., & Mills, L. 2022. Inflorescence temperature influences fruit set, phenology, and sink strength of Cabernet Sauvignon grape berries. Front Plant Sci, 13, 864-892. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.864892

- Keller, M., & Mills, L. 2021. High planting density reduces productivity and quality of mechanized Concord juice grapes. Am J Enol Vitic, 72, 358-370. https://doi.org/10.5344/ajev.2021.21014

- Domingos, S., Scafidi, P., Cardoso, V., Leitao, A., Di Lorenzo, R., Oliveira, C. M., & Goulao, L. (2015). Flower abscission in Vitis vinifera L. triggered by gibberellic acid and shade discloses differences in the underlying metabolic pathways. Front Plant Sci, 6, 457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00457

- Keller M., Kummer M., Vasconcelos M.C. (2001). Reproductive growth of grapevines in response to nitrogen supply and rootstock. Aust J Grape Wine Res, 7, 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0238.2001.tb00188.x

- Keller, M., Tarara, J., & Mills, L. (2010). Spring temperatures alter reproductive development in grapevines. Aust J Grape Wine R, 16(3), 445-454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0238.2010.00105.x

- Keller, M. 2025. The science of grapevines. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2023-0-52580-7

- Diverres, G., Fox, D. J., Harbertson, J. F., Karkee, M., & Keller, M. (2024). Response of Riesling Grapes and Wine to Temporally and Spatially Heterogeneous Soil Water Availability. Am J Enol Vitic, 75, 0750019. https://doi.org/10.5344/ajev.2024.23073

- Groenveld, T., Obiero, C., Yu, Y., Flury, M., & Keller, M. (2023). Predawn leaf water potential of grapevines is not necessarily a good proxy for soil moisture. BMC plant biology, 23(1), 369. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04378-6

- Longbottom, M., Dry, P., & Sedgley, M. (2010). Effects of sodium molybdate foliar sprays on molybdenum concentration in the vegetative and reproductive structures and on yield components of Vitis vinifera cv. Merlot. Aust J Grape Wine Res, 16(3), 477-490. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0238.2010.00109.x

- Christensen, P., Beede, H., & Peacock, L. (2006). Fall foliar sprays prevent boron-deficiency symptoms in grapes. Calif Agric, 60(2). https://doi.org/10.3733/ca.v060n02p100

Geraldine Diverres Naranjo is the NMSU Viticulture Extension Specialist focused on irrigation management, vine physiology, and the effect ov vineyard management on fruit quality in arid climates.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu/

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

February 2026, Las Cruces, NM