Guide E-510A

Revised by Nancy Flores and Jay Lillywhite

College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University

Authors: Respectively, Associate Professor/Extension Food Technology Specialist, Department of Extension Family and Consumer Sciences; and Professor/Department Head, Department of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business, New Mexico State University. (Print Friendly PDF)

Introduction

Many people dream of owning their own food business and marketing a family recipe. How many times have you heard “You should sell this stuff”? Many large food businesses, such as Kraft, M&M/Mars, and Bueno Foods, started as small family enterprises. There are always opportunities for new food products in today’s marketplace. This publication, the first in a series on starting a food business in New Mexico, outlines the necessary steps to manage a food business and make that dream a reality. For more information on starting a food business in New Mexico, visit these resources:

- Guide E-510B: Starting a Food Business in New Mexico: Food Processing: https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_e/E510B/index

- Guide E-510C: Starting a Food Business in New Mexico: Food Safety: https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_e/E510C/index

Tobias Kleinlercher | Wikimedia Commons

Business Planning And Management

Successful new businesses require careful planning and management. Because businesses that produce and sell food can have a direct effect on public health and safety, they face increased government and consumer scrutiny. Food businesses must comply with numerous government regulations, making their development, operation, and success even more difficult.

Individuals interested in starting a food-processing business must gain a general understanding of business management issues before beginning a food-processing business. Additional and more specific information should be gathered from qualified professionals noted in the references section of this guide.

Business Structure

One of the first decisions an entrepreneur must make when developing a new business is which legal structure will be used for the business. A number of business structures should be considered, and each has advantages and disadvantages. Income tax advantages and/or limited liabilities are usually cited as a reason to prefer one form over another. The assistance of qualified tax and legal professionals can help entrepreneurs avoid many headaches and save some tax dollars. Some of the more common structures used in the food-processing industry are discussed below (U.S. Small Business Administration, n.d.), and include:

- Sole proprietorships

- Partnerships

- Limited liability companies and partnerships

- Corporations

- Cooperatives

Specific advantages and disadvantages of each of these business structures are discussed at the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) website at www.sba.gov, and are summarized here in Table 1. In addition, the SBA site provides other important tips for beginning a new business, including a 10-step checklist for starting your business (https://www.sba.gov/business-guide/10-steps-start-your-business).

|

Table 1. Abbreviated Summary of Business Structure Advantages and Disadvantages |

||||||

|

Ease of organization |

Control/management |

Liability |

Taxation |

Initial capital creation |

Continuity of life |

|

|

Sole Proprietorship |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

|

|

Partnership |

+ |

– |

+ |

+/– |

||

|

Corporation |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

||

|

Limited Liability Company |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|||

|

Cooperative |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|||

Sole proprietorships

Sole proprietorships are the most common form of business structure for small businesses. A sole proprietorship offers the owner (usually one individual who is responsible for routine operation of the business) complete control of the business. In reward for their efforts, the proprietor receives all business profits but assumes responsibility for all risks and liabilities. This responsibility extends to the owner’s personal assets; that is, the owner has unlimited liability and is legally responsible for all business debts. Both business and personal assets are at risk under the sole proprietorship form of business ownership and structure.

Partnerships

Partnerships, which include general (i.e., normal) partnerships, limited partnerships, and joint ventures, extend ownership from one individual to two or more individuals. Partnerships usually require shared management of the business, and should be created with specific agreements regarding the management of the business (e.g., how decisions will be made, how profits will be distributed, how disputes will be handled, and how future growth or termination will be handled). As with sole proprietorships, individual owners in a partnership are responsible for all company liabilities (relief from this personal liability is found in limited partnerships). In the case of a general partnership, individuals may also be responsible for the decisions and actions of other partners within the business as well.

Limited liability companies and partnerships

Limited liability companies and partnerships are hybrid forms of business ownership that combine the advantages of several different ownership structures. Specifically, they extend liability limitations (similar to those of a corporation) and maintain certain tax advantages of simpler structures (e.g., partnerships).

Corporations

A corporation is considered a separate entity from its owner(s). A corporation can be taxed or sued, it may enter into contractual agreements, and it has a perpetual life (its life is not affected by ownership). Shareholders of a corporation own the business, and management is generally performed by a shareholder-elected board of directors (who may elect a management team, e.g., president). Benefits of corporate structure include limited liability for owners (shareholders), perpetual life, ease of ownership transfer, and ease of capital acquisition. Disadvantages include possible higher taxes (taxes must be paid by the corporate entity and by shareholders from dividend distribution) and complexities of creation and maintenance.

Cooperatives

Often used by agricultural producers, cooperatives provide a unique business format that allows individual producers or processors to cooperate. Most cooperatives are organized as a special type of corporation “subchapter T” and must be chartered within a state. Common guiding principles for cooperatives include open membership with democratic or proportional voting (cooperative control), patron-provided equity, and net income distribution on a cost basis through patronage refunds (Barton, 1989).

A relatively recent advancement in cooperative organization is the development of “new generation” cooperatives. New generation cooperatives have several unique characteristics that distinguish them from more traditional cooperatives: delivery rights and requirements tied to equity investment, closed or limited membership, higher initial investment requirements, and the ability to transfer appreciable (and depreciable) stock or delivery rights (Bielik, n.d.).

Business Planning

In addition to determining the appropriate business or legal structure, food entrepreneurs must consider a number of other issues and develop management strategies for each issue. Feasibility studies and business plans are tools used by food entrepreneurs to develop working strategies.

Feasibility study

A feasibility study is a companion to the business plan (in some cases, such as small business ventures, the feasibility study is included as a section within the business plan). It is a preliminary analysis of the product and business idea to determine if the idea is viable (Reilly and Millikin, 1996). Information gathered in the feasibility study can be used to develop a formal business plan. A well-executed feasibility study will help determine if the product, the market, and the entrepreneur’s management skills and financing will likely combine to create a success. Common elements contained in a feasibility study include an assessment of the market, the financial feasibility of the business, and potential pitfalls that may be encountered in the development of the business.

Business plan

A business plan helps lay out the road map for a new (or existing) business. While plans for different business ventures will vary, all business plans should address:

- Business description and situation analysis

- Market analysis and planning

- Financing

- Management and human capital capacity

The business description and situation analysis should provide both the entrepreneur and potential outside stakeholders (e.g., partners, financial resource holders, etc.) a concise but complete description of the business. Included in this section should be a description and an analysis of the current business climate in which the new business will operate. Much of this information will have been obtained during the feasibility study.

The market analysis section of the business plan will continue with the work previously performed in the feasibility study. Specific considerations within this section will include a summary of market research, a detailed analysis of competitors (e.g., identification of competitors, their strengths and weaknesses, etc.), an analysis of the proposed business (e.g., identification and analysis of the proposed business’s strengths and weaknesses), projections of future sales, and proposed strategies relating to the business’s marketing mix (development of strategies relating to pricing, promotion, place, and positioning of the proposed product).

The financing segment of the business plan will provide a complete and detailed look at financial resources the business will require (based on the assumptions and analyses performed in other sections of the business plan and the feasibility study), including owner-supplied funds and borrowing needs. This section should include pro forma financial statements, including income statements, cash flow (budget or forecast), and balance sheets. For existing companies, realized company financials can be included in this section.

The management section will help outline the business’s management structure and strategy as it relates to the business. This section should identify key managers within the company and include a description of how each of these key individuals will contribute to the business’s success. An organizational chart should be used to summarize different management roles and responsibilities within the business and the relationship between different business segments. The management section may also include a discussion about the legal structure of the business.

Liability Protection

Grocery stores and distribution companies generally require all food processors to carry product liability insurance. For small businesses, product liability insurance can be an attached rider under a homeowner’s policy. Check with your insurance agent or even online for the best policy coverage (minimum $1 million) and premium payment. Other types of liability protection to consider are life insurance, general business liability insurance, property loss, equipment warranties, auto insurance to cover vehicles used for business purposes, and disability insurance for employees. The type of insurance needed may also depend upon the structure of business ownership.

Facilities And Equipment

Building a certified kitchen requires considerable capital outlay and time investment to ensure that all local, state, and federal building codes are followed to create a safe food-processing facility. Most commercial food products cannot be made in a residential kitchen. A separate room or facility must be built.

Wants and needs must be clearly defined when considering a private food-processing kitchen. That pretty Mexican tile is beautiful, but it may be inappropriate for wet floors and difficult to clean. A state-of-the-art mixer with a 100-gallon bowl may be nice, but a 20-quart bowl might suffice for the first year or two of production. Consider purchasing equipment with pieces that can be adapted and changed as the company’s needs increase. Before embarking on a huge expense, consider all the options available to you, especially for a new venture.

Certified commercial facilities or incubator kitchens are available throughout New Mexico (Table 2) that provide major mid-sized equipment and can be rented by the hour. Some of these facilities have support personnel that can help with recipe development, safe food-processing procedures, and marketing and business plan development. Renting a certified, permitted church kitchen or restaurant during off hours is also an option. Many businesses start in rented facilities and then move into a private commercial food-processing facility once the business is established. Avoiding a large investment in facilities and equipment—and the fixed debt payments that follow—is a major step in managing risks and rewards during the startup phase of a small business.

|

Table 2. New Mexico Food Business Incubators (current as of 09/2021) |

||

|

Name |

Address |

Contact information |

|

Northern New Mexico Community College ¡Sostenga! Commercial Kitchen |

921 N. Paseo De Oñate Española, NM 87532 |

505-753-8952 | Jan Matteson, janmatteson@nnmc.edu | http://nnmc.edu |

|

NMSU Extension Food Technology Lab |

Tejada Building, Lab Room 105 P.O. Box 30003, MSC 3AE Las Cruces, NM 88003 |

575-646-1179 | Nancy Flores, naflores@nmsu.edu | https://aces.nmsu.edu/ces/foodtech/index.html |

|

Socorro County Commercial Kitchen |

407 Center St. Socorro, NM 87801 |

505-507-0991 | Al Smoake, aandjfamilyfarm@yahoo.com |

|

South Valley Economic Development Center |

318 Isleta Blvd. Albuquerque, NM 87105 |

505-877-0373 | timn@rgcdc.org | http://www.svedc.org/ |

|

Taos County Economic Development Corporation Food Center |

P.O. Box 1389 1021 Salazar Rd. Taos, NM 87571 |

575-758-8731 | tcedc@tcedc.org | https://www.tcedc.org/programs/taos-food-center/ |

Tax Identification

In addition to obtaining a permit to operate a food-processing facility, each business must have a tax identification number from the New Mexico Taxation and Revenue Department. A business license may also be needed depending on the town and county location of the processing facility. For more information, visit https://www.tax.newmexico.gov/businesses/who-must-register-a-business/.

Starting A Food Business Checklist

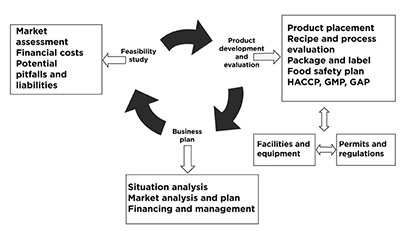

The following checklist can help you keep track of various requirements as you plan your food business. Figure 1 provides a visual diagram of the planning and development process.

Figure 1. Diagram of planning and development processes of starting a food-processing business.

Business planning and management

- Feasibility study

- Business plan

- Situation analysis

- Market analysis and plan

- Financing and management

- Tax identification number

Liability insurance protection

- Product liability insurance

- Business liability insurance

- Employee disability insurance

- Life insurance

Making a food product

- Product placement in market: refrigerated, frozen, or shelf-stable

- Recipe or formulation evaluation

- Process evaluation

- Packaging and labeling

Facilities and equipment: Private, contract packager, or kitchen incubator

- Permitted facility

- Local, state, federal building codes followed

- Equipment maintained and working

Managing food safety

Permits and regulations

- Local, state, federal applications

- Bioterrorism Act: registration, recordkeeping, prior notice

- Food processing permit: operational plan, label approval

Food safety plans

- Hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP) for meat, juice, catfish products

- Good manufacturing practices (GMPs) for food manufacturers

- Good agricultural practices (GAPs) for food producers (growers)

- Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA; see Table 2 in Guide E-510C)

- Food handlers, food mangers for homemade food processors

- Food defense

Where To Go For Additional Help

FDA—How to Start a Food Business

The primary focus of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a regulatory agency is food safety, so it does not offer financing or business tips for starting and maintaining a business. However, FDA offers information on food safety guidelines and regulations it has established that are required for informative labeling and the safe preparation, manufacture, and distribution of food products. This information can be found on their How to Start a Food Business website at http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Industry/ucm322302.htm.

References

Barton, D. 1989. What is a cooperative? In D. Cobia (Ed.), Cooperatives in agriculture (pp. 1–20). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bielik, M. n.d. New generation cooperatives on the Northern Plains [Online]. https://umanitoba.ca/faculties/afs/dept/agribusiness/media/pdf/ARDI_PDF.pdf

Reilly, M.D., and N.L. Millikin. 1996. Starting a small business: The feasibility analysis [Publication MT 9510]. Bozeman: Montana State University Extension.

U.S. Small Business Administration. n.d. Choose a business structure [Online]. https://www.sba.gov/business-guide/launch-your-business/choose-business-structure

For Further Reading

E-510B: Starting a Food Business in New Mexico: Food Processing

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_e/E510B/index.html

E-510C: Starting a Food Business in New Mexico: Food Safety

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_e/E510C/index.html

E-325: How to Submit a Commercial Food Product for Process Review

https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_e/E325/index.html

Nancy Flores is the Extension Food Technology Specialist in the Department of Extension Family and Consumer Sciences at NMSU. She earned her B.S. at NMSU, M.S. at the University of Missouri, and Ph.D. at Kansas State. Her Extension activities focus on food safety, food processing, and food technology.

Jay Lillywhite is a professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business at New Mexico State University. He earned his Ph.D. in agricultural economics from Purdue University. His research addresses agribusiness marketing challenges and opportunities.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agriculture and Home Economics on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

September 2022 Las Cruces, NM