Circular 589

James D. Libbin, Professor

Jerry M. Hawkes, Assistant Professor

Ashley Cline, Graduate Research Assistant

College of Agriculture, Consumer and Environmental Sciences New Mexico State University

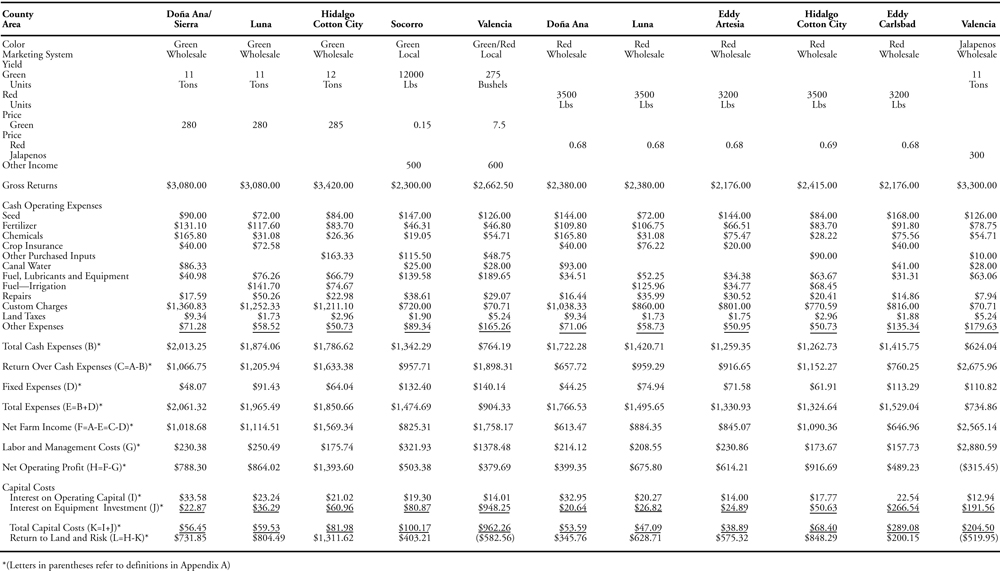

Long-term, continued success of New Mexico’s commercial chile crop depends upon the crop’s profitability in any or all of its various forms. Table 1 presents typical costs and returns of producing chile in New Mexico’s primary producing areas. These estimates provide comparisons that can be used by current and prospective chile producers and processors to assess chile production profitability.

Table 1. Costs and returns for producing chile in New Mexico, 2003.

Chile is widely recognized throughout New Mexico and the Southwest as a diverse commodity. Not only is there the obvious red versus green distinction but there also are clear differences among chile for use in farmers’ markets, roadside stands and wholesale processing. Chile is sold as fresh, canned, chopped and processed for salsa and enchilada sauce. Red chile is destined primarily for food and dye uses, ristras and whole, chopped or ground sales. Regardless of the end use, the chile crop must provide an adequate return to cover all of a producer’s costs.

Increased profit can be generated by obtaining a higher price or reducing costs. The cost-return relationship must be examined carefully by every producer of every commodity, whether in agriculture, manufacturing or even a service business. Because of the economic structure of agricultural markets, cost and return relationships are particularly important. The basic building blocks of cost and return analysis are enterprise budgets, which are later organized and compiled into other budgets, including whole farm, partial and cash flow budgets. An enterprise budget comprises all costs and returns associated with producing an enterprise in some particular manner. Enterprise budgets are constructed on a per-unit basis, such as per acre, to make a viable comparison of alternative enterprises. An enterprise is any activity that results in a product used on the farm or sold in the market, and a farm may be considered as one or many enterprises. Each enterprise requires a certain combination of resources, such as land, labor, machinery, capital and purchased inputs.

Enterprise budgets can estimate costs and returns on enterprises currently in the farm plan, as well as new enterprises under consideration. Most enterprise budgets also list physical resources necessary for production, which are useful for prospective new producers of a commodity. In addition to producers, many other professionals in agriculture find enterprise budgets valuable information sources. These include lenders, assessors and appraisers, consultants and lawyers. New Mexico State University’s Cooperative Extension Service publishes representative budgets for various regions of the state annually. These enterprise budgets represent typical costs and returns for a given size and production method in a particular region of the state. The budgets are not averages, but represent typical situations.

NMSU budgets represent current conditions for farming situations where management is above average. Adjusting these budgets for prices and yields expected in the future would increase their value as decision-making tools. Projections based upon the unique set of conditions on each farm would be most valuable. Some items can be modified easily to build more personalized budgets. Quantities and prices of purchased inputs, yields of crops, fuel costs and labor costs may be readily adapted to individual farms. Another example of a budget modification is to analyze each operation performed on each crop. If these operations are performed in a different pattern, the budgets should be changed. Crop yields and prices are highly variable from year to year. In analyzing historical budgets for use in planning, the astute manager will decide how much risk can be adsorbed and select cropping patterns accordingly. In planning, the manager should consider both optimistic and pessimistic price and yield combinations to account for risk and alternative crop rotation plans.

The effect of various costs on planning decisions and business analysis is very important. These estimates present a full cost approach to enterprise analysis. Many of the costs are opportunity costs. That is, they are the real costs of doing business but may not be cash expenditures. For example, if all labor is provided by the operator, then the entire amount listed in these estimates is money that can be kept by the operator; it represents a return to operator and family labor. Similarly, all land and all capital is charged at competitive rates, regardless of whether land is rented or owned or capital is borrowed or owned.

The key to interpreting the bottom-line figure calculated in these estimates lies in the type of decision at hand. For next year’s crop, the important point is the level of gross margins, the returns minus all cash expenses. Can enough cash be generated to meet reasonable family living needs and to cover all financial debt commitments? In the long run, all expenses must be covered, which is particularly important when trying to determine whether to buy a farm. In the short run, a negative net income is not desirable, but it may not necessarily cause business failure. For a short time, depreciation and other noncash costs can provide a cushion to get over the hump.

Budgets like these are updated annually. More detailed estimates may be obtained from local Extension agents.

Appendix A

Depreciation expense: Annual allowance for the deterioration of an asset that has a productive life of more than one year. Depreciation is not paid in cash, but it is an expense to the business, since the purchase price of a long-lived asset cannot and should not be deducted in any one year.

Enterprise budget: A detailed, full-cost list of all returns and costs (whether paid or unpaid) associated with a particular crop or livestock enterprise.

Fixed costs: Expenses that do not vary with the level of production, such as depreciation and personal property taxes. For example, personal property taxes are the same for a tractor, regardless of whether that tractor is used on one or 300 acres. (Line E)

Gross returns: Total cash receipts from a crop, i.e. total yield times price. (Line A)

Interest on operating capital and equipment investment: A calculated cost, or opportunity cost, on the use of capital in the farm business. For some farmers, interest cost might be an outlay cost, while for others it might be an imputed cost. (Lines I and J)

Net farm income: Returns to labor management, capital, land and risk, i.e. gross returns minus purchased inputs, fuel, oil, lubricants, repairs and fixed costs. (Line F)

Net operating profit: Gross returns minus total operating expenses. (Line H)

Operating capital: Operating expenses minus fixed costs, i.e. the amount of cash required for all purchased inputs (including labor, fuel, oil and repairs) to produce a crop, without regard to machinery, equipment and land investments.

Operating expenses: The total of all costs of producing a crop, except interest.

Opportunity cost: The cost using a resource in one enterprise when it could be used in alternative enterprises or investment opportunities measured by the return that could be obtained from using the recourse in an alternative investment. For example, if cash used in crop production could be placed in the bank at a 10 percent rate of interest, the opportunity cost of cash to the crop would be 10 percent.

Overhead expenses: Expenses not directly associated with production, such as insurance, employee benefits, land taxes and utilities. These costs occur without regard to level of production or whether production exits at all.

Partial budgeting: A planning procedure that lists only receipts and expenses that are affected by a particular change in procedure or organization.

Rate of return on investment: Net operating profit divided by the total machinery, equipment and land investment. A measure of asset profitability in percentage terms.

Return over cash expense: Gross returns less all cash operating expenses. (Line C = A−B)

Return to land and risk: Net operating profit minus the interest change on the use of machinery, equipment and operating capital. This return figure shows the final return before a land charge is calculated. (Line L)

Return to risk: Return to land and risk minus a charge for land investment; the amount of gross returns left over after charges are made for every production factor.

Variable cost: Expenses that vary with the level of production, such as labor, fuel, oil and repairs, fertilizer and seed.

Gross margins: Returns minus variable costs; the most important short-run planning figure.

Return to capital, labor, land and risk: Charges for the listed factors of capital, labor and land have not yet been subtracted from gross returns. Typically, these three factors are owned.

Whole-farm budget: Projected crop mix revenues and expenses for a production year. A projected plan and income statement.

To find more resources for your business, home, or family, visit the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences on the World Wide Web at pubs.nmsu.edu.

Contents of publications may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved. For permission to use publications for other purposes, contact pubs@nmsu.edu or the authors listed on the publication.

New Mexico State University is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer and educator. NMSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating.

Printed and electronically distributed September 2003, Las Cruces, NM.